Family trims care home costs by more than £1,000 a month as fees soar

NHS funding schemes and local authority rules offer relief but remain opaque for families navigating hundreds of thousands in fees

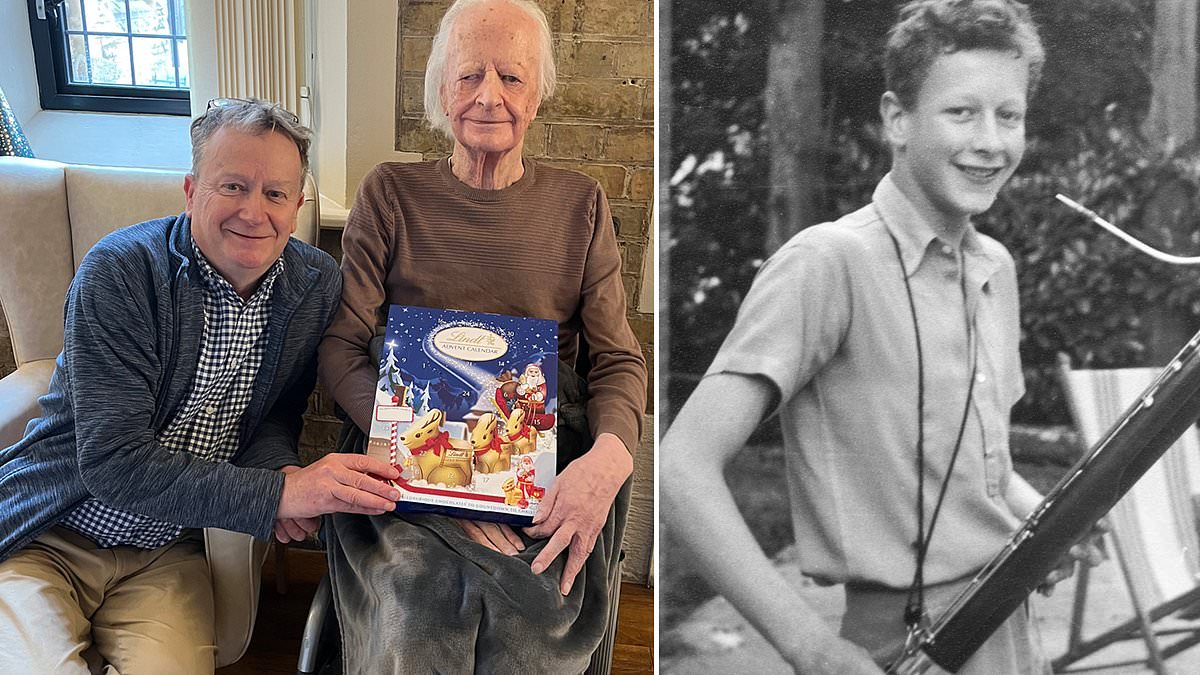

A UK family slashed more than £1,000 a month from their relative’s care bill by moving him from a nursing home to a residential facility, after years of mounting charges that have drained tens of thousands from the family purse. The case underscores how rapidly care costs can outpace income and highlights the mixed landscape of government funding and local authority support that families must navigate when a loved one needs long-term care.

Richard, who suffered a catastrophic stroke in his 50s and is cared for by his nephew, has been under a deputy’s management since 2013. In 2013, his care home fees totaled £32,902. His latest annual bill rose to £74,291, reflecting a trajectory that has seen more than £500,000 in fees paid over 12 years. Richard’s parents had shouldered the duties of managing his finances for roughly two decades before that, meaning the family’s cumulative care expenditures approached the £1 million mark. While Richard’s extended need is not representative of the typical care recipient, the story illuminates how quickly costs can accumulate even for someone with substantial private resources and pensions.

There are several routes families can pursue to offset costs, though access to them is often opaque and uneven. Continuing Healthcare funding, or CHC, is provided by the NHS and can cover all or part of care home fees, or the care costs for those living at home. Crucially, CHC is not means tested, and it is designed for people with significant ongoing physical or mental health needs. However, rules are intricate and, in many cases, outcomes are disappointing: 83% of CHC claims are rejected, according to a healthcare think-tank analysis cited by care advocates. For those who are rejected, an appeal can be made to the local Integrated Care Board within six months of the decision.

Two key points help families understand CHC. First, eligibility depends on the level of care needed, not the specific illness that caused the person to enter a care setting. Second, families should not rely on a care home to drive the CHC application, as homes have a financial incentive to obtain funding from private sources rather than NHS funding, which can reduce beds’ revenue depending on funding structure.

Other potential sources of help include Funded Nursing Care (FNC), which is paid directly to nursing homes by the local Clinical Commissioning Group. FNC can be available if a resident does not qualify for CHC but lives in a home registered to provide nursing care. In many cases, FNC amounts amounted to roughly £1,000 per month for the resident, varying by location and the home’s classification. When Richard moved to a residential home, he no longer qualified for FNC, a shift that further altered the cost balance. The FNC structure means the amount can range from a standard weekly rate of about £254 to £349, depending on local factors.

Disability Living Allowance (DLA) provided an additional lifeline for Richard, with a monthly total of £558 noted by his family. The DLA system differentiates between care, which helps with daily activities, and mobility. The DLA program has been phased out for new applicants and is being replaced by Personal Independence Payment (PIP) for those under the state retirement age and Attendance Allowance for those over retirement age. Richard’s DLA also mattered because it could be claimed even if funds were not strictly earmarked for the care home, providing an important buffer against monthly costs. Attendance Allowance offers two weekly rates, and is not means tested nor taxable.

Another potential source of support is the Disability Living Allowance’s successor framework, and local authority funding remains an option for those who have exhausted other avenues. Local authorities, however, require means testing and set capital thresholds—around £23,250 in England or £50,000 in Wales. Deliberately reducing assets to meet these thresholds, a practice known as deprivation of assets, can lead to a local authority denying funding and forcing the individual to pay for care themselves. If funding is approved, some families must accept a move to a cheaper home, or may be able to top up funding to stay in a preferred facility; conversely, receiving local authority support can affect eligibility for other benefits, including a portion of the state pension, which could be diverted to cover care costs.

The practical effect of these policies is stark in Richard’s case: the family faced a January 1, 2025, fee hike that would push monthly costs toward £7,500 in the nursing setting. After consultation with relatives, they relocated Richard to a residential home with substantially lower ongoing fees. The result has saved more than £1,000 each month, though the move does carry trade-offs, including changes to the long-term funding mix and the potential for requalification processes if care needs evolve.

The experience reflects broader market dynamics in the business of elder care: costs are rising faster than incomes and pensioners’ savings, while public funding options — even when available — are complicated, inconsistent in practice, and often difficult to secure. Rachel Hutchings, a researcher at the Nuffield Trust, notes that access to CHC funding is unfair and inconsistent, a sentiment echoed by families navigating eligibility and appeals. Supporters urge families to pursue multiple avenues and to seek professional advice when applying for CHC, FNC, or other benefits, and to be wary of relying on a care home to drive funding decisions.

For families facing similar decisions, a careful review of benefits, allowances, and local authority options is essential, along with considerations of how changes in funding might affect pension entitlements and daily living arrangements. While Richard’s family found relief by changing the level of care and the setting, the path remains complex and fraught with policy-related uncertainties that affect tens of thousands of households across the country.

The broader question remains how to ensure that care remains dignified and financially sustainable as the population ages. As costs continue to mount, families and policymakers alike will need to balance eligibility criteria, safeguarding against deprivation, and the realities of long-term care funding to prevent similar financial shocks in households across the country.

If you want to explore funding options further or share your experience with care home costs, resources are available through NHS CHC guidance, local authority social services, and disability and pension programs, though eligibility and application processes vary regionally.