Alps could face peak glacier extinction by 2033, study warns

New projections warn thousands of Alpine glaciers could vanish this century as warming accelerates, threatening winter tourism and freshwater systems.

The European Alps could reach a point of peak glacier extinction as early as 2033, according to a new study published in Nature Climate Change. Using three state‑of‑the‑art global glacier models and several climate scenarios, the research team projected how many glaciers in ski destinations worldwide may remain by 2100. Under a 1.5°C warming above pre-industrial levels, only about 430 glaciers would remain in the European Alps from today’s roughly 3,000; at 2.7°C warming, about 110 would remain; and under a 4°C warming, roughly 20 glaciers would survive. Lead author Lander Van Tricht of ETH Zurich called the findings a stark warning about the pace of glacier loss.

Regions with many small glaciers at lower elevations or near the equator are especially vulnerable. The Alps and similar zones could see more than half of their glaciers vanish within the next 10 to 20 years, the study said. The researchers note that even mid‑sized Alpine glaciers such as the Rhône would shrink to tiny remnants or disappear entirely under higher warming. The team warned that melting glaciers can have implications for tourism, since many ski resorts rely on glaciers for reliable snow and extended seasons. "When a glacier disappears completely, it can severely impact tourism in a valley," Van Tricht said.

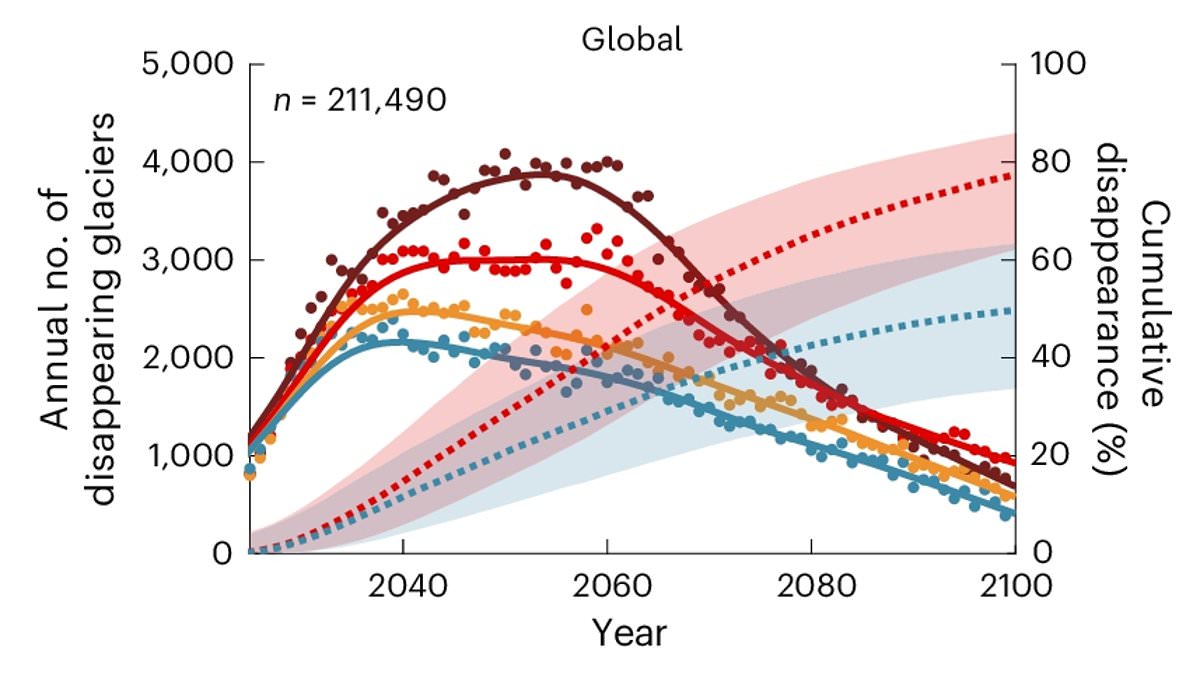

In the most extreme warming scenario, the largest glacier in the Alps, the Aletsch Glacier, would fragment into several smaller ice masses. The projections also suggest that the world could hit a peak glacier extinction—where annual glacier loss reaches its maximum—earlier than previously thought. The authors noted that many glacier areas are concentrated in tourism‑dependent regions, making the economic impact of glacier loss particularly acute for valley towns and winter sports economies.

Globally, no region appears exempt from glacier decline. In the Rocky Mountains, about 75% of today’s glaciers could be lost under a 1.5°C warming; in the Andes and Central Asia, more than half could disappear. Even in the Karakoram, where some glaciers briefly advanced in the early 2000s, the study projects substantial retreat. The researchers stressed that the results underscore the urgency of ambitious climate action to limit warming.

A separate study published last year by researchers at the University of Bayreuth found that one in eight major ski sites could have no days of snow cover by 2071–2100 under a high‑emissions pathway, underscoring risks to winter tourism beyond the Alps and highlighting the global economic stakes of glacier loss.

The Paris Agreement, signed in 2015, aims to keep global warming well below 2°C and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. The new Alpine projections add to the body of evidence that reaching the 1.5°C goal could significantly reduce glacier loss in many regions, preserving some high‑elevation snow cover that supports ski industries, ecosystems, and water resources. The study notes that while many glaciers will shrink this century, some could persist longer if warming is limited, reinforcing the critical choices facing policymakers and industry as they plan for a warmer, less glacier‑dependent future.