America’s flood-insurance system is sinking as floods rise and costs mount

As flood damages mount and the NFIP sinks deeper in debt, lawmakers, homeowners and insurers face a reckoning over risk, pricing and who pays to protect communities.

America’s flood insurance program is sinking as widespread flooding intensifies this year. The National Flood Insurance Program, which underwrites residential flood losses, has faced a string of costly flood events. The July 4 weekend in Central Texas brought at least 135 fatalities and estimated damages topping $22 billion, according to one estimate. Earlier this year the NFIP borrowed $2 billion from the U.S. Treasury to cover 2024 storm claims, and total debt has risen to more than $22.5 billion as claims continue to be processed. With homeowners trying to rebuild, rising costs and slow service are adding to the stress in communities along rivers, coasts, and floodplains.

NFIP today covers about 4.7 million policyholders with roughly $1.3 trillion in flood protection. The program, founded in 1968, was designed because private insurers largely avoided flood risk. It is funded through short-term Congressional authorizations and is authorized through September 30, 2025. The program is tasked with providing access to affordable flood coverage while remaining financially solvent, a balance that has proven difficult as risk rises. Economists describe the tension as a moral hazard because subsidized pricing can encourage people to stay in high-risk areas rather than relocate or invest in mitigation.

Homeowners like Sharon Cozort in Houston illustrate the tradeoffs. She bought her home in 2006 after learning the property lay within a floodplain and carried NFIP coverage for about 25 years. After Hurricane Harvey in 2017, which flooded the area for days, she chose to rebuild with the help of the federal policy, given the costs. Now she says the risk remains and believes her house will flood again, noting that the broader community faces growing costs and rising insurance prices that complicate returns or relocations. Plans to extract equity from the home to fund retirement are shaped by the availability of government insurance and the fear of another major flood.

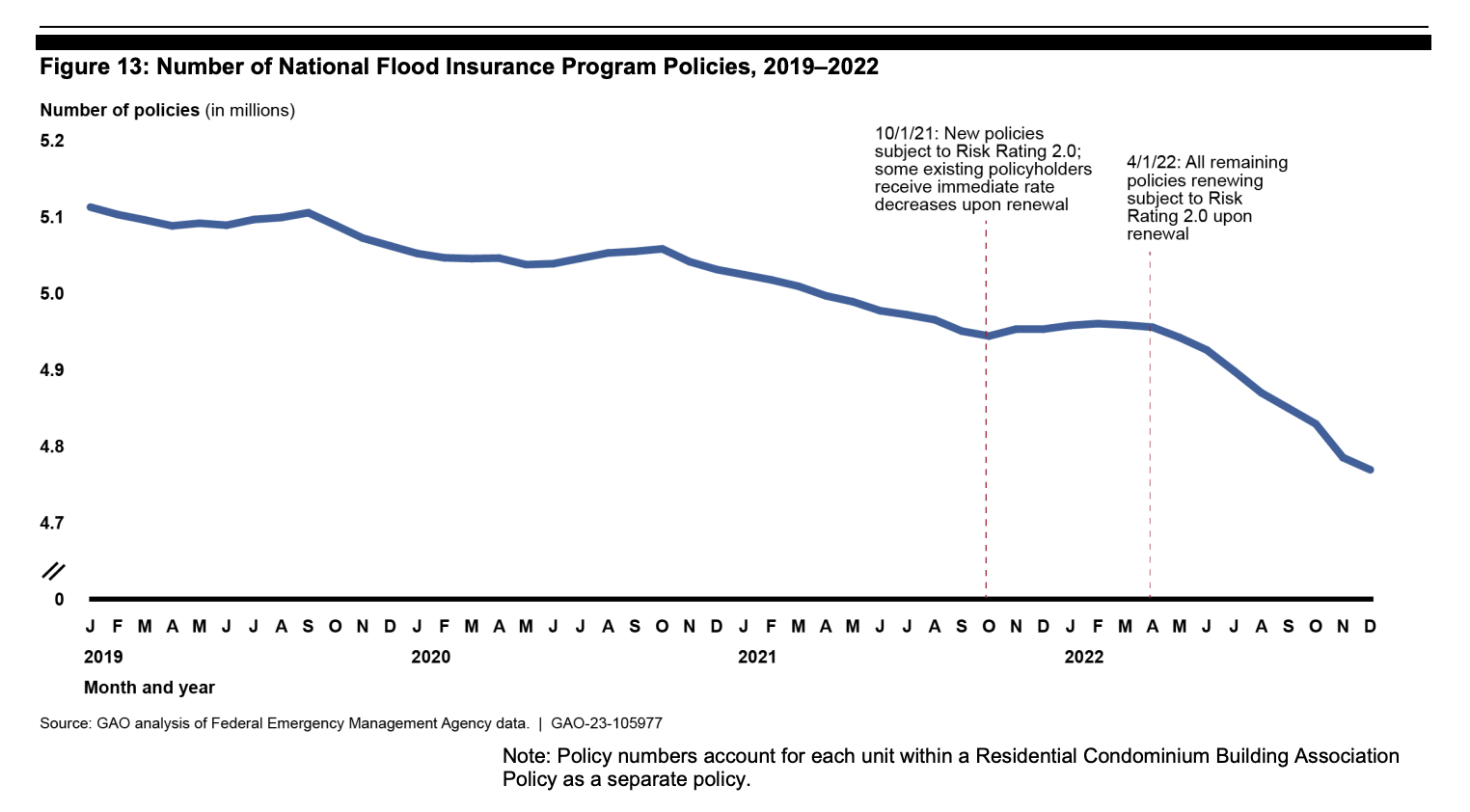

Flooding is the most frequent and costly disaster in the United States, and climate change is reshaping risk. More Americans now live in flood-prone areas even as property values rise and construction costs climb. The Environmental Defense Fund estimates that the baseline level of flood risk is increasing, driven by sea-level rise and heavier rainfall. The federal program relies on a 100-year flood zone as a benchmark, but climate change is shifting risk so that the zone is moving and expanding in places. In 2022, NFIP implemented Risk Rating 2.0, the agency’s biggest update since its founding, which aligned premiums more closely with actual risk but also boosted costs for many homeowners, prompting some to drop coverage. Experts warn that even Risk Rating 2.0 may still mismeasure risk in places where flooding is already occurring more frequently than maps suggest.

Mapping and pricing are central to the program’s challenges. Private insurers largely exited flood coverage because damages are highly correlated across properties, making losses unpredictable. The pool of insured properties is skewed toward higher-risk homes, complicating the program’s ability to collect enough premiums. Analysts note that even with Risk Rating 2.0, more properties are in high-risk zones than official maps indicate, and some homes outside designated zones still flood. At the same time, premiums under NFIP are often subsidized, muting price signals that would encourage relocation or mitigation. In some analyses, subsidized pricing has appeared to draw more people to flood-prone locations because the coverage seems affordable. The result is a mismatch between risk and coverage that keeps losses off private balance sheets and onto taxpayers.

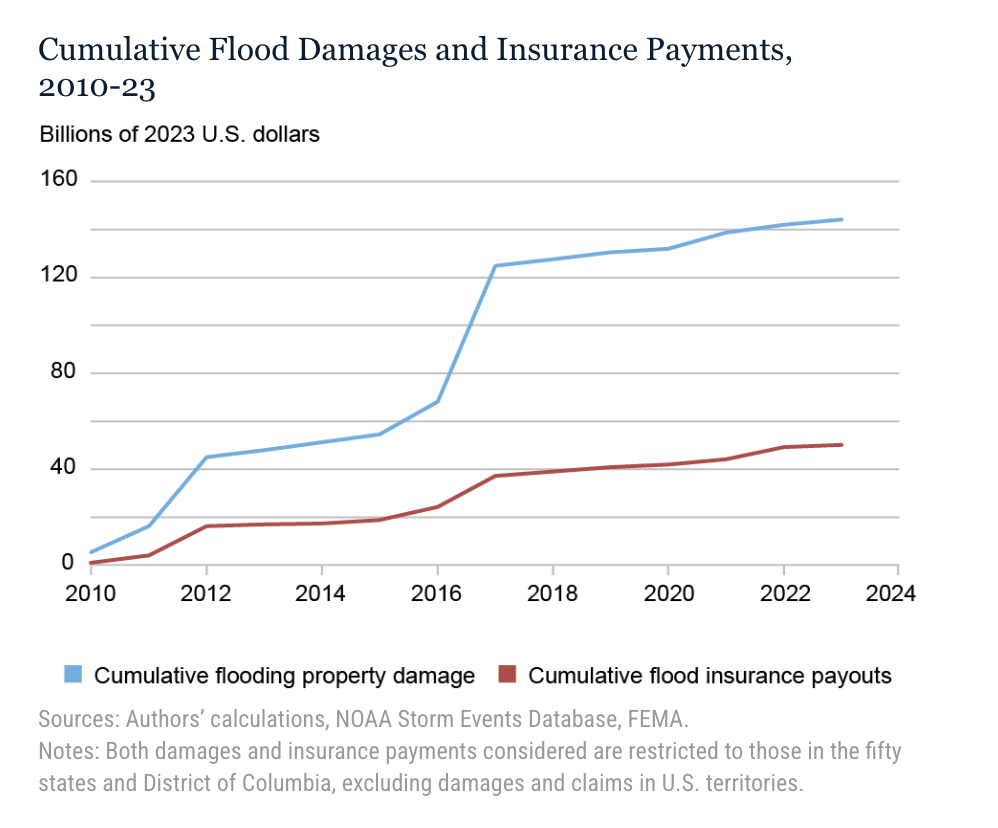

The program’s challenges extend beyond maps and premiums. The Environmental Defense Fund has urged restoring grant programs that fund watershed restoration, levees and other flood protections, and lawmakers have called for greater federal, state, and local investment in adaptation. A Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia working paper estimated that 70 percent of flood losses are uninsured, totaling about $17.1 billion in 2024, underscoring the limits of insurance alone in protecting households and communities. Even for those with coverage, rising premiums and lapses mean the total cost of flood losses continues to outpace insured losses, and renters often remain underprotected. Some analysts question whether NFIP will ever operate as a true risk-based insurance system, given political and budgetary constraints.

Looking ahead, many experts argue for a fundamental rethink of how the country approaches flood risk. Some call for sharper policies to discourage new development in floodplains and to relocate residents over time, arguing that the social cost of continuing to build in risky areas exceeds the benefits. Others urge a more robust public program that treats NFIP as a public service rather than a profit centre, accepting that losses will exceed receipts and that the program requires ongoing congressional support and reform. Critics note that political pressures from state and local governments, particularly in places with low taxes and high property values along coastlines or rivers, complicate decisions to curb growth in flood-prone areas. As one expert puts it, the challenge is political as much as technical: to move people out of high-risk areas gradually over decades, while expanding resilient infrastructure and risk-aware redevelopment.

At the federal level, the path forward remains unsettled. FEMA’s future role has been debated, including calls to restructure the agency or reorganize flood programs, and discussions about whether to keep NFIP within FEMA or to reframe it as a broader disaster insurance or resilience program. For now, the program remains authorized but financially strained, with claims costs rising and the gap between premiums and expected losses growing as climate hazards intensify. States and localities face pressure from taxpayers and developers alike to maintain housing growth in valuable markets while absorbing the cost of flood risk. The result is a looming political reckoning that will shape where Americans live, how they rebuild, and who pays for flood risk in the years ahead. The country can no longer rely on a largely additive fix; it will have to confront fundamental questions about how to manage flood risk in a changing climate. The trend line is clear: flood losses are rising, and the NFIP’s balance sheet will likely grow more negative unless reforms align risk, pricing, and policy goals. The system may become a drain on public resources or a blueprint for a broader, more proactive approach to living with water. The crisis is not just a technical problem for insurers but a societal one that will demand a long, deliberate policy response. Until then, the flood insurance program’s head above water status will continue to deteriorate as flood events complicate recovery nationwide.

Experts emphasize that risk management must extend beyond insurance. Restoring or expanding grants for flood-control projects, updating flood maps to reflect evolving risk, and investing in land-use reform are among the steps many researchers say are needed. As policymakers juggle the budget, the climate signal is undeniable: communities in flood-prone areas will face higher costs, more frequent evacuations, and greater disruption to daily life unless risk is addressed on multiple fronts.

In the end, public officials and private insurers alike acknowledge the central dilemma: if NFIP prices risk to reflect reality, many homeowners may be priced out of coverage; if they keep subsidies, the program remains fiscally fragile and may fail to deter risky development. The debate now turns to a practical mix of risk-based pricing, robust resilience investments, and smarter land-use policy that can reduce exposure over decades. States and localities must also weigh incentives that currently push development in high-risk areas, particularly where tax structures or revenue streams promote continued growth in waterfront or river-adjacent parcels. The coming years will test whether the United States can align its flood financing with a changing climate or whether NFIP will continue to struggle under the weight of escalating losses and political constraints. The era of flood risk that mirrors pre-2010s maps is ending; the policy question is whether the country will build a new framework for a flood-prone future.

In the near term, the system remains under pressure, and the next renewal decision for NFIP will occur as new flood risks emerge and rebuilding costs rise. The outcome will affect millions of homeowners, renters, lenders, and communities that rely on the program to finance protection and recovery after floods. The question is not only how much the country is willing to spend, but how it wants to live with water in a warming world. The path forward will require difficult choices about risk, price, and place—and a long‑term commitment to resilience that goes beyond the walls of any single insurance program.