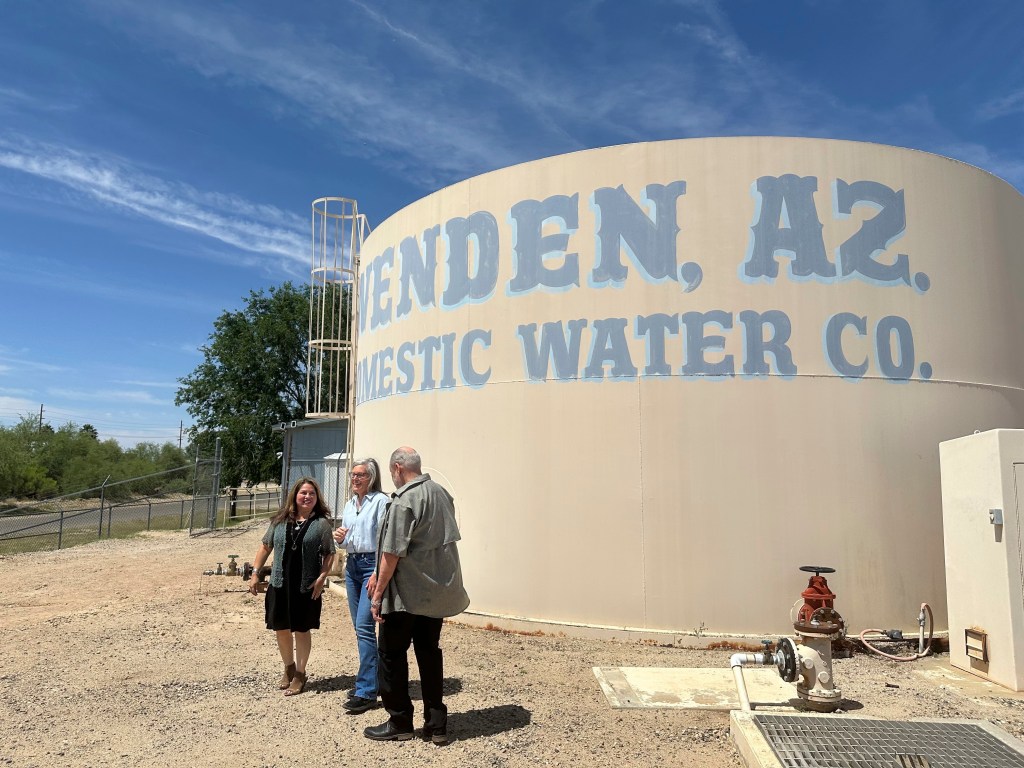

Arizona town of Wenden is sinking as unregulated groundwater pumping accelerates, study and lawsuit say

Residents and officials warn of continued subsidence as megafarms expand and state regulators struggle to curb groundwater extraction

Wenden, an unincorporated community in western Arizona, has sunk more than 18 feet over roughly eight decades and continues to drop at rates approaching 3 inches a year as residents and officials struggle to reach groundwater, according to local authorities and recent research.

Locals say residents have had to drill progressively deeper wells, in some cases thousands of feet, to find potable water as the water table falls. Gary Saiter, head of the Wenden Water Improvement District, described the decline as "a train wreck waiting to happen," saying the community sank more than 3.5 feet in the last 15 years and is subsiding at roughly 2.2 inches per year.

An Arizona State University study released this year linked the rapid acceleration of groundwater use across the Colorado River Basin to land subsidence in parts of Arizona. Jay Famiglietti, the ASU hydrologist who led the study, said compaction of clay-rich soils is a key mechanism: when water that separates flat clay minerals is pumped away, the layers settle and the land surface drops.

Wenden's water system draws a portion of its supply from the Colorado River — officials estimate roughly 38% of the community's water comes from that source — the same river tapped by major cities across the Southwest. But local officials say large agricultural operations, including foreign-owned megafarms that expanded rapidly during the 2010s, are pumping large volumes of groundwater in the region and accelerating the decline.

State regulators and the Arizona attorney general have begun to scrutinize those operations. Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes filed a nuisance lawsuit accusing Fondomonte, a farm owned by Almarai, Saudi Arabia's largest dairy company, of inflicting harm on Wenden through excessive groundwater extraction. Mayes' office estimates the company accounts for about 81% of groundwater use in the area the complaint targets. Fondomonte responded that its water use is reasonable and that it makes a "conscious effort to manage water use."

During the 2010s, U.S. Department of Agriculture data show foreign-owned megafarms increased their holdings in the Southwest from roughly 1.25 million acres to nearly 3 million acres, a shift that local water managers and some state officials say has altered groundwater dynamics in vulnerable basins.

The ASU study also noted that nearly 80% of Arizona lacks comprehensive regulations for groundwater pumping, which means many large agricultural users are not required to report volumes they extract. That regulatory gap has raised concerns among rural communities that their wells are being affected by extraction they cannot track or control.

Local leaders say the combination of deepening wells, lack of reporting requirements, and the ability of distant buyers to purchase water or land rights has left towns such as Wenden with few options. "The water has disappeared for them because the Saudis are sucking it out of the ground," Saiter told reporters, echoing complaints that have spurred legal and political action across the state.

Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs proposed creating rural groundwater management areas during the 2025 legislative session to give local authorities more tools to control pumping. Lawmakers, however, were unable to agree on specific limits or a compromise measure. Debate centered on how aggressively to cut pumping from aquifers and which entities and areas should be subject to new rules.

State officials, academics and local water managers say the situation in Wenden illustrates broader tensions in the Colorado River Basin, where demand from cities, agriculture and industry has strained supplies already reduced by prolonged drought and climate-driven changes in runoff. The ASU study places local subsidence in the context of basin-wide groundwater depletion and warns that continued extraction could deepen impacts.

For now, Wenden residents continue to adapt by investing in deeper wells and water infrastructure, even as legal and political processes play out. The attorney general's lawsuit represents one of the more prominent legal efforts to hold a single farm accountable for regional groundwater impacts; the outcome could influence how other states and communities approach disputes over groundwater and large-scale agricultural water use.

Researchers and officials say longer-term solutions will require coordinated management of surface and groundwater, improved reporting of extractions, and policies that address the distributional effects of large-scale agricultural purchases and pumping. In the absence of statewide regulation for much of Arizona's subsurface water, communities like Wenden are confronting the immediate consequences of declining aquifers while policymakers weigh regulatory and legal avenues to slow or reverse the trends.