Atlantic Hurricane Season Remains Unusually Quiet During Peak Period

No named storms have formed in nearly three weeks amid wind shear, dry air and reduced African rainfall, meteorologists say

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico — Not a single named storm has formed in the Atlantic in nearly three weeks even as the basin moves through the climatological peak of hurricane season, meteorologists said, a lull only rarely seen in the modern record.

Tropical Storm Fernand was the last named system, forming Aug. 23 and dissipating Aug. 28 while remaining over open water. Ernesto Rodríguez, meteorologist in charge of the National Weather Service forecast office in San Juan, said the current quiet period — running roughly from Aug. 29 to Sept. 15 — is only the second time that no named storms have formed during that stretch since record-keeping began in 1950. "Usually, conditions during this period are prime," he said.

Forecasters point to three main factors suppressing tropical cyclone formation this month: stronger-than-usual vertical wind shear, persistent dry and stable air across the tropical Atlantic, and a reduction in rainfall over West Africa, where many tropical waves originate. The increased wind shear is linked to a cyclonic circulation in the mid- to upper troposphere, which disrupts the vertical organization storms require.

Philip Klotzbach, a meteorologist at Colorado State University, noted the public curiosity about the lull on social media. Researchers at Colorado State published an explanatory report this month that called the pause in activity "quite remarkable," and cited "insufficient instability" as a key limiting factor for storm formation. Michael Lowry, a hurricane specialist, wrote that the usual "conga line" of tropical waves exiting Africa — which normally peaks by late August and September — has been delayed this season.

The current slowdown contrasts with early-season activity: Hurricane Erin strengthened in August and reached Category 5 intensity while remaining well offshore. Overall, the basin has produced six named storms so far this year. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration had earlier predicted an above-normal season with 13 to 18 named storms, five to nine of which would become hurricanes and two to five of those major hurricanes with winds of 111 mph or greater.

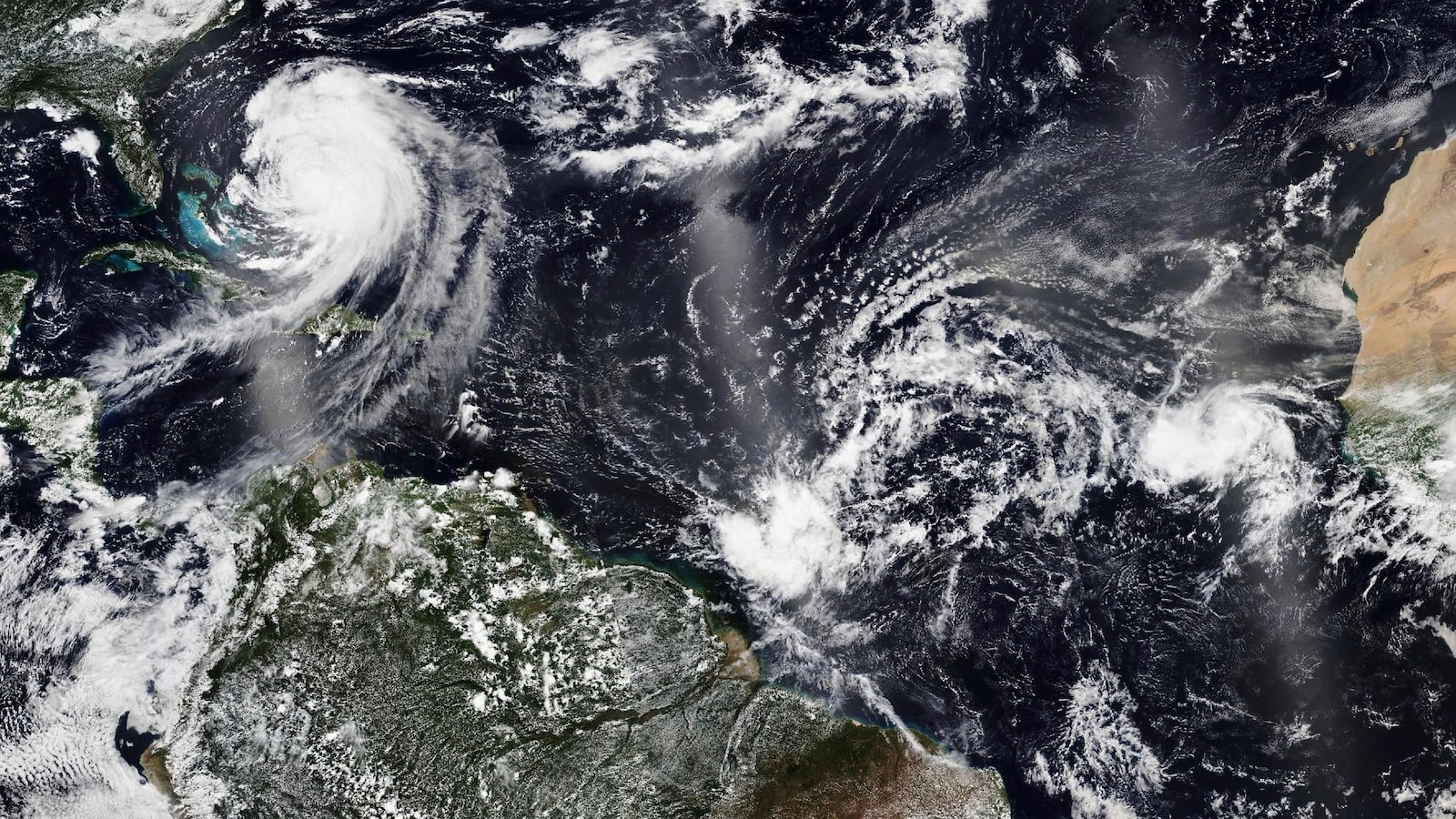

Despite the quiet spell, forecasters cautioned that the season is not over. Rodríguez said conditions could become more favorable from Sept. 15 to Oct. 15, when ocean temperatures remain warm and other factors could align to support development. Models and forecast discussions currently show a cluster of storms several hundred miles east of the Caribbean that is expected to become a named storm in coming days; that system is forecast to recurve away from land and remain over open water, though it could strengthen. A separate cluster behind it currently carries only a roughly 20% chance of formation, forecasters said.

The relative calm has provided some relief to island communities still recovering from past storms. Puerto Rico continues rebuilding from the devastation of Hurricane Maria, which struck as a powerful Category 4 on Sept. 20, 2017. "This is pretty positive, especially for us in Puerto Rico," Rodríguez said.

Historical parallels underscore the rarity of the current lull. The quietest peak period previously recorded was in 1992, immediately after Hurricane Andrew devastated parts of Florida. A typical Atlantic hurricane season, NOAA says, averages 14 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes between June 1 and Nov. 30. Forecasters remind residents and emergency managers that most activity historically occurs in August and September and that late-season swings in atmospheric patterns can quickly change the outlook.

Meteorological agencies will continue to monitor atmospheric shear, moisture availability, African rainfall trends and sea surface temperatures for signs of renewed activity. For now, the Atlantic has provided an unusual pause in storm formation during what is usually its most active interval.