Australia faces $600 billion property wipeout by 2050 as climate risks mount

National risk assessment warns rising seas, bushfires and floods could put 1.5 million Australians in harm’s way and reshape the property market, even as buyers flock to high‑risk areas

Australia’s first National Climate Risk Assessment released this week warns that rising sea levels, worsening bushfires, and more extreme weather could erase as much as A$600 billion in residential property values by 2050 and place more than 1.5 million Australians in harm’s way. The assessment outlines a landscape in which high‑risk areas face mounting physical threats and financial vulnerability, with some homes potentially becoming uninsurable in the years ahead. The findings come as buyers continue to pursue property in coastal and fire‑prone regions, raising questions about how climate risk will be priced into markets over the long term.

More than 1 million homes could fall into very high risk zones by 2050, according to the report, potentially rendering them uninsurable in parts of the country. In markets where insurers have already pulled back, homeowners could face properties that are uninsurable, unfinanceable, or difficult to sell. The assessment also signals that banks and regulators may tighten building codes and lending standards as climate threats intensify, a shift that could reshape the affordability and availability of housing in vulnerable areas. The government’s climate risk workframes a broader transition that could redraw where Australians can buy, insure, and finance homes.

Real‑estate market data compiled alongside the risk analysis shows a complex picture. Ray White analysed price growth in 85 suburbs identified in the Climate Council’s 2024 At Our Front Door report. Of the 64 suburbs with sufficient sales data, 58% recorded price growth over the past year, averaging about 5.8%. Some of the strongest growth occurred in South Australia’s Adelaide Hills, where nearly every home sits in extreme bushfire risk. Suburbs such as Stirling, Heathfield, Crafers West, and Aldgate posted annual gains of up to 12.5%, with median prices topping $1.3 million in several cases. The mix of risk and reward in these areas underscores how lifestyle and location can still drive demand even as climate threats loom in the background.

Beyond the Adelaide Hills, high‑risk coastal areas also saw notable activity. Data from a market analytics firm highlighted several local government areas with strong seller profits in the June quarter, including Kiama, Byron Shire, Cottesloe, Surf Coast, and Sydney councils such as Waverley, Northern Beaches, and Woollahra. Median profits in these areas ranged from roughly $575,000 to $758,000, illustrating a degree of resilience in premium coastal markets despite long‑term risk signals.

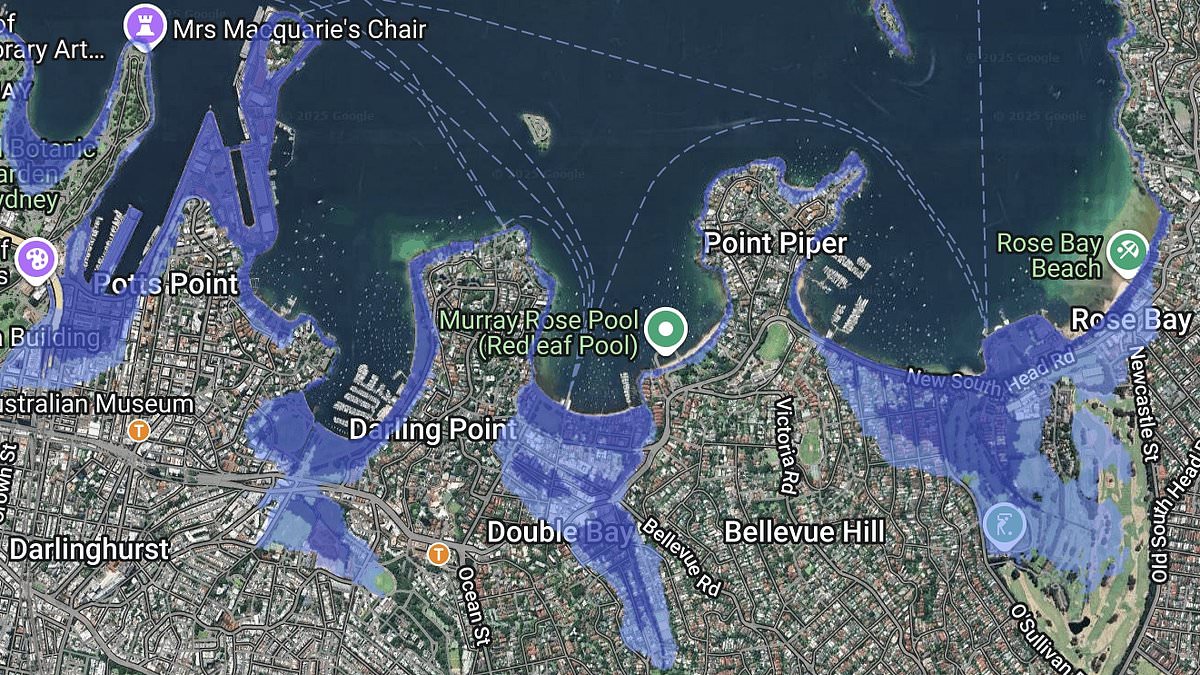

Allegra Spender, the federal MP for Wentworth, voiced concern over the report’s identification of suburbs in her electorate as particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels. She urged swift policy action to safeguard residents and strengthen planning and resilience measures as parts of Sydney’s east coast face ongoing pressure from climate threats.

The east coast pattern mirrors a national dynamic: lifestyle appeal continues to attract buyers to high‑risk towns and suburbs. In Queensland, demand remains robust in areas flagged for climate risk, including Groper Creek, Cunnamulla, and Brookstead. In Victoria, towns such as Hollands Landing, Manangatang, and Shepparton—each noted for vulnerability—continue to attract interest despite risk signals. Still, there are signs of strain. About 42% of high‑risk suburbs recorded price declines, particularly in lower‑value coastal towns and some prestige markets, suggesting that buyers are starting to factor climate threats into pricing and expectations.

Even in markets that continue to rise, the underlying costs and risks are shifting. The Climate Risk Assessment notes that more than one million homes could sit in the highest risk category by 2050, with some insurers already exiting certain markets. The report cautions that the tipping point may come as lenders, regulators, and governments respond with tighter building codes, more conservative lending, or more frequent extreme‑weather events that alter buyers’ willingness to finance high‑risk properties.

Overall, the assessment frames climate risk as a long‑term financial and social challenge for households and the property market, not a temporary anomaly. It underscores the need for proactive planning, resilient infrastructure, and policies that align housing development with evolving risk landscapes across Australia.