Biodegradable Wet Wipes Persist in Waterways for Weeks, Study Warns

Cardiff University finds 'biodegradable' wipes linger in rivers, form fatbergs, and calls for tighter labeling and testing standards

A Cardiff University study found that wet wipes marketed as biodegradable can persist in freshwater for more than five weeks, challenging their environmental claims and contributing to blockages known as fatbergs in sewer systems. Researchers tested two widely available brands—Brand A and Brand B—both labeled as biodegradable, in 10 urban rivers and streams around Cardiff over a five-week period to assess real-world degradation.

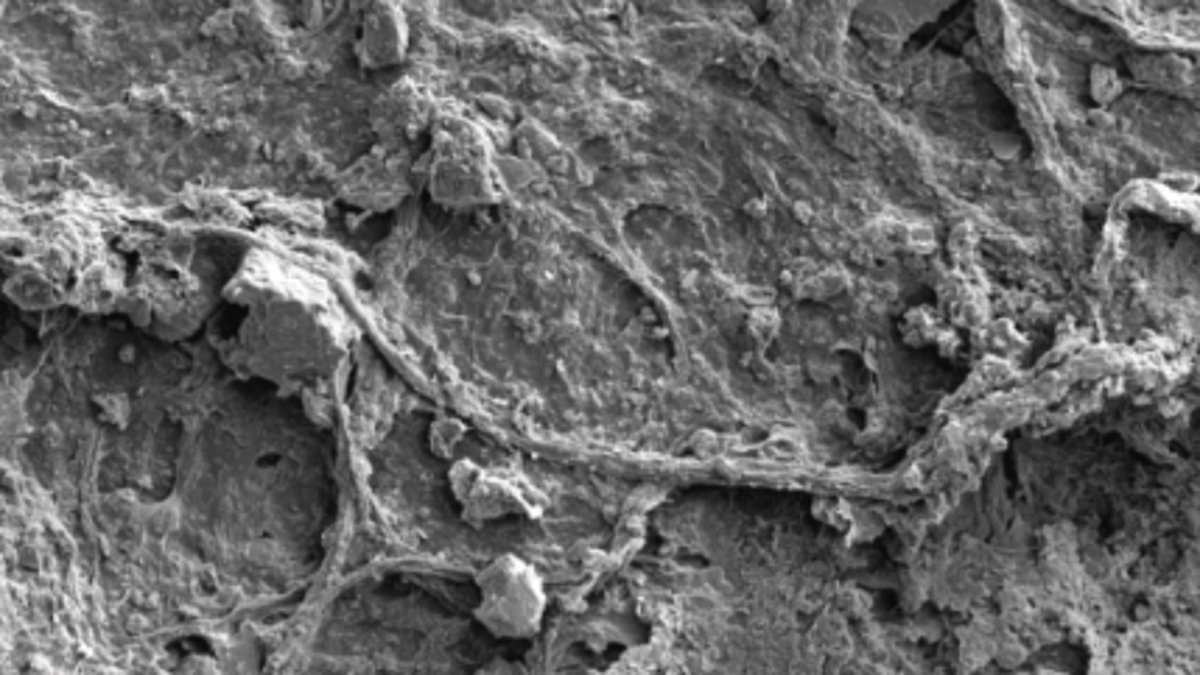

Over the study period, the wipes showed initial signs of decay but fragments remained intact well past five weeks, contradicting typical biodegradation expectations. Brand A, which contained more natural cellulose, degraded at about 6.7 percent per day, while Brand B, containing more regenerated cellulose, degraded at about 3.1 percent per day. The researchers used high-cellulose cotton strips as a comparison and tracked degradation via tensile strength, water chemistry, temperature, river-level changes and microbial activity to simulate real environmental conditions.

The real-world river environment appeared to accelerate degradation compared with laboratory tests, likely due to higher microbial activity and dynamic conditions in flowing water. Nevertheless, significant wipe fragments persisted for weeks, suggesting that lab-based biodegradability claims may not translate to freshwater settings. The study also found that the presence of river debris can coat and protect wipe particles, potentially slowing disintegration further.

Unlike standard toilet paper, wet wipes do not disintegrate as readily, and they can congeal in plumbing to form blockages that accumulate fat, oil, grease and other materials into fatbergs. These obstructions can extend for meters and take weeks or months to remove, with some fatbergs growing to enormous sizes beneath major cities. In the U.K., authorities have warned that fatbergs can threaten sewage infrastructure and may release plastics into the environment as they break apart.

Storm overflows, which are designed to discharge excess diluted sewage into rivers during heavy rainfall to prevent urban flooding, can exacerbate the problem by sending flushes of wipes and other textile fibers into waterways. When flushed items reach rivers and coastlines, they pose risks to wildlife and may eventually enter the broader ecosystem and potentially the human food chain.

The authors of the Environmental Pollution study say their findings raise questions about current eco-labeling and biodegradability definitions for wet wipes. They advocate updates to labeling standards, more rigorous real-world testing, and greater scrutiny of products marketed as plastic-free or biodegradable to ensure that advertised claims reflect actual environmental fates. In their conclusion, they call for clearer criteria that consider freshwater conditions and the various factors that influence persistence in rivers and streams.

Fatbergs, the conglomerations of congealed fats, wipes and other waste that can form in sewer networks, illustrate the downstream consequences of consumer disposal choices. The largest fatberg discovered in the United Kingdom stretched about 750 meters (2,460 feet) beneath London’s South Bank in 2017, underscoring the scale of the challenge and the cost of removing such blockages. Public stewardship of wastewater systems requires reconsideration of how products are marketed and disposed, particularly those labeled as biodegradable or plastic-free, to prevent misperceptions that justify flushing.

As researchers emphasize, the path from toilet to river is not a linear or risk-free one. During heavy rainfall, storm systems can overwhelm sewers, increasing the likelihood that wipes and other non-dissolving materials are discharged into waterways and coastal environments. This study adds to a growing body of evidence that real-world biodegradability can differ markedly from laboratory results, reinforcing the need for robust regulations, transparent labeling, and consumer awareness about responsible disposal of wet wipes.