Carspreading fuels policy tug-of-war as Europe leans toward bigger cars

From Paris’ heavy-vehicle parking tax to UK council plans, governments weigh environmental goals against utility, safety, and consumer demand for sport-utility vehicles.

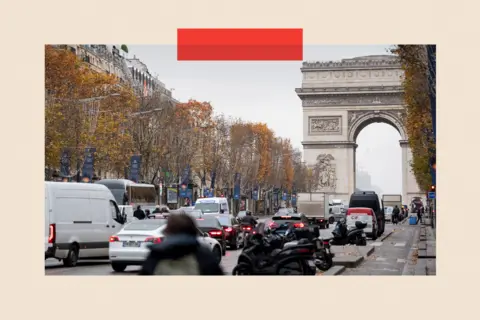

Car sizes are growing across the United Kingdom and Europe, and that trend is prompting cities to rethink mobility, safety, and climate policy. In Paris, city authorities have begun to target heavier vehicles with tougher on-street parking charges as part of a broader push to curb air pollution and congestion. In the United Kingdom, several councils are weighing similar steps, arguing that heavier cars produce more emissions, wear roads more, and pose higher collision risks in urban areas.

In October 2024, Paris tripled the on-street parking charges for visiting “heavy” vehicles, lifting them from €6 to €18 for a one-hour stay in the city center and from €75 to €225 for a six-hour slot. Mayor Anne Hidalgo said the larger the vehicle, the greater the pollution, and that the move would accelerate the environmental transition by tackling air quality. A few months later, city officials said the number of very heavy cars parking on city streets had fallen by about two-thirds. The policy reflects a broader strategy to nudge residents and visitors toward smaller, less polluting transport modes and to direct space to public transit, cycling, and pedestrians.

The policy approach in Paris has begun to influence neighboring cities. In Cardiff, for instance, the council has announced higher parking-permit costs for cars weighing more than 2,400 kilograms (about 5,290 pounds), arguing that heavier vehicles typically produce more emissions, cause greater wear and tear on roads, and pose higher risks in crashes. The plan starts with a narrow slice of models but is designed to tighten the threshold over time. Other local authorities across the UK are weighing similar steps as cities contend with crowded streets and aging infrastructure in the face of rising SUV popularity.

The car market has moved decisively toward larger models. Between 2018 and now, the average width of new cars sold in the UK rose from about 182 cm (5.97 ft) to roughly 187.5 cm (6.15 ft), according to Thatcham Research, which evaluates new vehicles for insurance purposes. The average weight also climbed, from about 1,365 kg (3,000 lb) to around 1,592 kg (3,500 lb). Data compiled by the International Council for Clean Transportation show that the European fleet widened by nearly 10 cm (3.9 inches) between 2001 and 2020, while length grew by more than 19 cm (7.4 inches). Critics argue that there is little space left on Britain’s narrow roads and in town centers for bigger vehicles.

The rise of the sport-utility vehicle, or SUV, has been central to this trend. SUVs now account for a dominant share of many European markets. In 2011, SUVs represented 13.2% of the market across 27 European countries; by 2025, their market share had surged to about 59%. Industry observers say the appeal is practical: buyers like the higher seating position, better visibility, and perceived safety on motorways. For families, the higher seating height and more interior room are attractive, even if that space comes at a cost to urban maneuverability.

For some households, larger vehicles are a practical necessity. Lucia Barbato, a parent in West Sussex who drives a Lexus RX450 hybrid for family duties, says space is essential when juggling kids, bags, sports gear, and even a trumpet in the boot. “On a Monday morning with three boys, three school bags, three sports kits, and a trumpet thrown in the boot there isn’t even room in the car for the dog,” she says. The broader point is that urban residents frequently weigh trade-offs between convenience and the environmental or safety implications of larger cars.

Industry analysts point to profitability as a factor behind the continued growth in SUV sizes. Larger cars often carry higher price points and, in many cases, higher margins. However, manufacturers also emphasize that the cost of building any vehicle—a fixed overhead for design, tooling, and components—favors scale. Some models are closely related to conventional cars; the main differences can be limited to body style, suspension, and seating position, enabling SUVs to command a premium without dramatically higher production costs. Still, the net result is a trend toward bigger, heavier vehicles across the portfolio.

Safety debates around bigger cars are nuanced. Proponents argue that higher structures and more robust crash protection improve occupant safety. Critics warn that taller, heavier vehicles can be more dangerous to pedestrians and cyclists in collisions, and may create blind spots for drivers. Belgium’s Vias Institute warned that a 10-centimeter increase in bonnet height could raise the risk of serious injuries to vulnerable road users by about 27%. Thatcham Research notes that safety programs and stronger occupant protection have indeed required more robust vehicle architectures, contributing to weight growth as manufacturers seek to balance safety with interior comfort and features.

From an environmental perspective, the International Energy Agency has said that, despite efficiency gains and electrification, the shift toward heavier, less efficient vehicles such as many SUVs has largely offset improvements in energy use achieved elsewhere in the global passenger-car fleet. Electric vehicles (EVs) are expected to reduce emissions over time, but the overall benefit depends on how the electricity used to charge them is generated. Because many EVs weigh more than their internal-combustion counterparts, some of the environmental gains could be offset if the electricity mix remains heavily fossil-fueled.

Policy responses vary. In France, penalties are already in place for cars above a baseline weight of 1,600 kg, with an extra €10 per kilogram and a higher rate above 2,100 kg. The scheme, which excludes fully electric vehicles, can add substantial costs to a new car purchase when combined with other emissions-based penalties. Campaigners for tighter UK measures argue that a similar approach could better align consumer incentives with urban transport goals. Tim Dexter, vehicles policy manager at Transport & Environment, contends that the United Kingdom currently serves as a “tax haven” for large vehicles and that it would be fair to require heavier cars to pay more. David Leggett, editor at Just Auto, suggests that policymakers could nudge buyers toward smaller cars, especially in cities, but cautions that ensuring a robust market for city-focused runabouts would be challenging.

Meanwhile, automakers are expanding offerings of smaller EVs to counter imperfect market signals. New entrants and established brands alike are rolling out compact, affordable electric options, including BYD’s Dolphin Surf, Leapmotor International’s T03, Hyundai’s Inster, and Renault’s new 5, with Kia’s EV2 and Volkswagen’s ID Polo slated to follow. Industry observers note that although these small EVs may help rebalance urban mobility, SUVs currently retain a dominant position in many markets. Autocar’s Rachel Burgess says the industry’s shift toward smaller models in an electric era is still evolving, and that trends in demand and pricing will determine how quickly the market tilts away from large vehicles.

Images embedded here illustrate the topic and provide visual context for urban mobility and car design trends as policymakers weigh environmental and safety considerations against the practical realities faced by families and businesses.

Looking ahead, policymakers face a balancing act. The market shows no immediate sign that SUVs will disappear, particularly in suburban and rural areas where practicality remains a key factor. Yet several cities are signaling that policies rewarding smaller, lower-emission vehicles will intensify as urban planners seek to reclaim space for transit, cyclists, and pedestrians. In that sense, the drive to curb car sprawl is less about banning large cars than about managing space, emissions, and safety in increasingly crowded urban environments. The coming years are likely to reveal whether tax incentives, zoning rules, and targeted charges can shift consumer behavior fast enough to achieve climate and mobility goals without compromising the fundamental utility that many drivers rely on every day.