China pledges 7-10% emissions cut by 2035 in landmark climate pledge

Beijing forges an absolute emissions-reduction target across all greenhouse gases to be achieved by 2035, but critics say the plan falls short of the 1.5C pathway even as renewables expansion accelerates.

China on Monday delivered a landmark climate pledge in a video statement to the United Nations in New York, saying it would cut its greenhouse gas emissions across the economy by 7-10% by 2035, while striving to do better. The plan marks the first time Beijing has set an absolute emissions-reduction target on the path toward peak emissions and carbon neutrality by 2060, and it covers all greenhouse gases, not just carbon dioxide. The reductions would be measured from the peak of emissions, though the timing of that peak was not specified by President Xi Jinping.

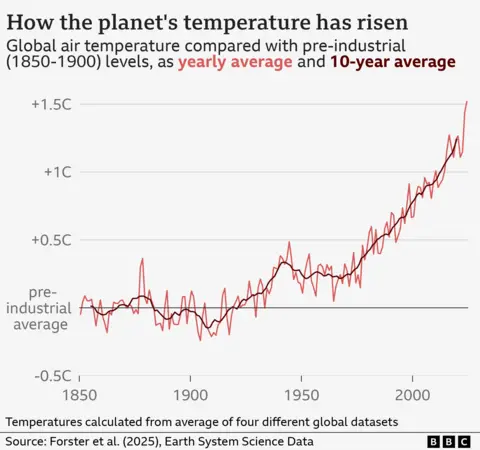

The announcement comes as the United States moves on climate policy with less emphasis on new commitments, and as global leaders prepare for COP30 in Belém, Brazil, in November. It also comes amid a UN-led push to tighten plans under the Paris climate agreement, with countries racing to submit updated nationally determined contributions by the end of September. UN Secretary-General António Guterres said the new plans must be aligned with limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, covering the whole economy and the full suite of greenhouse gases, and that drastic emissions reductions were needed in the coming years to keep 1.5C within reach.

Back in 2021, Xi said China aimed to peak its emissions this decade and reach carbon neutrality by 2060. Today’s pledge, however, is the first occasion on which China set a numeric emissions-reduction target along that trajectory. Xi said the targets represent China’s best efforts under the Paris agreement and would apply to all greenhouse gases, with progress measured from the peak—timing for which he did not provide a date.

Taken in scale, the pledge would be consequential. In 2023, China accounted for more than a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions, at about 14 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent. A 10% cut from China by 2035 would amount to roughly 1.4 billion tonnes of CO2e a year. That is a sizable reduction by any standard and would exceed the total annual emissions of some large economies. Yet observers note that the target falls short of what would be needed to keep warming within 1.5C or even well below 2C, according to most climate-model analyses.

"Anything less than 30% is definitely not aligned with 1.5 degrees," said Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. He noted that many credible scenarios for limiting warming to 1.5C require more drastic cuts from China by 2035, often exceeding a 50% reduction relative to a recent baseline.

China has, in recent years, pursued a rapid expansion of wind and solar power. Earlier targets called for 1,200 gigawatts of installed renewables by 2030, a goal Beijing surpassed in 2024, six years ahead of schedule. Some analysts characterized the pledge as a floor rather than a ceiling, suggesting the energy transition could outpace the stated target as Chinese industry continues to decarbonize and new clean technologies scale up. "China's 2035 target simply isn't representative of the pace of the energy transition in the country," said Bernice Lee, a senior adviser at Chatham House.

But the pledge also underscores ongoing tensions in China’s energy mix. Despite rapid growth in renewables, China remains heavily reliant on coal. Last year, coal-fired power generation reached a record high, though early data for 2025 point to a slight decline as solar output climbs. Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute, called the target a sign of decarbonisation beginning after decades of rapid emissions growth, while noting that the country’s overall emissions trajectory remains closely tied to coal and industrial demand.

Proponents of the pledge also pointed to China’s weather-related climate impacts as a reminder of the stakes. The Stockholm Environment Institute recently warned that governments worldwide are planning to produce more fossil fuels in 2030 than would be compatible with keeping warming to 1.5C, illustrating the gap between stated ambitions and policy outcomes.

IMAGE

Supporters also highlighted China’s track record of exceeding international commitments. Li Shuo noted that China has repeatedly surpassed self-imposed targets for clean energy deployment and argued that the 2035 pledge should be read as a floor, acknowledging the potential for stronger action as technologies mature and policy incentives evolve. Li said the pace of deployment could propel the country much further than the stated target over the coming decade, a view echoed by other global climate thinkers who cautioned against judging Beijing by a single number.

Still, the pledge drew skepticism from environmental groups. Greenpeace East Asia’s Yao Zhe said the plan falls short even for those with tempered expectations, while others argued that the 2035 window is already insufficient to keep 1.5C within reach given emissions in 2023 and the scale of growth in energy demand and industry.

As the UN meeting advances and COP30 approaches, analysts say the real test will be how China translates the pledge into policy measures—coupled with clear milestones and transparent reporting—so that the 2035 goal becomes a meaningful step toward deeper cuts in the 2040s and beyond. The coming months are likely to shape how foreign governments, financial markets, and climate activists assess Beijing’s commitment within the broader global effort to limit warming to 1.5C.