Decoupling Growth From Emissions: How Diet, Cars, and Land Use Could Engineer a Climate-Friendly Economy

A policy argument urges growth without environmental wreckage by rethinking meat, transport and land use, paired with rapid clean-energy deployment.

A new policy discussion argues that the United States can grow the economy while dramatically reducing its environmental footprint. Advocates say the route forward is not to shrink national income but to target the biggest inefficiencies driving emissions: meat and dairy production and a transportation system dominated by cars. The analysis builds on a widely discussed policy book that imagines a future where half the planet is densely built for human needs while the other half remains a vast wilderness, suggesting prosperity and nature can coexist rather than compete.

The core idea is to decouple growth from emissions by extracting more economic value from fewer environmental harms. Proponents say the path forward requires rethinking two entrenched habits that rip through land and energy: meat- and dairy-heavy diets and a car-dependent way of moving around. The arguments call for a shift that preserves living standards while freeing up land for nature and climate-friendly use. They acknowledge the political and cultural barriers in the United States but contend that the necessary trade-offs are both feasible and essential for liberal democracies that want to maintain prosperity while stabilizing the climate.

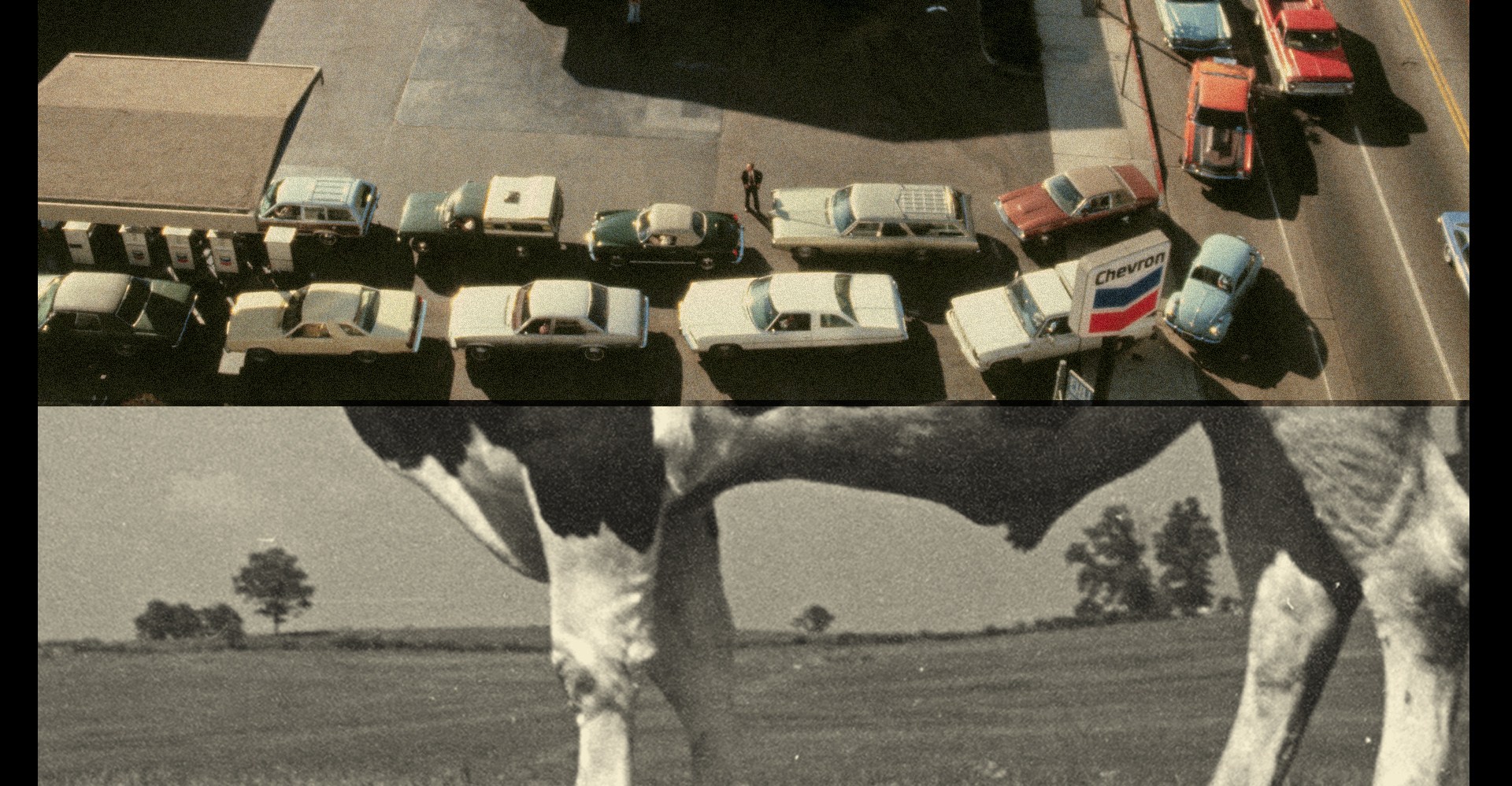

Two great efficiency sinks It’s well known that meat and dairy and cars are major sources of emissions and land use. Together they account for around a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions globally and within the United States. Animal agriculture consumes more than a third of habitable land globally and about 40 percent of land in the lower 48 states, underscoring how farming choices and food systems shape the climate twice as much as most people appreciate. The energy intensity of these choices matters as much as the energy itself: beef emits roughly 70 times more greenhouse gases per calorie than beans, and poultry about 10 times more than beans. Per mile travelled, rail transit emits roughly a third of what driving does, while walking emits essentially nothing. And yet, neither meat nor cars is inherently indispensable to an advanced economy; in the United States, agriculture and the auto sector together employ far fewer people than the service economy, which spans health care, education, finance, and retail.

The structure of the economy matters here. Agriculture and vehicle manufacturing form a relatively small slice of GDP in advanced economies, and the broader service sector dominates. That means a shift away from meat and cars could, in principle, be managed without shrinking overall GDP, by reorienting production toward less land-intensive foods and more efficient, lower-emission transportation. Even so, the transition would entail business restructuring and workforce adjustments in communities tied to meatpacking, feed crops, and automotive manufacturing. Policy design would need to help workers through retraining and regional adaptation as demand patterns shift.

Despite decoupling progress in energy—where emissions have fallen about 20 percent since 2005 while real GDP rose roughly 50 percent—food and mobility remain stubborn frontiers. A megawatt is a megawatt, whether from coal or solar, but shifting diets from meat to plant-based foods represents a much less straightforward transformation of daily life than swapping gas-powered cars for electric ones. The case for changing eating habits rests not only on emissions data but on land use, biodiversity, and public health, all of which could improve as meat and dairy demand declines.

The car question is equally thorny. Electrification helps, but EVs are not a panacea. They require large amounts of energy to produce batteries, and their deployment is constrained by mineral supplies and electric-grid needs. Some researchers have suggested that the real question isn’t simply whether to replace gas cars with EVs, but whether society should still rely on cars to the same extent. A widely cited study argues that even with aggressive electrification, transportation systems would not meet climate targets if car dependence remains the baseline for daily life. The better path may be to reduce the number of miles traveled and to reimagine urban form so that people can live closer to work, services, and transit.

The land question follows from this logic. Car-oriented sprawl fragments wildlife habitat and demands more land for parking, roads, and low-density housing. Estimates suggest the United States spent an area roughly the size of New Jersey on parking alone as of the early 2010s, while housing occupies far less land than farming but still drives a misallocation of land resources. The implication is clear: reorganizing where and how people live—densifying in walkable, transit-accessible areas—could dramatically reduce land use and commuting emissions without eroding living standards.

Policy paths and practical challenges Analysts propose a menu of practical policies. One priority is to shift consumer demand toward plant-based foods, supported by public investment in plant-based meat alternatives research and targeted nudges to steer consumer choices—policies that could be paired with stronger rural and urban land-use planning to support a denser, more transit-friendly housing stock. In parallel, reforming zoning and permitting to enable greater housing density near city centers could sharply cut the miles Americans drive, reduce vehicle infrastructure costs, and ease housing shortages that constrain economic growth.

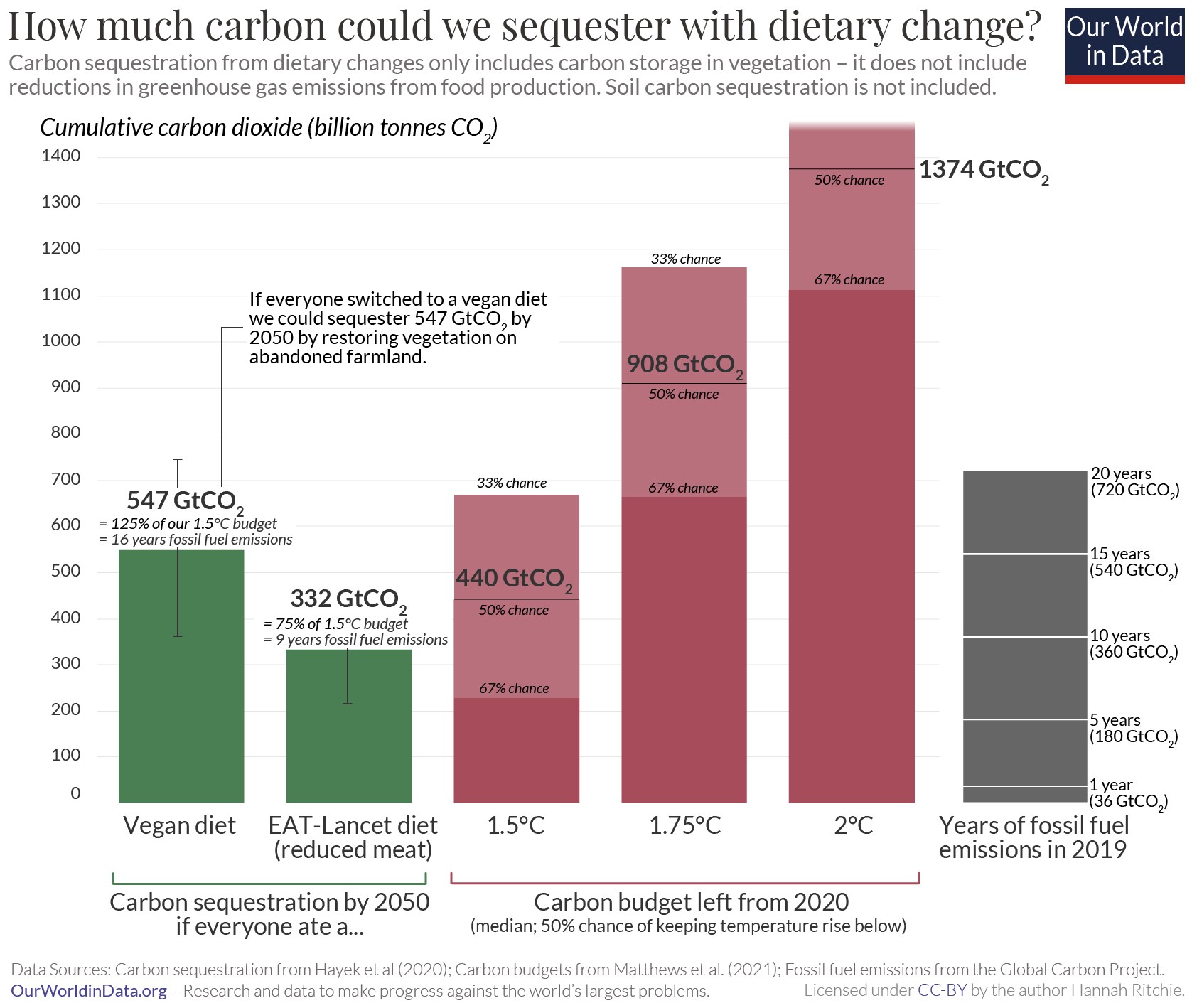

In parallel with diet and mobility reforms, the analysis emphasizes the carbon opportunity cost of land use. Reducing meat consumption could dramatically free up land for rewilding, offering carbon sequestration benefits that some studies quantify as double-digit years’ worth of current emissions avoided. A canonical assessment estimates that a 70 percent reduction in global meat consumption could eliminate roughly nine years of projected carbon emissions, while a global shift to plant-based diets might cut emissions by a broader margin. Other research suggests that a rapid phaseout of animal agriculture could effectively freeze the growth of all greenhouse gases over the next several decades, buying time for the broader decarbonization of energy, industry, and transport.

The argument also highlights the opportunity to reallocate resources toward a low- or no-meat diet and a transportation system less centered on single-occupancy cars. Reducing the “meat and cars” burden could free up capital, labor, and land that could be redirected to higher-value services and more sustainable energy infrastructure. Yet the authors acknowledge the political economy of such a transition: workers in regionally concentrated meat-processing hubs and auto plants could face job losses, and public acceptance is not guaranteed. The path forward, they argue, is not to shrink the economy but to evolve it—toward higher efficiency, less waste, and a more resilient, climate-smart form of growth.

Challenges and the broader context The climate and environment debate has long wrestled with the tension between economic growth and ecological limits. The vision advanced here—an economy that grows while reducing its environmental footprint—fits within a broader liberal-democratic framework that seeks to maximize freedom and opportunity while protecting common resources. The policy package requires close alignment of agricultural policy, urban planning, energy, and transportation reform. It also demands a rethinking of consumer culture around meat and mobility and a willingness to experiment with public incentives and regulations that may be politically controversial.

A broader takeaway is that the path to sustainable growth may rely less on any single technology and more on reimagining everyday life. The authors argue that the two biggest efficiency sinks in modern life—meat-and-dairy production and car-dependent transport—are not fixed destinies. With policy that channels investment toward land-efficient farming, plant-based options, denser urban development, and rapid renewable deployment, the economy could continue to grow without sacrificing the planet.

The argument remains theoretical in the sense that it depends on political will and public buy-in, but it frames a practical question for climate politics: can a high-income society reorganize around fewer, smarter, and more sustainable choices without tipping into lower living standards? The evidence cited suggests that it can, and that doing so may also yield ancillary benefits for health, biodiversity, and resilience in the face of climate shocks.

As policymakers weigh the potential gains against the political costs, the overarching message is clear: if growth is to endure in a warming world, it must be steered toward efficiency, not merely magnitude. The debate, informed by data on emissions, land use, and the social dimensions of diet and mobility, invites a rethinking of what prosperity looks like in the 21st century and how best to protect both human flourishing and the ecosystems that sustain it.

The broader agenda includes accelerating clean-energy deployment, expanding electrification where it makes sense, and designing cities and neighborhoods that reduce the need for long car trips. The question now is whether policymakers can translate these ideas into concrete reforms that align economic incentives with environmental imperatives, while keeping a robust standard of living for a growing population.