Green steel startups seek to revive US production with electric smelting

Boston Metal and peers are developing high‑temperature electrochemical methods to extract iron with electricity, aiming to cut carbon and enable smaller, local mills

Startups pursuing so‑called green steel technologies are attempting to revive parts of US steelmaking by replacing fossil‑fuel‑driven blast furnaces with electric processes that remove oxygen and impurities from iron ore.

At a small industrial and retail estate in Woburn, Massachusetts, Boston Metal operates a compact experimental plant alongside businesses such as a daycare centre and a gym — an arrangement the company cites as an example of how future steel production could be sited much closer to communities than traditional integrated mills. "People are dropping off their kids. That kind of shows you an extreme example of what the future of steel looks like," said Adam Rauwerdink, vice president of business development at Boston Metal.

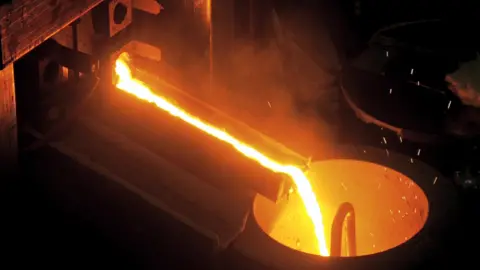

Boston Metal describes its process as an electrochemical route that distributes iron ore particles in an electrolyte and uses electricity to heat the mixture to roughly 1,600 degrees Celsius. At that temperature, molten iron separates from oxides and other contaminants and can be tapped off, leaving waste material behind. The approach aims to perform the ore‑to‑iron step without the coke‑fired blast furnaces that have powered most primary steelmaking for more than a century.

Traditional iron extraction relies on blast furnaces that consume large quantities of coal or other fossil fuels to reduce iron oxides to metallic iron. Steelmaking is a significant source of industrial carbon emissions globally, and companies developing electric smelting methods say their technologies could greatly reduce greenhouse gas output if paired with low‑carbon electricity.

The Boston Metal pilot is one among several ventures in the United States and abroad pursuing electrochemical and other low‑carbon routes to iron and steel. Backers say the technologies could allow smaller, more modular production sites that require less of the heavy infrastructure of traditional integrated mills, potentially reshaping where and how steel is made.

Developers stress that the technologies remain at early commercial stages. Key challenges include scaling processes to the volumes required by the construction and manufacturing sectors, lowering capital and operating costs, securing continuous supplies of low‑carbon electricity, and managing novel waste streams and byproducts in accordance with environmental regulations. Industry observers say resolving those issues will be essential before the new processes can displace conventional blast‑furnace routes at meaningful scale.

Proponents also argue that smaller, electric‑based plants could support regional supply chains and jobs while reducing the need to transport intermediate products long distances. Local siting, however, will hinge on permitting, grid connections and the availability of renewably generated power.

Policy measures and market incentives will influence the pace of adoption. Governments and companies seeking to meet emissions targets have begun to fund pilot projects, set low‑carbon procurement standards and explore carbon pricing mechanisms that could make green steel more competitive. Developers say sustained demand from automakers, builders and other large buyers will be critical to justify investment in scaling new plants.

For now, pilots such as Boston Metal's in Woburn are intended to validate technical performance and demonstrate that electric extraction can produce high‑quality iron suitable for downstream steelmaking. If those demonstrations translate into larger commercial plants, supporters say the technology could play a role in reducing the climate footprint of one of the world's most essential industrial sectors.