How to Know When Outdoor Air Is Safe: Experts on AQI, Monitors and Personal Risk

Amid rising wildfire smoke and conflicting air-quality scores, researchers urge combining official monitors, local sensors and behavior changes to reduce exposure to PM2.5

Outdoor air quality can vary widely over the course of a commute or a day, and several common ways of measuring pollution can give conflicting results, experts say. The divergence matters because fine particulate matter known as PM2.5 is linked to increased risks for heart disease, stroke, dementia and other chronic conditions, and because intensifying wildfires are driving large, regional pollution events.

Researchers and public-health officials say people should use multiple information sources to assess short-term hazards and longer-term exposure. Federal air-monitoring stations run by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency provide the most accurate, regulatory-grade readings and feed the agency’s AirNow site, which also issues regional forecasts and email alerts for broad events such as wildfire smoke. Private networks and weather services draw on other data streams—crowdsourced sensors such as PurpleAir, weather-company forecasts such as AccuWeather’s and personal portable monitors—to fill in local differences that official stations can miss.

PM2.5 refers to airborne particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers, much thinner than a human hair, that can penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream. Studies cited by experts show health effects across a range of exposures: researchers at Cambridge University reported that every 10 micrograms per cubic meter of long-term PM2.5 exposure was associated with a roughly 17 percent higher risk of dementia, and research cited by NYU’s George Thurston found pediatric asthma emergency visits dropped 41 percent in the month after a Pittsburgh plant stopped fossil-fuel emissions.

Those health risks underpin the need for usable and accurate air-quality information, but current tools have limitations. Official EPA stations are high quality but expensive to install and maintain, leaving gaps in coverage, particularly in less populated or rapidly changing areas. Crowdsourced sensor networks fill in local detail—detecting pollution spikes from traffic, nearby burning or industrial releases—but individual sensors are lower cost and lower precision, can degrade with time, and are not uniformly installed or maintained.

Forecasting adds further uncertainty. Weather-driven factors such as sudden wind shifts can transport polluted air into a community within hours or disperse it just as quickly. Strong sunlight can accelerate chemical reactions that raise ozone levels. Researchers note that AQI forecasts are often less reliable than weather forecasts because pollutant concentrations are sensitive to local sources, mixing in the atmosphere and rapid changes in meteorology.

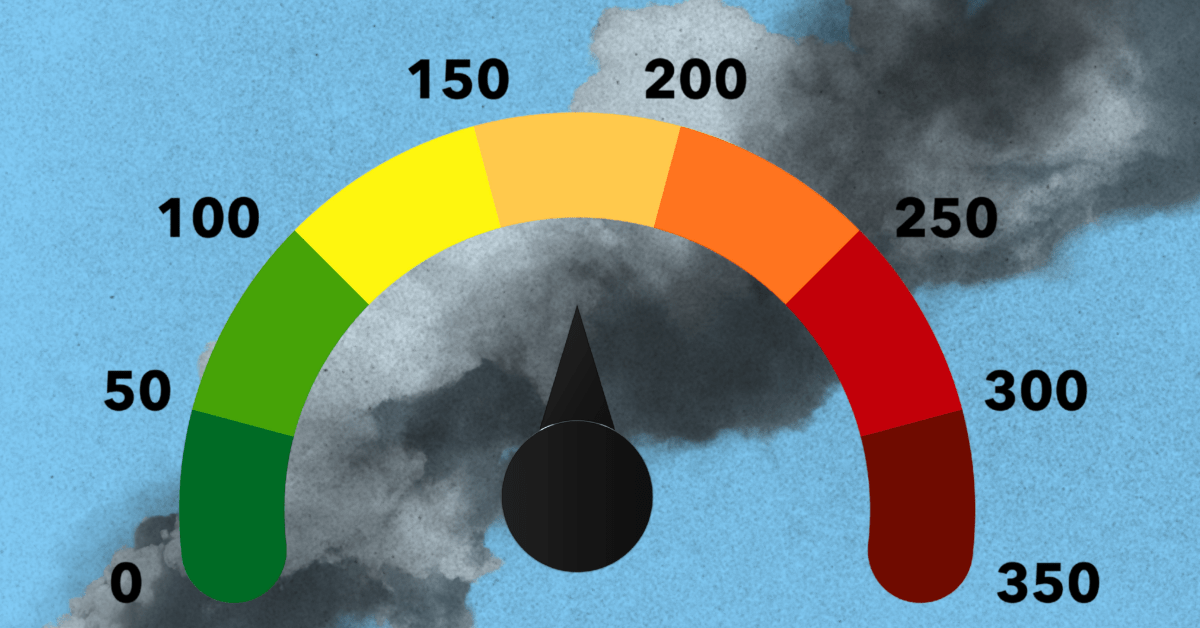

The way organizations translate pollutant readings into an air-quality index also differs. The EPA’s daily AQI flags PM2.5 as "unhealthy" when 24-hour concentrations exceed 35.5 micrograms per cubic meter, while the World Health Organization’s guideline for the same period is 15 micrograms per cubic meter. Some services, including AccuWeather, use the WHO threshold; PurpleAir’s platform allows users to choose which standard to apply. Those different cutoffs mean one app may show "good" air while another shows "moderate" or worse.

Experts recommend a combined approach to understand immediate risk and reduce cumulative exposure. Publicly available regional services such as AirNow can identify broad, multi-county events like wildfire smoke and provide official forecasts and warnings that are useful for planning. Local sensor maps such as PurpleAir’s display near-real-time readings from private and community monitors and can reveal neighborhood-level spikes that regional monitors miss. Weather-company tools that generate hour-by-hour AQI forecasts can help plan outdoor activities, though users should refresh forecasts during fast-changing conditions.

Personal monitors, worn on a belt or held while moving through different environments, can illustrate an individual’s exposure profile and identify high-exposure places such as busy transit routes. These devices are cheaper than regulatory monitors and useful for trends but are less accurate than EPA stations and require appropriate placement and upkeep. Researchers caution that lower-income neighborhoods are underrepresented in many crowdsourced networks, limiting visibility of some communities’ pollution burdens.

Because long-term, cumulative exposure can matter more for chronic disease than isolated peaks, experts emphasize strategies to lower average daily exposure as well as avoiding high-pollution episodes. Practical actions include staying informed through AirNow alerts, checking local sensor maps before extended outdoor activity, limiting outdoor exercise during hotter afternoons when ozone or PM2.5 may peak, and refreshing hourly forecasts during planned outings. For indoor protection, advancing measures such as certified air purifiers for homes and cars and switching from gas to electric stoves can reduce indoor sources of hazardous pollutants.

Scientists also note the limits of color-coded scales and behavioral guidance derived from them. Some researchers urge removing the implication that any level of outdoor air is completely safe, pointing to evidence that even low concentrations contribute to long-term harm. Regulatory and health organizations have established lower cutoff points for annual average exposure—EPA’s and the WHO’s long-term targets differ—reflecting ongoing debate over safe levels.

Policymakers and researchers are pursuing ways to combine multiple data streams to improve coverage and forecasting. The EPA has piloted integrating calibrated crowdsourced data with regulatory monitors to increase local resolution, and weather services are incorporating machine-learning models that process large volumes of observations to refine short-term AQI predictions. Still, scientists caution that no single source currently provides a complete portrait of air quality at all times and places.

For individuals, the consensus among public-health experts is clear: use multiple information sources, learn local patterns that affect air quality, and take concrete steps to reduce both short-term and long-term exposure. While outdoor air is often beyond immediate personal control, people spend most of their time indoors, and improvements to indoor air can substantially lower overall exposure and health risk.