Khan expands ULEZ crackdown as repeat debtors face bankruptcy risk

Transport for London tightens enforcement on long-running ULEZ debts, with bankruptcy proceedings and wage and asset recovery under consideration as pollution rules widen across Greater London.

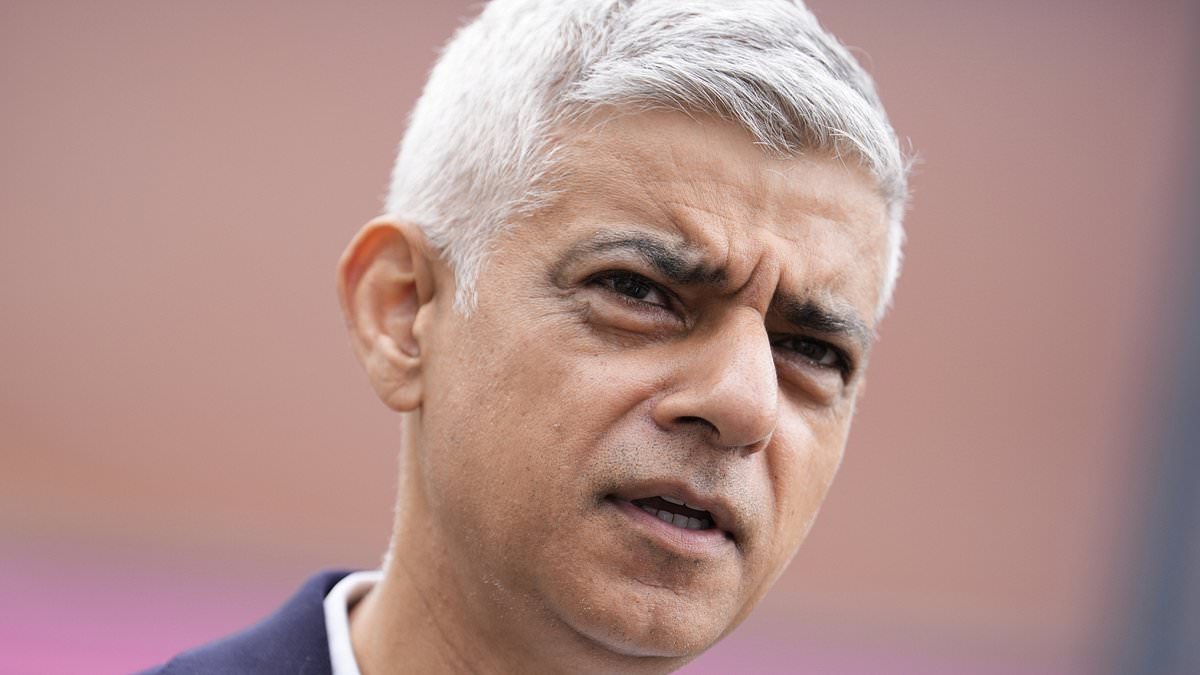

London Mayor Sadiq Khan on Monday announced a renewed crackdown on Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) offenders, saying repeat debtors could face bankruptcy as enforcement expands across the capital. The move comes as TfL, which Khan chairs, intensifies action against a specific group of drivers with long-running ULEZ debts while continuing to defend the scheme as a public health measure.

The ULEZ, implemented in 2019 to curb roadside pollution, charges a daily £12.50 to drivers of non-compliant vehicles travelling through most of Greater London. TfL said it will target a defined cohort with persistent debt, potentially pursuing bankruptcy proceedings, requiring debtors to pay what they owe before selling any property, or enabling direct deductions from wages. Penalties can escalate to £280 if a penalty charge notice (PCN) is ignored and the matter is brought to enforcement.

TfL has said it is also simplifying PCN formats to improve readability and incentivize timely payment, part of a broader effort to recover unpaid charges. Non-payment of the ULEZ charge can lead to a PCN, with enforcement actions possible if the notice is disregarded.

Debt data highlighted the scale of the challenge: about 94% of ULEZ debt is attributed to individuals with four or more outstanding PCNs. The total value of unpaid ULEZ PCNs stood at £789 million at the end of the last financial year, three times the roughly £250 million owed by mid-2023. TfL said the figures underscore the financial strain on some Londoners who face the need to replace older, non-compliant vehicles or absorb recurring fines.

The authority has already begun using an intelligence-led approach to track debtors across different addresses, and has expanded data sharing with national bodies such as the Department for Transport and the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA). In the first half of this year, TfL said it recovered £16.5 million in road user charges and seized more than 530 vehicles through its enforcement program.

Alex Williams, TfL’s chief customer and strategy officer, said the agency recognizes the need for bold solutions to tackle the city’s public health crisis and air-quality concerns, and that ULEZ serves that purpose. He noted that roughly 97% of vehicles driving in London are now compliant, and emphasized that the program targets a small minority of persistent evaders rather than the broad driving public. “If you receive a penalty charge for driving in the zone, you should not ignore it. Your penalty will progress to enforcement agents to recover what you owe, and there is a risk that your vehicle and other items of property will be removed. If you're facing financial difficulties, engage with our staff who can consider your individual circumstances and work with you,” he said.

ULEZ began as a central-London scheme and was extended in 2021 to cover the North Circular and South Circular roads. In 2023, the zone expanded to all of Greater London, spanning more than 580 square miles and encompassing some nine million residents. TfL has argued the expansion was necessary for public health, while critics say it has hit outer London businesses and shoppers, with mixed effects on local economies.

There is evidence of economic impact in outer London, where high-street spending fell in the year after expansion. TfL’s data show Barking and Dagenham experienced the largest decline in high-street spend, down about 13.25%, while other outer boroughs also posted declines or modest shifts. Eight of London’s 33 local authorities saw increases in high-street spending after expansion. Analysts note the data point to a complex relationship between pollution policy and local commerce, with some areas benefiting from cleaner air while others face near-term economic stress.

Khan has defended the policy as a long-term health measure. When the mid-year performance data were released in March, the mayor asserted that earlier projections about the policy’s impact on air quality were conservative. “When I was first elected, evidence suggested it would take 193 years to bring London’s air pollution within legal limits if the current efforts continued. Today, we are closer to achieving that goal this year,” Khan said, arguing that expanding ULEZ was crucial for protecting children’s lung development and reducing the risk of asthma, lung cancer, and other pollution-related illnesses.

A spokesman for Khan reiterated that the mayor remains committed to pro-business policies while pursuing enforcement against non-payers. Critics from the City Hall Conservatives have argued that the data behind ULEZ improvements is imperfect and that the scheme disproportionately burdens outer-London retailers already facing economic pressure. The debate around ULEZ has also touched on security concerns around political leaders; Khan has acknowledged past threats, including a life-threatening Osman warning and a bullet reportedly sent to him, though officials said those incidents are not proof of a direct attack linked to ULEZ policy.

TfL said it would continue expanding its enforcement capabilities in partnership with law enforcement and employ more targeted strategies to recover overdue charges, with an emphasis on protecting London’s air quality and public health while balancing the needs of residents and businesses across the capital.