Large share of U.S. 'farms' are hobby operations or inactive, complicating pollution regulation

USDA counts about 1.9 million farms, but many meet the agency’s low threshold without producing commercially; experts say the figure shields large polluters and skews policy debates

A substantial portion of the properties the U.S. Department of Agriculture counts as “farms” produce little or no commercial output, a reality that researchers say is used by industry and politicians to resist stricter environmental regulation and preserve subsidies.

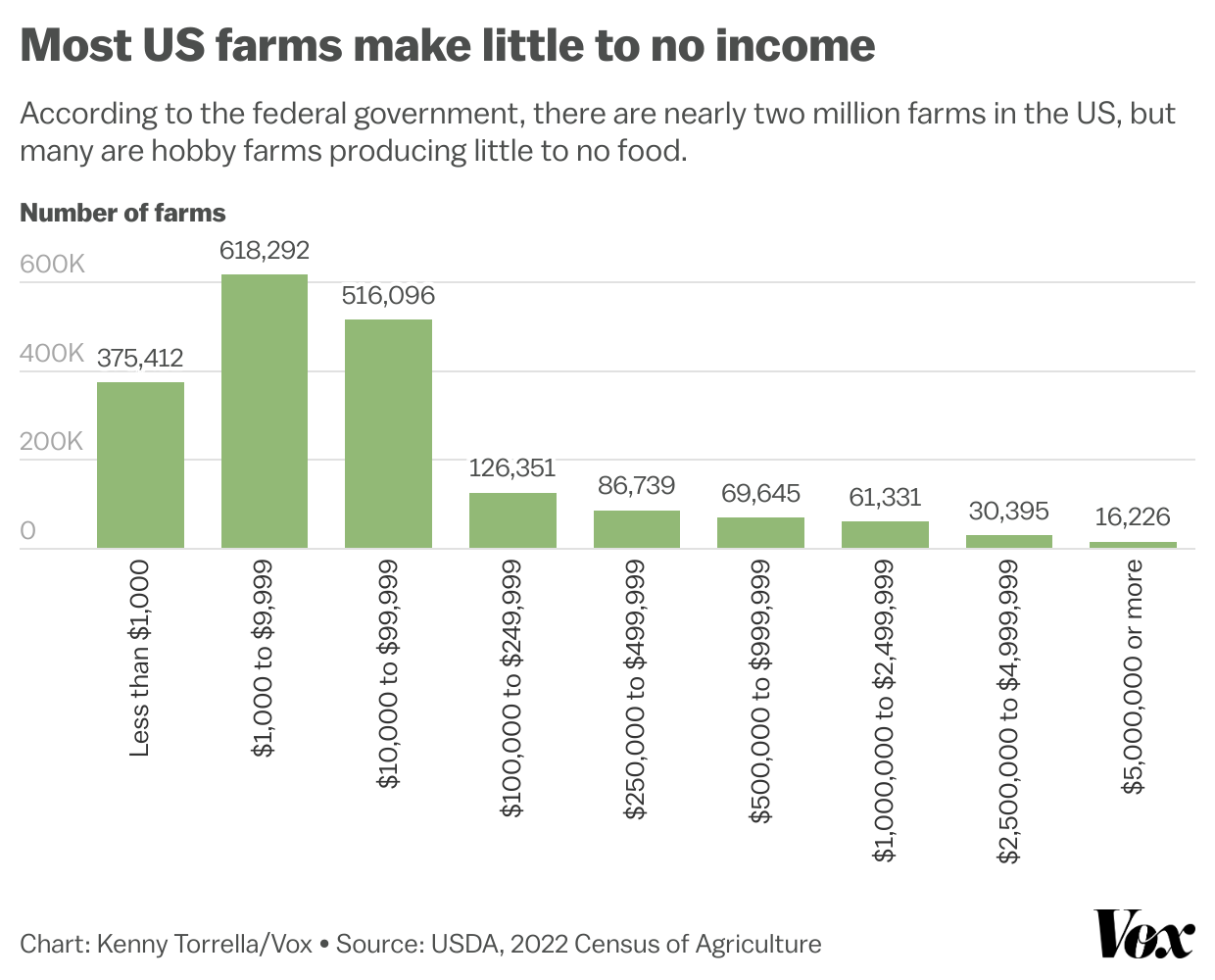

The USDA’s agricultural census reported roughly 1.9 million farms in 2022. But the agency defines a farm as “any place from which $1,000 or more of agricultural products were produced and sold, or normally would have been sold, during the year.” To capture operations that had an unusually bad year, the department uses a points system — based on acreage, number of animals and other factors — to estimate whether a property could have met that $1,000 threshold in a typical year. The rule has broadened over time to include many small acreages and properties that function more like hobby operations than commercial farms.

According to the USDA, more than a quarter of counted farms report zero sales in a typical year. Another roughly 30 percent record between $1,000 and $10,000 in sales, amounts that amount to only a few thousand dollars in potential profit. Excluding those with no sales and those with only nominal receipts reduces the counted universe to about 800,000 operations. Using a higher threshold — for example, treating an operation as a commercial farm only if it sells $100,000 or more in agricultural products — would shrink the count to about 390,000 farms, researchers say.

That difference matters in policy debates. Industry groups, agricultural lobbyists and some politicians routinely cite the larger figure to argue that farms are too numerous and varied to be subject to stricter environmental rules. When the Supreme Court was preparing to hear a consequential Clean Water Act case, an industry brief opened by noting that “there are more than 2 million farms and ranches in the U.S.” In 2022, then-Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack told reporters that farms are not as straightforward to regulate as factories, saying the U.S. has “millions of farms” and suggesting enforcement of broad pollution limits would be difficult.

Researchers and some agricultural economists say the USDA definition and the points system blur important distinctions between commercial agriculture and hobby or conservation properties. Silvia Secchi, a natural resource economist at the University of Iowa, who has written on the topic, said many small operations are counted despite never intending to be commercial enterprises. “More and more of these people are being counted as farmers, even though they never intend to be farmers in terms of being a commercial operation,” Secchi said in published comments. She and others have argued that counting noncommercial operations with midsize and large producers gives political cover to the most intensive, and often most polluting, operations.

The concentration of production in a relatively small number of large operations is stark in several commodities. The USDA census lists 240,530 egg farms, but the vast majority are tiny backyard flocks. Just 347 egg farms — 0.14 percent of the total — raised 100,000 or more birds and accounted for about three-quarters of the nation’s egg production. In hogs, the top 6 percent of pig farms, those with 5,000 or more animals, produce about 75 percent of U.S. pork. Those large facilities are often the primary sources of nutrient runoff, air emissions and other environmental harms linked to intensive animal agriculture.

Industry groups and trade associations typically emphasize the number of farm operators they represent while downplaying the concentration of output. The National Pork Producers Council, for example, has said it represents tens of thousands of pig farms even though a large share of those operations have very small herds. Observers say invoking the image of a broad base of small family farms can be an effective rhetorical shield against regulation and a persuasive argument in lobbying for tax breaks and subsidies.

The USDA’s point system also counts properties enrolled in some conservation programs, in some cases giving “farm” status to land retired from production. Critics note that excluding such retired acres from the farm tally would provide a clearer picture of active commercial agriculture. Others point to the use of farm classification to obtain property tax reductions; some landowners designate parcels as agricultural to qualify for preferential tax treatment despite limited or no commercial agriculture on the land.

Those classification choices have budgetary and policy consequences beyond rhetoric. Some federal funding streams for agricultural research, extension services and other programs are allocated based on the number of farms or the number of people living on farms in a state. Inflated counts that include hobby farms and retired acreage can therefore affect how resources are distributed. They also influence public perceptions about how widespread commercial farming is and who would be affected by regulatory change.

The broader context is a half-century trend toward consolidation in U.S. agriculture, which economists and historians trace to technology, market pressures and federal policies that favored scaling up operations. As midsize and small commercial farms declined in number, larger operations expanded, and the industrial model of confined animal feeding operations became dominant in many commodity sectors. Observers say that history helps explain why both public-facing marketing and political arguments continue to rely on imagery of small farms even as a smaller share of operations account for most production.

Policy analysts and some academics argue that a clearer separation in federal statistics between hobby, conservation and commercial operations would sharpen debate on environmental regulation, subsidies and research priorities. A revised counting method would make it harder for industry groups to rely on a headline number of “2 million farms” in arguments against pollution controls and could guide more targeted regulation of the operations most responsible for environmental impacts.

The USDA census remains the primary federal source for farm counts and characteristics. Any change to its definitions or methods would likely prompt debate among farmers, state taxing authorities, conservation groups and industry representatives. For now, the discrepancy between the headline farm count and the smaller number of commercial producers continues to shape how lawmakers, regulators and the public understand the scale and environmental footprint of U.S. agriculture.