Panama Pacific upwelling fails for first time in decades, scientists warn of severe ecological impacts

A traditionally predictable seasonal rise of cold, nutrient-rich water did not materialize this year, reducing plankton blooms and raising concerns about fisheries and coral reefs

Scientists say a key seasonal ocean upwelling off the Pacific coast of Panama failed to materialize this year for the first time in more than 40 years of records, a disruption that researchers warn could have far-reaching consequences for marine ecosystems and the human communities that depend on them.

The Panama Pacific upwelling normally begins between December and April, peaking between January and April, when persistent northerly winds drive deep, cold, nutrient-rich water to the surface. That annual surge fuels massive phytoplankton blooms visible from space, supports roughly 95 percent of Panama's marine biomass on the Pacific side and underpins fisheries and related industries valued at nearly $200 million a year, researchers said. This year the cool-water surge was delayed and compressed: sea surface temperatures did not fall below 25°C (77°F) until March 4 — some 42 days later than typical starts — and the cool period lasted only 12 days, about 82 percent shorter than normal. The lowest recorded surface temperature this season was 23.3°C (73.9°F), far warmer than historical lows that have approached 14.9°C (58.8°F).

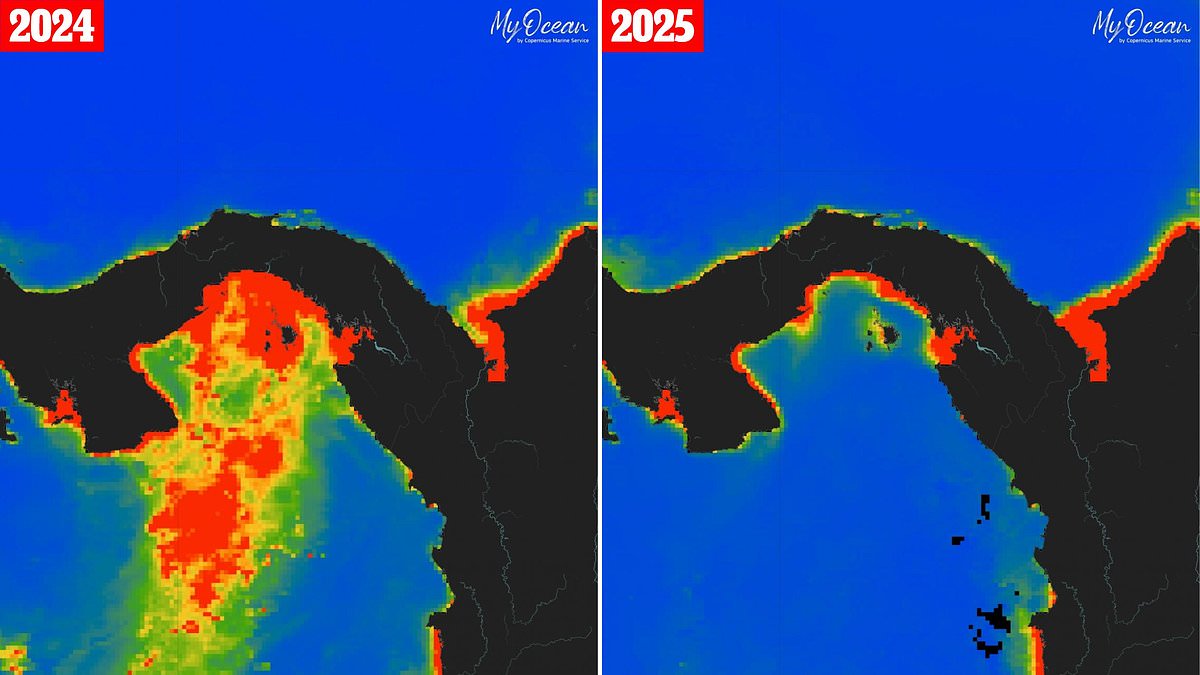

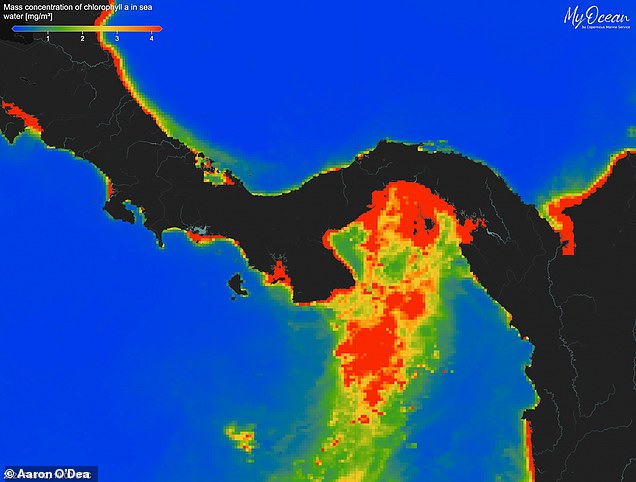

Researchers tracked the failure using satellite measurements of sea surface temperature and chlorophyll concentrations, which serve as indicators of phytoplankton abundance. The expected bloom of microscopic life was largely absent, a change that jeopardizes food sources for small fish and, by extension, larger predators and commercial fisheries. "Over 95 percent of Panama's marine biomass comes from the Pacific side thanks to upwelling," said Aaron O'Dea of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. "Without upwelling, we'll likely see collapsed food webs, fisheries declines, and increased thermal stress on coral reefs that depend on this cooling."

Scientists investigating the event report a "dramatic reduction" in northerly winds, the primary driver of the upwelling. Although when northerly winds did occur they were as strong as in past years, their frequency and duration declined markedly. The team quantified a roughly 74 percent reduction in the number of northerly wind events and a corresponding shortening of wind episodes, which left insufficient force and persistence to generate the typical upward movement of deep water.

The absence of cold, nutrient-rich water has immediate and longer-term implications. Phytoplankton blooms that normally fertilize coastal waters — supporting reef fish, commercially important species and benthic communities — were diminished, according to satellite data. Coral reefs face heightened thermal stress when cooler waters do not arrive to moderate surface temperatures. Prolonged warmth can cause corals to expel their symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae), leading to bleaching and increased mortality.

Researchers cautioned that it is not yet clear whether this year's failure represents a one-off anomaly related to the current state of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) or a longer-term shift in wind and ocean patterns linked to climate change. ENSO cycles include La Niña phases, which alter wind and temperature patterns across the tropical Pacific; investigators noted that this year's conditions included La Niña influences that may have contributed to the reduced northerly winds. At the same time, the team said the possibility of a more permanent change in atmospheric circulation driven by global warming cannot be dismissed.

"This system has been as predictable as clockwork for at least 40 years of records — and likely much longer," O'Dea said. "Climate disruption can upend seemingly predictable processes that coastal communities have relied upon for millennia."

Historical records and paleoecological evidence suggest the upwelling has shaped coastal ecology and human adaptation in the region for thousands of years. The timing and intensity of the upwelling have been tracked in modern records by oceanographic buoys and satellites and inferred in longer-term studies by examining sediment cores and coral growth patterns.

If the Panama Pacific upwelling does not resume in subsequent seasons, scientists say the region could experience cascading ecological effects: reduced recruitment for fish stocks, altered species composition, declines in artisanal and industrial catches, and more frequent or severe coral bleaching events. Those outcomes would carry social and economic costs for coastal communities that rely on fisheries for food security and livelihoods.

Researchers called for expanded monitoring of wind patterns, sea surface temperatures and biological indicators, along with targeted field studies to measure impacts on fisheries, reef health and benthic communities. Better understanding of the interplay between ENSO variability and long-term climate trends will be necessary to determine whether this year's collapse of a previously reliable upwelling marks an extraordinary event or the onset of a new regime in tropical Pacific circulation.

The research team emphasized that restoring climate resilience for marine ecosystems and supporting communities will require integrating scientific monitoring with fisheries management and conservation measures. Scientists intend to publish detailed analyses of this year's observations and to compare them with longer-term records to refine projections of ecological and economic outcomes under varying climate scenarios.