Panama’s Pacific upwelling fails for first time on record, scientists warn of major ecological impacts

Annual cold, nutrient-rich surge that sustains most of Panama’s marine life did not materialize this year; researchers point to weakened northerly winds and possible links to La Niña or longer-term climate change.

For the first time in more than four decades of observations, the Panama Pacific upwelling — a seasonal rise of cold, nutrient-rich deep water that normally occurs between December and April — did not materialize this year, scientists said, raising concerns about widespread impacts on marine ecosystems and coastal economies.

Researchers working on the Gulf of Panama reported that sea surface temperatures this season failed to drop to the normal lows associated with the upwelling. Where surface waters typically cool to as low as 14.9°C (58.8°F) during the event, temperatures this year did not fall below 25°C (77°F) until March 4, a delay of 42 days. The cool period itself lasted just 12 days — about 82 percent shorter than the usual roughly 66-day event — and minimum temperatures reached only 23.3°C (73.9°F), researchers said.

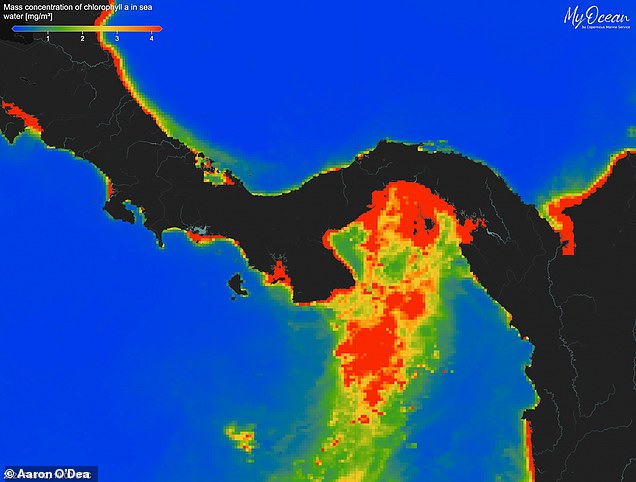

The Panama Pacific upwelling historically supports prodigious biological productivity along the Pacific coast of Panama. Scientists estimate that about 95 percent of the country's marine biomass on the Pacific side is fueled by the annual upwelling, which triggers blooms of algae and plankton visible in satellite chlorophyll measurements. Those blooms are the base of food webs that sustain fisheries and coral ecosystems.

Using satellite data and local observations, researchers said the expected spring bloom was “almost entirely absent” this year. The missing nutrient surge threatens to reduce food availability for fish and other marine organisms and to increase thermal stress on coral reefs that depend on cooler water to avoid bleaching.

"Over 95 percent of Panama's marine biomass comes from the Pacific side thanks to upwelling," Dr. Aaron O'Dea of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute said in comments to media. "It's the foundation of our most valuable marine export industry — nearly $200 million annually. Without upwelling, we'll likely see collapsed food webs, fisheries declines, and increased thermal stress on coral reefs that depend on this cooling."

Scientists investigating the failure identified a dramatic reduction in northerly winds that normally drive Ekman transport and pull deep water to the surface. The number of northerly wind events this season dropped by about 74 percent, and when northerlies did occur they had much shorter durations. Researchers noted that when the winds formed they were as strong as in previous years, but their infrequency prevented the persistent surface forcing required to sustain upwelling.

Upwelling systems occur when persistent winds push surface water away from a coastline, causing deeper, nutrient-rich waters to rise and replace the displaced surface water. In the Gulf of Panama the seasonal upwelling has been a reliable annual feature for at least 40 years of instrumental records and, researchers say, for millennia based on ecological and geologic indicators.

The researchers cautioned that the causes of this year's failure are not yet fully understood. They pointed to concurrent La Niña conditions in the tropical Pacific as a possible factor, noting that La Niña involves changes in ocean surface temperatures and wind patterns across the Pacific. At the same time, the team said longer-term shifts in atmospheric circulation linked to climate change could also be altering the winds that sustain the upwelling.

"The critical unknown is whether this is a one-off event or the beginning of a new normal," Dr. O'Dea said. Researchers said additional studies and longer-term monitoring will be needed to distinguish interannual variability tied to El Niño–Southern Oscillation phases from persistent changes in wind patterns driven by global warming.

Absent upwelling, ecologists warned, the region faces an elevated risk of widespread coral bleaching as warmer surface waters reduce the symbiotic algae that corals rely on. Local fishing communities could experience reduced catches and income if zooplankton and small fish fail to proliferate during the months when the upwelling normally fuels food webs.

Researchers are continuing to analyze satellite records, in situ temperature and wind observations, and ecological measurements to assess the full extent of the event and its impacts. They urged expanded monitoring and rapid assessment of fisheries and reef health to document immediate changes and inform potential management responses.

The Panama Pacific upwelling plays a central role in the coastal oceanography and marine economy of the region. Whether this year's failure proves to be an anomalous interruption or the start of longer-term change will shape scientific and policy discussions about adaptation and conservation of vulnerable marine ecosystems and the communities that depend on them.