Planned Swedish rare‑earth mine could sever Sami reindeer migration and threaten culture

Deposits at Per Geijer, billed as Europe’s largest, would fragment grazing lands already stressed by climate change and the expansion of an iron‑ore mine

KIRUNA, Sweden — Sweden’s plans to develop the Per Geijer rare‑earth deposit in the far north risk severing historic reindeer migration routes used by the Indigenous Sami, herders and experts say, threatening a way of life that has persisted for generations.

The state‑owned mining company LKAB has identified Per Geijer as Europe’s largest rare‑earth deposit and says development could reduce the continent’s reliance on China for critical minerals used in electronics, electric vehicles and renewable technologies. LKAB has signaled hopes to begin extraction in the 2030s, though the company says it is still exploring technical and social solutions.

Sami reindeer herders in the Gabna village, located about 200 kilometers (124 miles) above the Arctic Circle, say a mine at Per Geijer would cut off routes that bring reindeer from summer mountain pastures to winter grazing lands rich in lichen. Lars‑Marcus Kuhmunen, a Gabna herder, said the village would be left with no viable alternative migration corridors if the deposit is opened.

"The reindeer is the fundamental base of the Sami culture in Sweden," Kuhmunen said. "Everything is founded around the reindeers: The food, the language, the knowledge of mountains. Everything is founded around the reindeer herding. If that ceases to exist, the Sami culture will also cease to exist." Kuhmunen oversees about 2,500 to 3,000 reindeer and 15 to 20 herders; roughly 150 people in his community rely on the herd as a business and a cultural foundation.

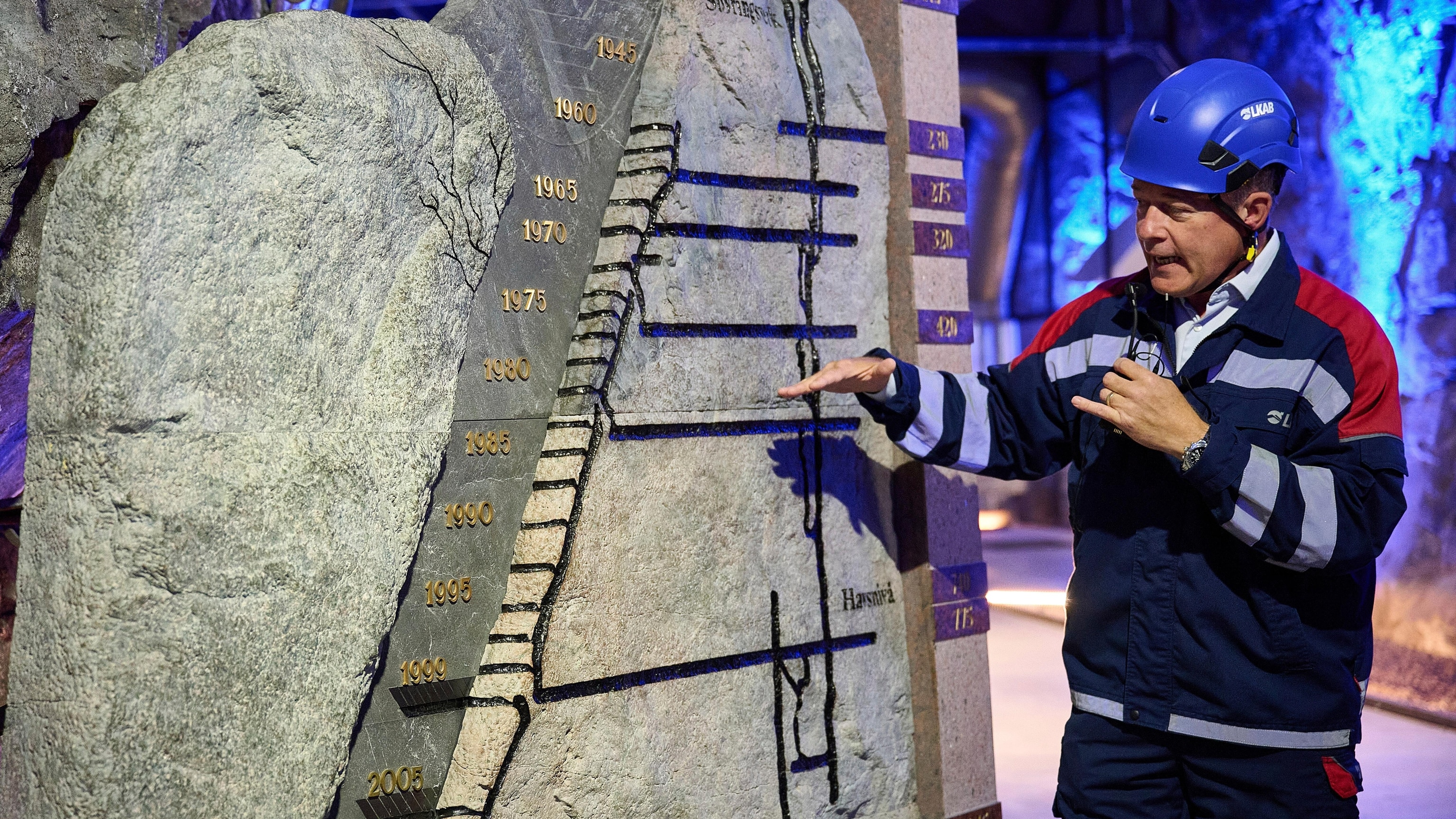

The planned development would add to pressures from the expanding Kiirunavaara iron‑ore mine, the world’s largest underground iron operation, which has already forced longer, more arduous migration routes for Sami herds. Village leaders say they plan to contest any permit in court but acknowledge the legal and financial imbalance between state‑backed mining interests and Sami communities.

"It's really difficult to fight a mine. They have all the resources, they have all the means. They have the money. We don’t have that," Kuhmunen said. "We only have our will to exist. To pass these grazing lands to our children."

Darren Wilson, LKAB’s senior vice president of special products, said the company is seeking ways to assist the herders but declined to specify measures. "There are potential things that we can do and we can explore and we have to keep engaging," he said. "But I’m not underestimating the challenge of doing that."

Climate change compounds the threat to reindeer husbandry in northern Sweden. The Arctic is warming about four times faster than the global average, altering snow and ice conditions that reindeer rely on. Anna Skarin, a reindeer husbandry expert and professor at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, said winter rainfall followed by freezing creates thick ice layers that trap the lichen reindeer feed on, making it inaccessible. Warmer summers have also pushed mountain temperatures as high as 30 degrees Celsius (86 Fahrenheit), stressing animals that are adapted to cold environments.

Those changing weather patterns mean Sami herders need greater geographic flexibility to move herds in response to extreme weather events and uneven forage availability, advocates say. A permanent mine footprint that fragments migration corridors could reduce that flexibility at precisely the moment mobility is most crucial, they warn.

Proposed technical workarounds, such as trucking reindeer between seasonal pastures, have been suggested but experts say they are unrealistic at scale. Skarin noted that reindeer graze while on the move and that forcing continuous transport would deny them access to forage during migration, undermining their ability to build fat reserves for winter.

Sweden recognizes Sami village units, or sameby, as economic entities, and the state sets rules for how many semi‑domesticated reindeer each village may maintain and where they may roam. Sami people number at least 20,000 in Sweden, though an ethnicity‑based census is prohibited by law and exact figures are not available.

Stefan Mikaelsson, a member of the Sami Parliament, described the mounting difficulties of maintaining sustainable reindeer husbandry under combined pressures from climate change and land use. "It’s getting more and more a problem to have a sort of sustainable reindeer husbandry and to be able to have the reindeers to survive the Arctic winter and into the next year," he said.

The Swedish government and LKAB frame Per Geijer as a strategic asset for Europe’s green transition, pointing to the role of rare‑earth elements in batteries, motors and electronics. Mining proponents say domestic deposits could help diversify supply chains. Opponents counter that the social and ecological costs for Indigenous communities and fragile Arctic ecosystems must be weighed alongside strategic benefits.

Gabna villagers and other Sami groups say they will continue legal challenges and public advocacy to try to protect migration routes and grazing lands. The outcome will shape not only local livelihoods but also the resilience of a cultural practice that Sami herders and scholars characterize as intimately tied to the land.

"How can you tell your people that what we’re doing now, it will cease to exist in the near future?" Kuhmunen said, summing up the stakes as mining planners and policymakers weigh economic, environmental and cultural priorities in a rapidly changing Arctic.