Two Pacific Storms Stir Debate Over Rarity of West Coast Hurricanes

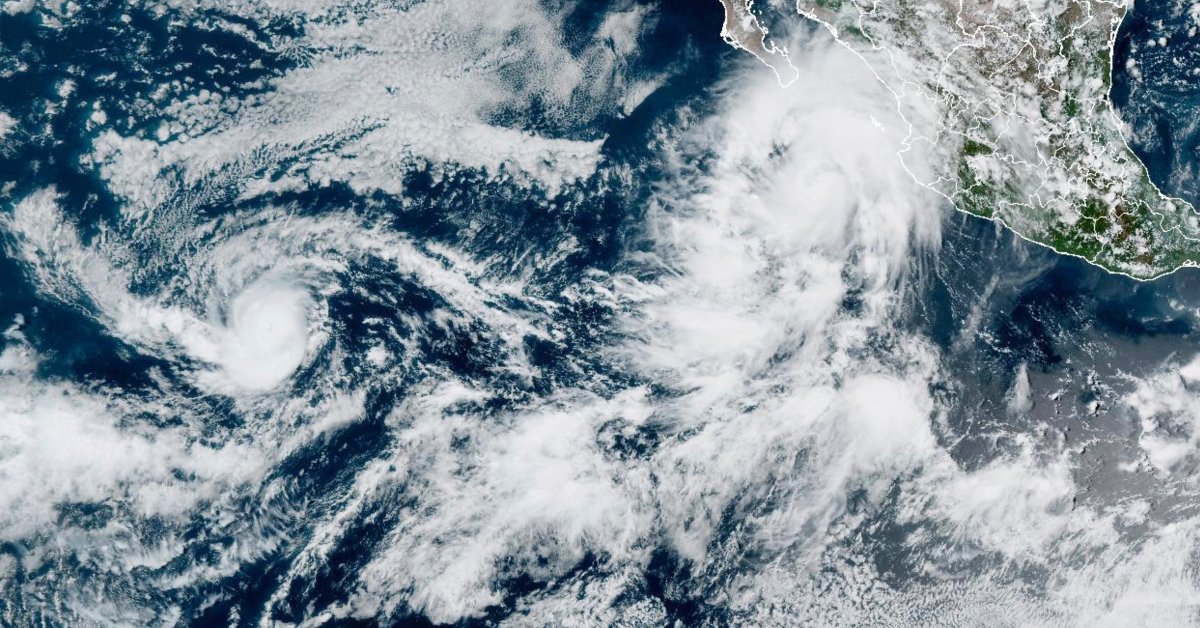

Hurricane Kiko and Tropical Storm Lorena are churning in the eastern Pacific, but forecasters say neither is expected to bring extensive damage to the U.S. West Coast — a region that has only rarely felt hurricane-force winds.

Two named storm systems are active in the Pacific Ocean — Hurricane Kiko and Tropical Storm Lorena — but forecasts indicate neither is likely to produce extensive damage along the U.S. West Coast. Meteorologists say prevailing ocean and atmospheric conditions typically steer eastern Pacific systems westward and weaken them before they approach North American shores.

Kiko strengthened into a hurricane as it moved westward away from the coast, while Lorena remained a tropical storm farther to the south. Current model guidance from U.S. and international weather agencies shows both systems tracking over open water, reducing the chances of major impacts to populated areas on the U.S. mainland or Mexico’s Baja California peninsula.

Historically, hurricanes that reach the U.S. West Coast are rare. Newspapers and weather logs record one of the most notable early events on Oct. 2, 1858, when a storm struck San Diego. Modern analyses of nineteenth-century accounts and surviving weather records classify that system as roughly a Category 1 hurricane, but contemporaneous reports described severe local effects. The Daily Alta California wrote that “a terrific gale sprung up from the S.S.E. … and continued with perfect fury until about 5 p.m.,” and noted that houses were unroofed, trees uprooted and visibility was reduced by clouds of dust.

Even though the 1858 storm was comparatively weak by modern hurricane standards, it stands out because such events are uncommon in the eastern Pacific near the U.S. coast. Scientists point to several factors that typically limit hurricane impacts in the region: cooler coastal sea-surface temperatures, increasing vertical wind shear nearer the coast, and steering currents that more often carry storms westward away from land.

Forecasts for Kiko and Lorena reflect those patterns. Kiko, once organized into a hurricane, has been tracked moving west into the central Pacific, where environmental conditions generally keep systems from intensifying for long periods or turning back toward the North American coast. Lorena, categorized as a tropical storm, has also been forecast to stay over water while gradually losing organization as it encounters less favorable conditions.

Forecasters caution that while major landfalling hurricanes in this part of the Pacific are infrequent, any tropical cyclone can produce hazardous surf, rip currents and localized heavy rain well away from a storm’s center. Coastal communities routinely monitor developments because even distant storms can raise seas and create dangerous surf conditions.

Researchers are continuing to study how long-term climate trends may influence the frequency, intensity and tracks of tropical cyclones in the eastern Pacific. Warmer sea-surface temperatures and changes in atmospheric circulation patterns are among the factors being investigated for their potential to alter storm behavior in decades to come. Scientists emphasize that improving observational networks and forecast models remains essential for timely warnings and preparedness.

For now, authorities and emergency managers along the U.S. West Coast and in Mexico’s Baja California are keeping watch but have not issued widespread alerts tied to Kiko or Lorena. The storms underline both the historical rarity and the continuing need for vigilance: even regions that seldom experience hurricanes keep systems under close observation because of the potential for sudden shifts in strength or track.