UK maps six high-impact climate scenarios, warning of possible extremes by 2100

Researchers outline six plausible, severe risks—from ocean-current shifts to rising seas—that could reshape Britain's climate this century, urging flexible adaptation planning.

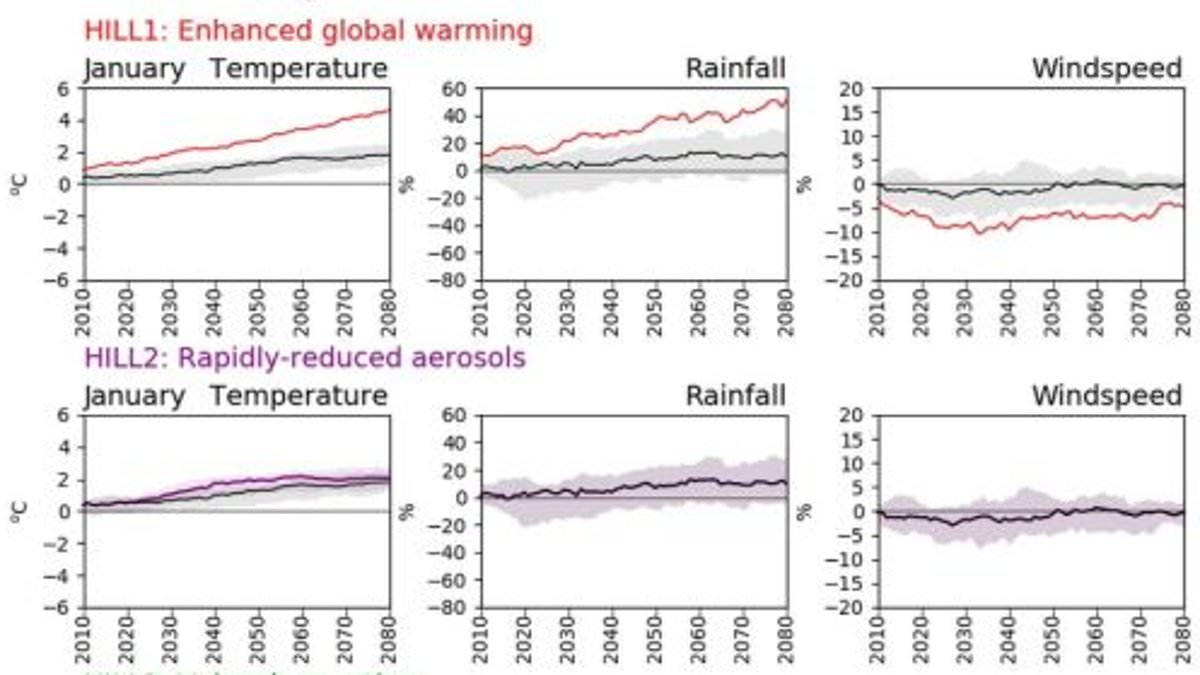

A University of Reading-led study maps six high-impact, low-likelihood climate scenarios that could shape Britain by the end of the century. The researchers describe these as physically plausible risks that policymakers should prepare for, even if they cannot assign precise probabilities. The six scenarios are enhanced global warming, rapidly reduced aerosols, volcanic eruption, stronger Arctic amplification, changes to ocean currents, and rising sea levels. The goal is to understand how climate change could interact with regional systems to produce extreme months and seasons that lie outside current projections.

Under enhanced global warming, temperatures could rise as much as 4°C above pre-industrial levels, yielding hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. In a separate path, rapid reductions in aerosol pollution could remove a cooling effect faster than expected, adding roughly 0.75°C to temperatures by 2040. A volcanic eruption—while not a foregone conclusion—could push temperatures down by about 2.5°C for five years, heightening weather volatility. Stronger Arctic amplification could bring colder winters and heavier rainfall in some regions, while changes to ocean currents—including a potential top-to-bottom shift in the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)—could cause UK temperatures to fall by as much as 6°C by 2050. Finally, rising sea levels could lift Britain's coastline by about 2.2 meters above today’s levels by 2100, threatening low-lying areas.

The study emphasizes that these scenarios are not predictions but high-impact, low-likelihood risks that could interact in unexpected ways. They are described as physically plausible rather than probabilistic forecasts, and the authors say adaptation and resilience planning should be flexible enough to be upgraded if some risks become more likely.

One scenario envisions a slowdown or collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, the global “conveyor belt” that moves warm water northward. If this mechanism weakens or fails, the UK could be about 6°C colder by 2050, with summer rainfall down as much as 35% and winter rainfall rising about 20% across northern areas. Simultaneously, melting ice sheets would push sea levels higher, intensifying coastal flooding risks and reshaping the country’s shoreline.

Beyond 2100, long-range projections show sea levels continuing to rise even if nations meet the Paris climate goals. A separate German-led assessment projected that sea levels could rise by 0.7 to 1.2 meters by 2300, depending on emissions and ice loss from Greenland and Antarctica. The report stressed that every five years of delay in peaking global emissions could translate into roughly 20 centimeters of additional sea-level rise by 2300, underscoring the urgency of rapid mitigation. Lead author Dr. Matthias Mengel of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research noted that current Paris pledges are not on track to meet targets.

On the ground, the study estimates that by 2050 as many as 3.2 million properties could be exposed to coastal and river flooding caused by heavy rainfall, storm surges, and high tides, with 6.1 million properties at risk from more frequent flash floods. The combined effect of higher rainfall in some seasons and rising seas would magnify flood risk across the country, challenging flood management, water supply, and emergency response planning.

Arnell and his colleagues stress that while these scenarios are not certainties, the implications for policy are clear: adaptation and resilience plans must be designed with enough flexibility to upgrade as new information emerges. 'We don't necessarily need to plan or physically build for them, but need to make sure that our adaptation and resilience plans are sufficiently flexible that they can be upgraded if it starts to look as if some of these worst cases look more likely,' Arnell said.