UK waste-bin reform aims to end ‘binsanity’ with standardized four-container system

Government plans would introduce a default four-container scheme for paper, plastics, food waste and residuals, while allowing councils to retain local flexibility and to run longer contracts under existing terms.

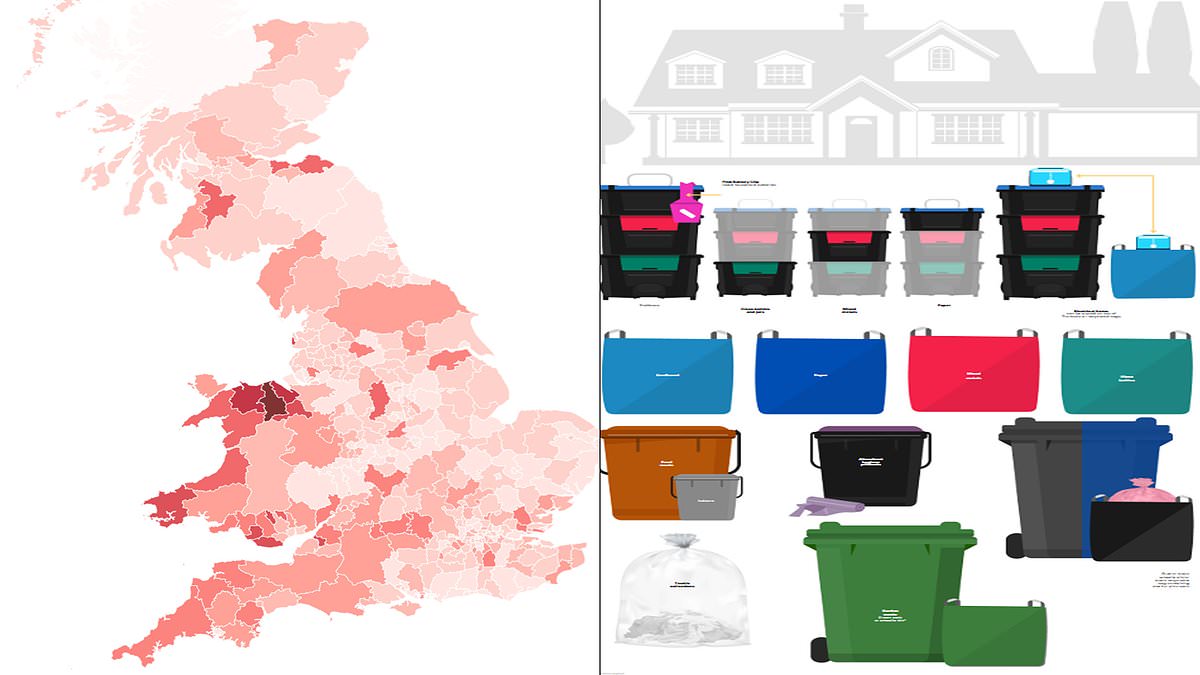

Britain’s fragmented waste-bin system is set for a shake-up as the government moves to end what critics call a postcode lottery of recycling rules. A Daily Mail interactive map shows how councils across the country require households to sort rubbish in as many as a dozen different ways, with bins, bags and specialty containers common in many communities. The map highlights the extent of variation, from multi-bin setups in some Welsh counties to towns that still separate paper and cardboard in addition to other recyclables.

A representative snapshot of the patchwork comes from Denbighshire in Wales, where residents navigate a particularly complex regime. The county operates a 20-page guide online detailing multiple bin types, including a three-bin stacked trolley system and separate containers for items such as batteries and hygiene products, alongside a standard 240-litre bin for non-recyclables and a blue bag for cardboard. Some households also use a smaller indoor container for certain streams and a distinctive orange caddy for outdoor food waste. The Denbighshire example underscores the level of local variation that the reforms aim to simplify.

Under the proposed default rules, households would be given four containers to discard waste: a residual (non-recyclable) waste bin; a food waste container (which can be combined with garden waste where appropriate); a container for paper and card; and a container for all other dry recyclable materials (plastic, metal and glass). The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs says these may take the form of bags, bins or stackable boxes. The intention is to reduce the current confusion and boost recycling rates by providing a consistent, nationwide baseline across councils.

Nevertheless, the reforms would leave substantial power with local authorities, meaning some areas could still operate with more than four containers or different sorting rules. In practice, the extent of change will depend on contract terms and local circumstances. Councils with longer-standing waste-collection agreements may be exempt from the immediate switch, with the new framework phased in as contracts come to an end and new arrangements are put in place.

Denbighshire’s experience illustrates how quickly local innovations can complicate the path to standardisation. In its regime, residents rely on a mix of household bins and specialized containers, including a 240-litre black or blue wheelie bin for non-recyclables, a blue reusable bag for cardboard, an orange caddy for outdoor food waste, and a smaller indoor container for other streams. A series of additional compartments exists for batteries, electronics and hygiene products, while garden waste is kept separate in a green bin. That level of specificity—designed to maximise recovery—highlights why the government wants a simpler, four-container default across the country.

Across England, Scotland and Wales, about 201 councils oversee waste collection using three or four bins and disposal methods, with 114 using four containers. The forthcoming changes are designed to align disparate practices with a more uniform system, while recognising that contract arrangements and local space constraints will require flexibility in how quickly and in what form the standardised approach is adopted. The government says the streamlined approach will help raise recycling rates and reduce waste destined for landfill or incineration.

Even as the policy aims to improve performance, recycling rates in England have hovered around 44% for about a decade. Officials say the streamlined framework could lift that figure to 65% by 2035, but a University of Birmingham study released this week warned that much of the public remains unaware of the looming changes. Researchers highlighted a lack of understanding around terms such as “compostable” and “biodegradable,” and warned that current infrastructure is ill-equipped to handle new waste streams like flexible plastic films and compostables. The report also noted that councils will need extra funding to manage the transition, including capital upgrades to facilities and ongoing operating costs.

Some local leaders already anticipate sizable investments as a prerequisite for readiness. Suffolk County Council, for example, said its recycling facility would require about £12 million in upgrades to cope with the changes. Overall, the government has pledged more than £1 billion to implement the scheme by improving facilities, followed by about £250 million annually to maintain and operate the new system. A Local Government Association spokesperson stressed that public satisfaction with local waste services remains high and cautioned that urban and rural contexts differ; the association also noted that separating paper and card may require additional resources and time, with a staggered rollout from April 2026 to accommodate local needs and existing contracts.

DEFRA says the government will introduce a streamlined approach to recycling to end the postcode lottery, simplify bin collections and clean up streets for good. The department argues that a consistent baseline will enable residents to dispose of waste more predictably and give councils clearer guidelines for investing in processing facilities and collection infrastructure. Critics, however, warn that the pace of change could strain some councils and confuse residents if communications lag behind policy shifts. The government has signaled a balance between national objectives and local flexibility, with exemptions for existing contracts and space-constrained areas.

The broader goal is to curb waste generation and maximize material recovery across the UK, aligning domestic practice with environmental targets and international best practices. As plans move toward implementation, local authorities, waste-management firms and residents will be watching how the new rules balance simpler, more consistent sorting with the practical realities of old contracts, limited space in housing, and the evolving set of recyclable materials.”