Volunteer pilots reflect on one year since Helene devastated western North Carolina

A year after Hurricane Helene pummeled Western North Carolina, volunteer aerial responders recount rescues, donation drops, and the evolving relief effort that followed.

It has been a year since Hurricane Helene devastated parts of Western North Carolina, severing cell service, washing out roads, and leaving communities cut off from help. In the days that followed, small-aircraft pilots and helicopter crews were among the first to reach stranded residents and deliver critical aid, a testament to the ad hoc air-rescue networks that formed in the hours after the storm.

Al Mattress, a helicopter pilot with Total Flight Solutions, recalls an early morning call from a client asking him to check on a family in western North Carolina. He rose quickly, taking to the sky as the storm’s floodwaters were still rising. “Watching it unfold, ya know, this water was still rising,” Mattress told Fox News, adding that he arrived “literally, right after the storm left.” The urgency of those first flights underscored how quickly aerial responders filled a gap left by downed phones and blocked roads.

On the ground, Tim Grant, another Total Flight Solutions pilot, marshaled logistics for dozens of fellow pilots in the ensuing weeks as missions shifted from rescue to donation drops. With support from the United Cajun Navy, Grant said they mobilized nearly every helicopter available. “Everybody donated their time, their effort and their resources to immediately rescue people, or drop off essentials like medicine,” he said. Mattress described the cadence of the operations: once a mission was complete, pilots would climb high enough to locate a cell phone tower outside the debris zone, make a radio call, and report where people had been found and whether they were OK.

The earliest days were marked by frenetic activity. Grant’s team logged 25 rescues on the first day and 30 on the second, then shifted into broader relief work. “We did well over 100 missions, just dropping off food and supplies,” he said. The images coming from Western North Carolina that week—strewn cars in downed streets, mud and debris blanketing mountain slopes—echoed the complexity of the response.

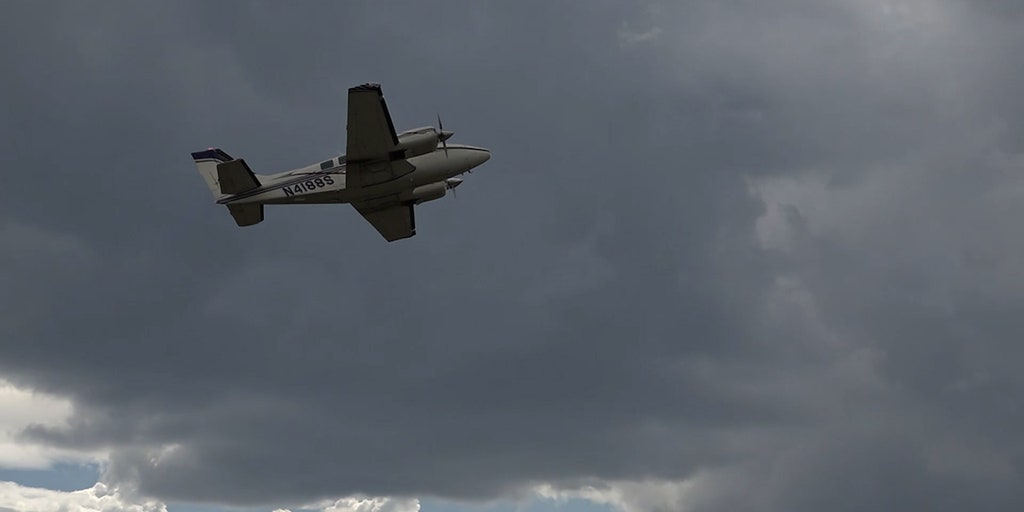

Volunteer pilots in the region were joined by others from across the Southeast and beyond. Austin Lane, a South Carolina pilot who flew a 1960s Baron with a 1,000-pound load capacity, described how donations moved from airport to mountain communities. Lane said his flights carried essentials such as diapers for newborns, canned goods, dietary-restriction items, and insulin. “Delivered diapers for people with newborn babies or delivered canned goods or dietary restrictions and insulin,” Lane recalled. He said volunteers at local airports could load his plane within minutes, enabling six to eight trips a day to reach more distant shelves and drop-off points.

Lane’s involvement came through the Carolina Aviators Network, a group that organized pilots to bring donated goods closer to the mountains. The organization’s rapid coordination reflected a broader volunteer effort that relied on informal networks, local airports, and shared social-media channels to move supplies into hard-hit zones when roads were impassable.

As roads began to clear, state and federal partners joined the effort. The North Carolina National Guard (NCNG) and a coalition of volunteers pushed deeper into the hardest-hit regions, enabling more consistent access for relief organizations. The NCNG provided a count of the airborne relief measures taken in the aftermath: 869 air rescues, including 165 complex hoist rescues—defined as rescues that require a hoist to lift people from dangerous or hard-to-reach locations during a disaster. The Army operated 32 helicopters in support of the mission, including 21 CH-47 Chinooks, 7 UH-60 Black Hawks, and 4 UH-72 Lakotas.

Across the affected area, the scale of the operation extended beyond human rescues. The NCNG reported that 226 pets were rescued by air, 3,638 pallets of food were delivered, and 1,877 tons of cargo were brought in by air. The cooperative effort drew participation from multiple states, including South Carolina, Maryland, Oklahoma, Georgia, Florida, Connecticut, Minnesota, Iowa, New York, and Pennsylvania, as well as local emergency-management teams and nonprofit organizations. The combined airlift and delivery network helped sustain families while roads were being rebuilt and cleanup efforts were organized.

The experience left a lasting impression on those who flew the missions. Grant recalled that the most memorable moment came when a rescue pilot arrived at a rough site and saw arms sticking out from mudslides—an image that underscored the life-or-death stakes of the work, even as the operation broadened to deliver food, medicine, and relief supplies to those in need.

The long arc of the relief effort stretched through the weeks that followed. Grant noted that the organization and allocation of donations—whether aircraft, helicopters, or ground transport—proved essential to extending relief to the mountains. “The people that donated their supplies, their people, their helicopters, whatever it was…that was the best part,” he said. Lane echoed a similar sentiment about the spirit of cooperation that defined the relief effort, noting how quickly local airports were able to assemble and dispatch cargo for deeper inland delivery.

As recovery progressed, the region’s leadership emphasized that the humanitarian response was a collective process. The NCNG and partner agencies used air assets to reach homes that remained cutoff by washed-out roads, fallen trees, and ongoing aftershocks of damage from the storm. The network of volunteer pilots, airport volunteers, and military responders helped stabilize the immediate aftermath and contributed to longer-term recovery by supporting supply chains for essential goods and medications.

Two vantage points crystallize the scale: the near-term necessity of aerial rescues and the longer-term logistics of distributing aid. The aerial missions, which began as urgent life-safety operations, evolved into a broader relief effort that included food, fuel, medicine, and basic supplies. The coordination that emerged among volunteers, local authorities, and military partners demonstrated how communities can mobilize in the absence of standard communication channels and disrupted infrastructure.

Looking back, those who flew the missions describe the relief effort as a turning point for local resilience. The combination of immediate rescue operations and sustained supply drops allowed people to begin rebuilding their lives despite continuing challenges from the storm’s impact. The lessons drawn from Helene emphasize the value of flexible, cross-jurisdictional cooperation and the critical role of aerial support in rural and mountainous regions where roads and cell networks can fail when disasters strike.

As Western North Carolina continues to recover from Helene, organizers say the focus remains on rebuilding and supporting families who lost homes, livelihoods, and routine access to essential services. The experience of the volunteer pilots and the broader aerial-relief network remains a reference point for how communities might respond to future disasters—through rapid, coordinated action, shared resources, and a steadfast commitment to reaching people where they are, even when roads and communications are compromised.

In the year since Helene’s strike, the trajectory of relief in Western North Carolina has underscored the importance of aerial capabilities in disaster response—both for the immediate retrieval of stranded residents and for the efficient distribution of aid to those who remain cut off from road networks and cell-service coverage. The efforts of Mattress, Grant, Lane, and countless others demonstrate how communities can mobilize quickly, coordinate across jurisdictions, and sustain relief operations through the long process of rebuilding after disaster.