After Hours at 40: Was This Secretly Martin Scorsese’s Most Influential Movie of the 1980s?

Forty years on, Scorsese’s SoHo misadventure reshaped late-20th-century city cinema and the way filmmakers blend humor with danger.

New York — As Martin Scorsese’s 1985 dark comedy After Hours marks its 40th anniversary, critics and filmmakers are revisiting the film to ask whether it may be the most influential picture of the decade.

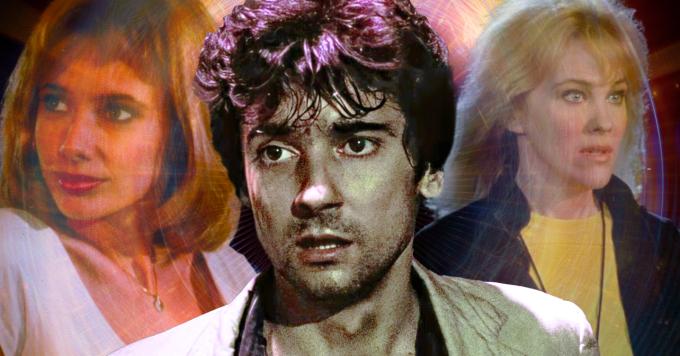

Starring Griffin Dunne as Paul Hackett, a computer-desk worker who ventures into SoHo for a date with Marcy (Rosanna Arquette), the film detours from noir mystery into a Kafkaesque urban fable. The supporting cast includes Linda Fiorentino, Teri Garr, Catherine O’Hara, Bronson Pinchot, and Cheech & Chong, each turning one odd encounter into a rung on Paul’s escalating ordeal.

Rather than a grand conspiracy or conventional pursuit, After Hours relies on cyclical nightmare logic: a single, ordinary night in New York spirals into a series of episodic mishaps in which the city itself seems to conspire to thwart Paul at every turn. It’s a more sly, lighter, but no less menacing mood than Scorsese’s darker crime dramas, a tonal balancing act critics say helped redefine the modern urban comedy. The film’s impulse toward a one-night, anyone-can-get-drawn-in setup has reverberated through decades of late-night dramas and comedies that trade a tight, linear chase for a nocturnal labyrinth of chance encounters.

Critics have pointed to After Hours as a touchstone for later city-at-night stories that mix humor with danger. It sits alongside John Landis’s Into the Night and the year-closer Something Wild as examples of the era’s fascination with ordinary people pulled into a shadowy urban underworld, where the rules of narrative convention bend to a sense of improvisational danger. The influence extends to later, more crowd-focused variants such as Adventures in Babysitting and its loosely related remake The Sitter, which transplant the core idea of a mundane night gone awry into a stakes-laden, family-friendly frame. In other cases, the impulse survives as a tonal mood rather than a plot blueprint: Game Night uses a group dynamic to stage a similar “normies go to the underbelly” energy, while contemporary titles like Under the Silver Lake and Good Time keep the relentless urban drift that After Hours helped crystallize. Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love is cited by some critics as sharing the same blend of genuine tension and offbeat humor, a lineage that traces back to Scorsese’s 1985 misadventure.

The film’s legacy is also read through direct echoes and nods. In Caught Stealing (1998), Griffin Dunne appears in a supporting role as a grungy Lower East Side bar owner named Paul, a playful homage that reframes Paul Hackett’s urban odyssey as a new, lived-in city myth. Spike Lee’s Highest 2 Lowest (in its own way) incorporates a flavor of After Hours, using New York as a restless stage where power, money, and street-level absurdity collide in brisk, unpredictable ways. While After Hours stands apart from Scorsese’s later epics—Gangs of New York and Bringing Out the Dead among them—its DNA can be seen in the way his contemporaries and successors treat the city as an unpredictable, almost co-conspiring character rather than a mere backdrop.

In hindsight, After Hours is often described as a punk-spirited entry in Scorsese’s catalog: appropriate for its downtown setting, it distills a DIY, anti-hero energy that feels at odds with the more polished grand-scale dramas of the era. Yet the film’s influence extends beyond decade-bound nostalgia. It helped establish a template for mixing screwball-era rhythm with a noir-like sense of danger, a template that later filmmakers, including those working decades after its release, have adapted to suit new urban landscapes and contemporary anxieties. While Raging Bull and Goodfellas remain widely celebrated as high-water marks for the director, After Hours is frequently praised for its enduring impact on how cinema portrays the night-laden, imperfect city—and how humor can coexist with peril in the same frame.

Jesse Hassenger, a writer whose work appears in The A.V. Club, Polygon, and The Week, among others, has argued that After Hours may be the closest Scorsese came to punk rock in cinema. His retrospective view situates the film as a turning point that forecasted Scorsese’s ongoing willingness to experiment with tone, genre混, and urban texture, while also shaping a generation of directors who would imitate the film’s nerve in different ways.

In sum, After Hours endures not merely as an early showcase of Scorsese’s range, but as a blueprint for how to map a city’s nocturnal mood onto a feature that looks, feels, and sounds like a dare. Forty years after its premiere, the film remains a touchstone for filmmakers and critics who view the New York night not as a setting to escape, but as a vivid, unruly character that can provoke both laughter and dread in equal measure.