Behind Winnie-the-Pooh: A.A. Milne’s life revealed in new biography

Gyles Brandreth’s Somewhere, a Boy and a Bear reexamines the creator’s complexities, from wartime trauma to a distant fatherhood

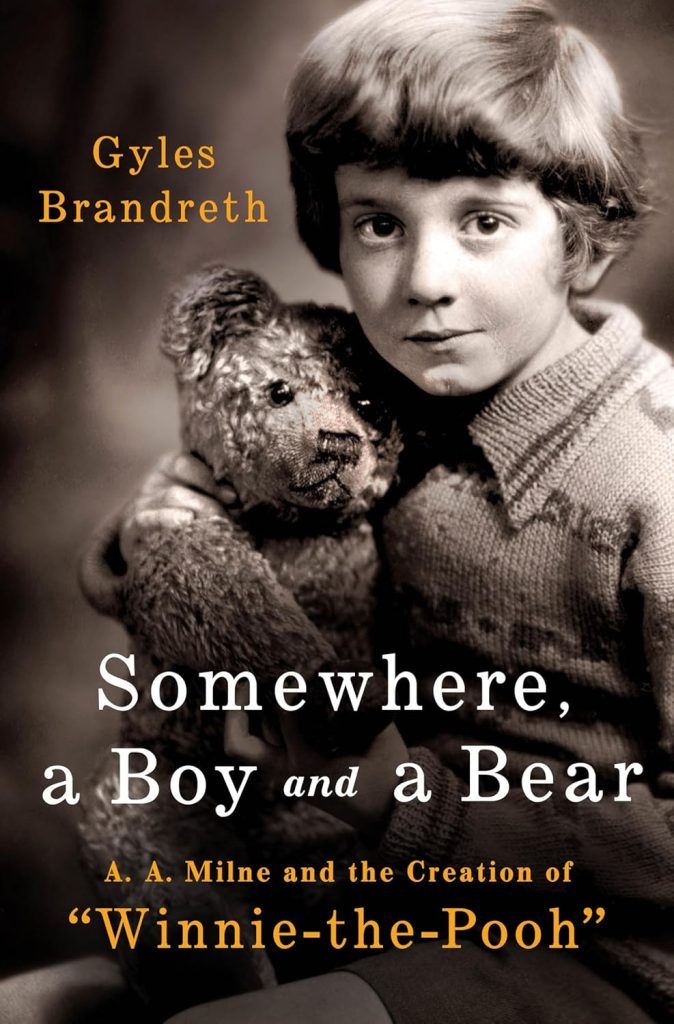

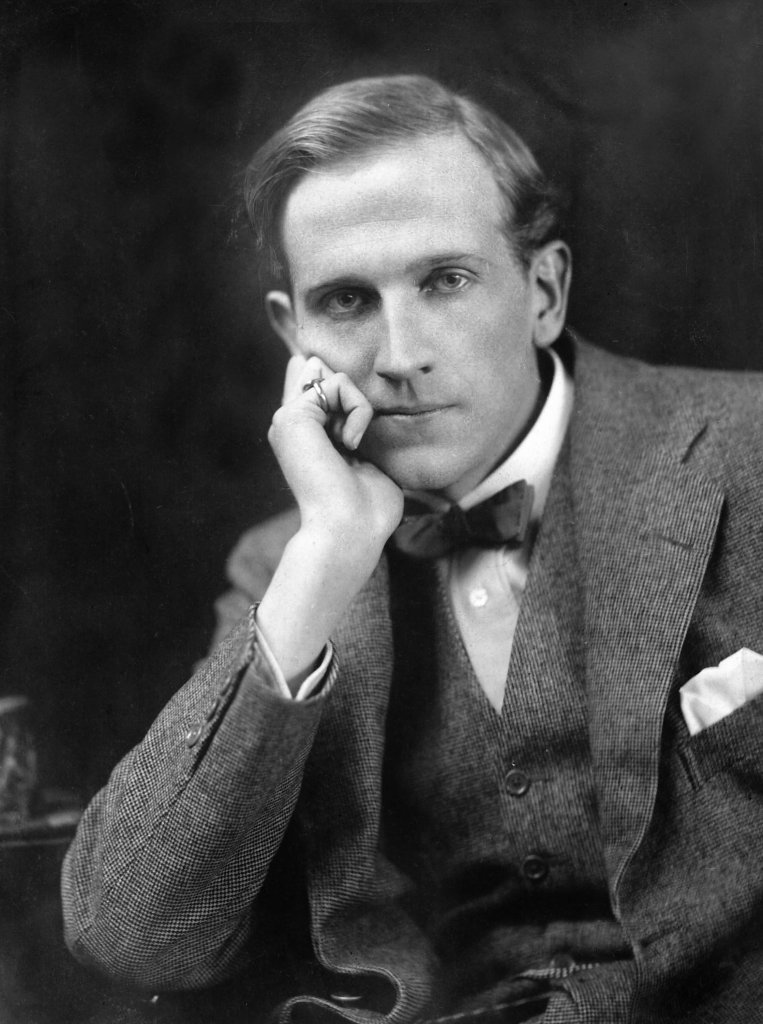

A new biography reexamines A. A. Milne, the man behind Winnie-the-Pooh, and argues that the author’s life was far more conflicted than the honeyed tales suggest. Gyles Brandreth’s Somewhere, a Boy and a Bear: A. A. Milne and the Creation of Winnie-the-Pooh, published by St. Martin’s Press, portrays Milne as a gifted writer whose genius coexisted with disappointment, regret and emotional distance. Since the first Pooh book appeared in 1926, the adventures of a bear who loves honey and his forest friends have sold more than 50 million copies worldwide, a success that would shape the author’s legacy even as it complicated his personal life.

Milne conceived Pooh in part to entertain his young son, Christopher Robin. The stories grew from a boy’s stuffed animals, voices given by his wife, Dorothy Milne, and a family dynamic that blended affection with distance. The boy kept company with the imagined personalities that his mother fashioned for the toys, and Milne began turning those moments into tales. Christopher later recalled that he enjoyed the early attention but also wrestled with the sense that the narratives sometimes framed his life more than they reflected it. “Did I do something and did my father then write a story around it? Or was it the other way about, and did the story come first?,” he told Brandreth. The stories, he said, eventually became a shared life that they “lived… thought… spoke.”

Brandreth’s book underscores a paradox at the heart of Milne’s fame: a writer of sophisticated, adult comedies and psychological portraits who saw Pooh eclipse his wider literary reputation. Milne’s son, Christopher Robin Milne, inspired the character of the same name, yet the father and son grew distant in later years. Christopher later wrote in his 1974 memoir The Enchanted Places that his father’s heart seemed “buttoned-up all through his life,” and he expressed resentment that colonizing fame had come at his infant’s expense. “It seemed to me, almost, that my father had got to where he was by climbing upon my infant shoulders,” he wrote, a line Brandreth highlights to illustrate the emotional toll of the author’s dual achievements.

The biography also canvasses the social circle that surrounded Milne, a cluster of celebrated writers and artists who crossed paths with him. Milne’s friend and contemporary J. M. Barrie, creator of Peter Pan, and others including H. G. Wells, Rudyard Kipling, Arthur Conan Doyle and P. G. Wodehouse, were part of a milieu that could be both encouraging and contentious. Some peers described him as “cagey,” while Wodehouse, noting Milne’s sensitive side, described a “jealous streak” that persisted alongside his charm. The tensions within Milne’s personal life extended to his marriage, as Dorothy Milne herself participated in the comic and dramatic shaping of the Pooh universe, voicing the animals and lending them personalities that delighted readers but sometimes blurred the line between private life and public success.

The shadow side of Milne’s life grew more visible as the author faced the scars of war. A pacifist by conviction, Milne volunteered for the British Army in 1914 and endured the Battle of the Somme, where the sight of a comrade’s death left an enduring imprint. He later described the war as a nightmare, a memory tainted by the physical and moral degradation he witnessed. Those experiences informed his later, more somber works on adulthood, relationships and the aftershocks of conflict, even as Pooh’s cheerful world continued to charm readers.

The family’s personal life carried its own weight. Milne’s older brother, Ken, died of tuberculosis in 1929, a blow that tightened the couple’s emotional reserve. The marriage endured but was punctuated by infidelities on both sides—Dorothy Milne’s relationship with an American playwright and Milne’s with a young stage actress—though the couple remained together for many years. Milne himself grew wary of Pooh’s dominance over his public persona and feared that his literary identity as an “adult” writer—known for manners, detective fiction and portraits of soldiers returning from war—had been eclipsed by the bear’s ubiquity.

Milne’s later years were marked by illness and withdrawal. He suffered a stroke in 1952 and died in 1956 at age 74. Christopher attended the funeral but later ceased speaking to his mother, a rupture that branded their posthumous relationship with complexity. In Brandreth’s account, however, some long-simmering tensions began to ease decades later. When Christopher met Brandreth in the 1980s, he spoke against lingering regrets, offering a tempered reflection on a life shaped by both affection and fault: life is too short for regrets, he said, and childhood memories can be revisited with gratitude even as they are left behind.

The biography reframes Pooh as a cultural phenomenon anchored in a man of contradictions. Milne’s success as a storyteller who created a world that has endured for nearly a century sits alongside a life defined by loss, dissonant family ties and moral tensions. Brandreth’s reporting weaves a timeline from Milne’s early life through his wartime service, the rise of Pooh’s worldwide fame, and the quiet aftermath in which a son and father struggled to reconcile memory with reality. The result is a portrait that invites readers to consider how a single character can both illuminate and obscure the complexities of the creator who gave it life.

As Pooh remains a beloved fixture of children’s literature, Brandreth’s exploration of Milne’s private world asks readers to acknowledge the fullness of a life that produced both warmth and unease. The book does not seek to tarnish a child’s universe but to illuminate the conditions under which it was born, including the pressures of fame, the weight of parental expectations and the personal costs of a life lived in public view. The legacy of Winnie-the-Pooh, the author suggests, is inseparable from the man who imagined it—a man who, like his most enduring character, carried both light and shadow as part of his identity.

The public’s fascination with the Pooh corpus continues to shape how Milne is remembered. Brandreth’s work adds a necessary dimension to that memory by detailing the emotional terrain that underpinned the creation of the stories and the decades of life that followed. It is a reminder that the most enduring children’s literature often rests on a more complicated human foundation than the stories may reveal at first glance. Milne’s life, with its mix of tenderness, struggle and artistry, remains a study in how a creator’s inner life can coexist with a work that has become a global symbol of innocence and wonder. The portrait also raises questions about how the legacies of writers are curated when their personal lives diverge from the public’s memory of their most cherished creations.

In the end, the story Brandreth tells is not simply a cautionary tale about fame or a sanitized history of a beloved character. It is a nuanced account of a man who used his craft to capture the moment, and whose life, like Pooh’s adventures, moved through both bright hours and difficult nights. Christopher Robin’s late reflections about memory—and his concession that we cannot change the past—offer a quiet closing chord: the world might remember Winnie-the-Pooh, but the human story behind it remains a work in progress, inviting further scrutiny, empathy and understanding as new readers discover the bear who made an imprint on popular culture that endures to this day.