Colleges teach words are violence — creating more of the real thing

Survey data portrays rising self-censorship on campuses and a widening view that some forms of speech deserve suppression, with potential implications for free expression and campus culture.

A new FIRE survey highlights a climate on college campuses where some students view shouting down speakers and even the use of violence as acceptable to deter unwanted ideas. The latest rankings place Columbia and Barnard at the bottom among American universities for free expression, with NYU also near the back of the pack. The findings come as debates over safe spaces, trigger warnings and protest tactics continue to roil campus life, raising questions about how institutions balance protection from harm with the principles of open inquiry.

According to FIRE's latest ranking, Columbia sits 256th and Barnard 257th out of more than 200 institutions for free expression, with NYU at 250th. On whether shouting down a campus speaker is acceptable, 74% of Columbia students and 78% of Barnard students said yes. More alarmingly, 26% of Columbia students, 33% at Barnard and 29% at NYU said violence is acceptable in some cases to prevent someone from speaking on campus. In small but notable shares, 2% of Columbia students, 1% at Barnard and 4% at NYU said violence is always acceptable. Taken together, the survey implies that thousands of students at Manhattan's major private universities believe physical violence could be justified to silence speech.

Self-censorship is also widespread. FIRE's data show that more than 60% of Columbia and Barnard students self-censor at least once or twice a month, a pattern some observers describe as a chill that stifles dissent and reshapes academic life. The numbers underscore a campus climate in which fear of reputational damage, social media scrutiny and potential professional consequences influence what students say in class and at events.

Analysts point to what some scholars call 'concept creep'—the expansion of what counts as violence or trauma. Nick Haslam, a psychology professor at the University of Melbourne, notes that the boundaries between physical harm and psychological discomfort have blurred. The framing in some campus discourse treats even non-physical injuries or social discomfort as harms that require protection or redress, a shift that critics say risks diluting the idea of real violence. The discussion extends to how trauma is defined; once it is stretched to include everyday disappointments, supporters worry the term loses its force when applied to extreme harm.

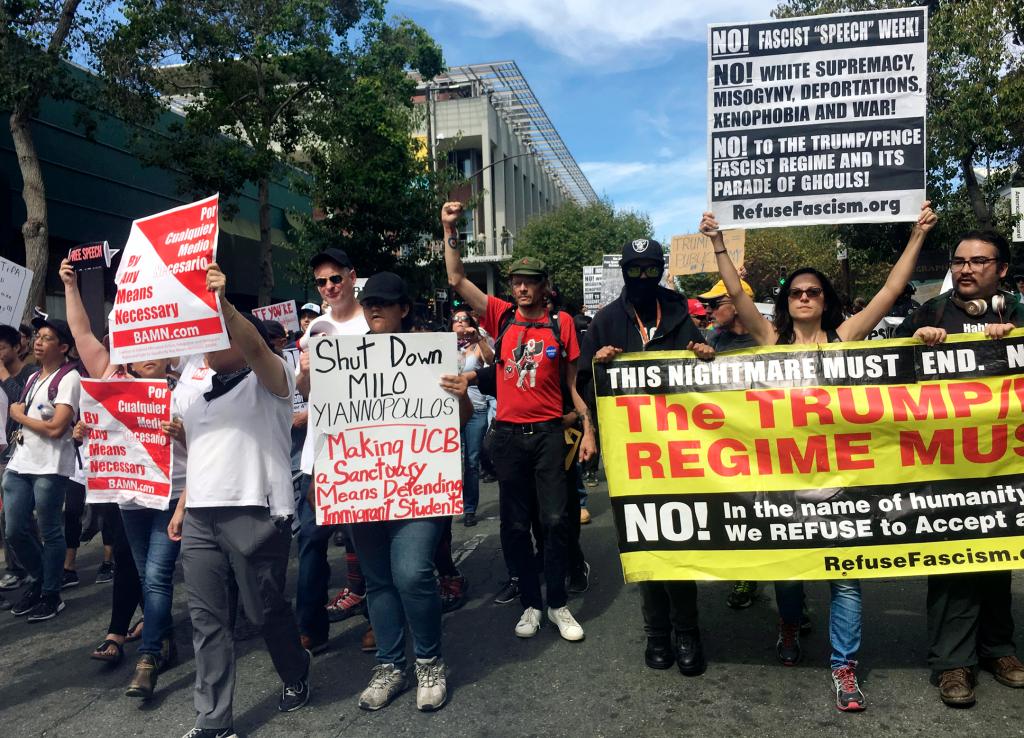

The piece also draws lines to historical parallels, arguing that redefining violence as a form of speech can feed a cycle of intimidation. In campus discourse, references to extremist or totalitarian figures have appeared in teach-ins and student group materials; some coalitions have been cited as praising Mao, Lenin and Hezbollah. Critics say such rhetoric mirrors earlier episodes in which groups claim moral legitimacy and silence dissent through fear. The notes describe these episodes as evidence of a broader trend toward treating ideological opponents as moral enemies rather than as debate partners.

Experts warn that when words are treated as violence, institutions risk normalizing actual force. The column emphasizes the danger of a culture in which disagreement is equated with harm, potentially justifying coercive or violent responses. The overarching argument is that if the boundary between speech and harm becomes elastic, the public may lose sight of the difference between protecting individuals from abuse and protecting the marketplace of ideas from suppression.

Culture and entertainment outlets continue to grapple with these tensions as campuses evolve into stages for protests, performances and panel discussions where the line between dialogue and disruption can blur. The FIRE findings underscore a broader cultural moment in which civil debate and safety concerns intersect, with consequences that extend beyond the campus quad.