Debt, a Gift and a Reckoning: A Personal Essay on Compulsive Buying

A Washington, D.C.–based writer chronicles a cycle of shopping addiction, a transformative gift, and the broader rise in consumer debt.

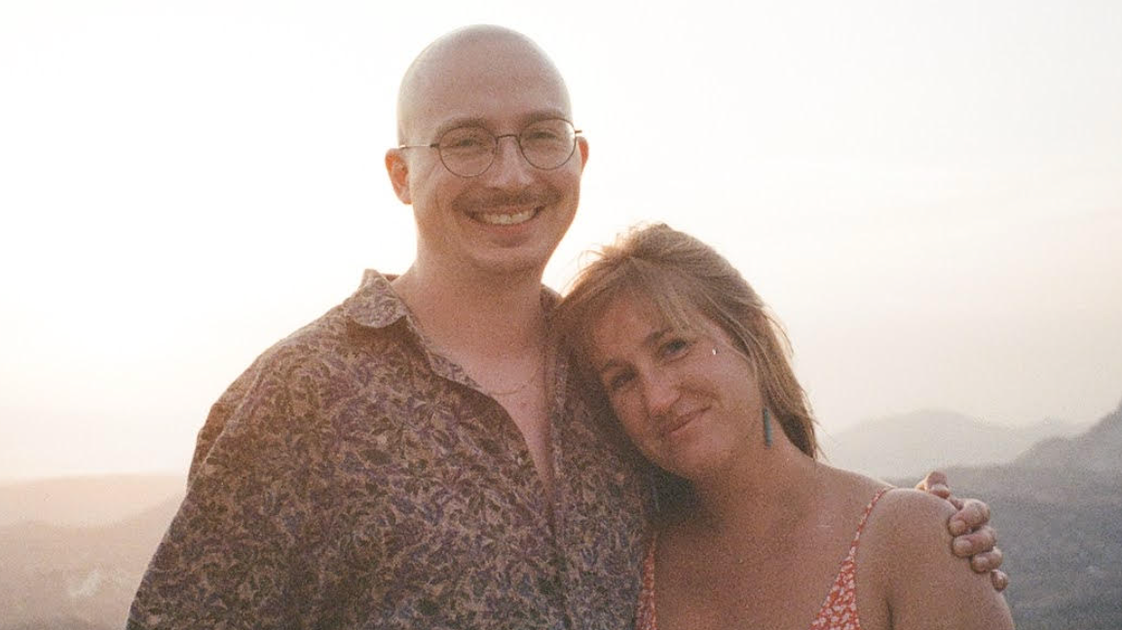

Madison Chapman’s HuffPost personal essay opens with a confession that reads like a cautionary tale about the lure of shopping and the cost of debt. A federal worker who has fought for years to gain financial independence, Chapman describes a cycle that began in adolescence and culminated in a decision that tested the limits of trust within a marriage. A financial advisor’s warning about the long shadow of interest on her ballooning credit-card balances becomes the backdrop for a more intimate reckoning: a fiancé offers a substantial gift, and the response to that gift will become a turning point in her life.

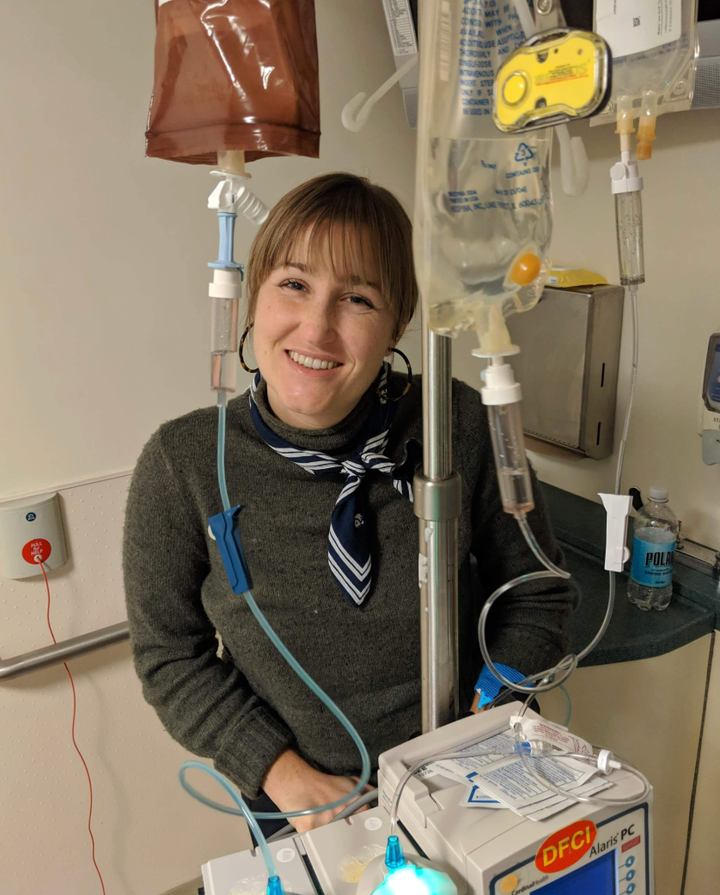

Chapman, who writes from the nation’s capital and identifies as a cancer survivor, says she has long used shopping as a coping mechanism. The story traces a pattern that started with small acts of theft from her mother’s dresser—an early taste of the thrill of getting away with something—then escalated into a habit of buying discount clothes and vintage home decor. Those purchases, she recalls, provided a fleeting sense of control amid a life that felt precarious in ways money could not fix. The larger context is stark: Black Friday online shopping broke records, inflation remained stubborn, and Americans faced a consumer landscape that encouraged more spending even as debt burdens rose. As Chapman writes, the national climate was mirrored in her own life: a $10,000 debt that loomed over her ability to save for major milestones like a house or a family, and the nagging sense that the stuff bought to feel better only deepened the void.

In the years that followed, the debt problem evolved into a shared crisis only when Chapman’s fiancé stepped in with a plan to reset their finances. After meeting with a financial advisor, the couple faced a difficult truth: her spending had not only threatened their financial security but also undermined the trust required to build a life together. The advisor’s phrase—“There’s good debt and bad debt”—took on a new weight when her fiancé transferred $10,000 into Chapman’s bank account, followed by another $10,000 earmarked for emergencies. The gesture offered relief in the moment, but it also created a boundary-testing dynamic in their relationship as they prepared for marriage and the prospect of joint finances.

Chapman’s narrative moves from personal memoir into a broader examination of how debt intersects with health, relationships, and the American economy. The essay references national data that underscore a pattern: consumer spending remains elevated even as households shoulder unprecedented levels of debt. Since Thanksgiving, Americans have spent more than $44.2 billion online, and total online holiday purchases have contributed to a projected year-end spending total that could surpass the trillion-dollar mark. The magnitude of debt is not just a number on a page; Chapman frames it as a lived reality: a collective $1.23 trillion in credit card balances nationwide, with many households relying on “survival debt” to make ends meet. The article notes that nearly half of Americans are contending with these pressures, from childcare costs to housing and groceries, in an economy that has tightened credit in many corners while offering tantalizingly easy ways to borrow.

The midsection of Chapman’s piece shifts to a personal turning point: a joint checking account and a mutual commitment to transparency. After a cancer diagnosis and treatment that left her physically and emotionally drained, she and her fiancé—now her husband—began weekly money chats, and she began inputting every dollar spent into an online tracker. The goal was not merely to curb spending but to rebuild trust and to reclaim a sense of autonomy within a shared life. The couple’s plan reflected a broader philosophy: that accountability in a relationship can be a powerful antidote to the isolation that often accompanies financial struggles. The essay notes that the process was not linear. Even as remission from cancer offered a chance to rebuild, the same underlying impulse that had driven her to purchase as a coping mechanism persisted. A relapse in spending coincided with stress and the residual trauma of illness, and Chapman describes a phase in which she found herself back in the cycle of impulsive purchases and late-night online shopping.

The relationship’s test came into sharp relief when Chapman’s husband confronted the breach of trust head-on. He told her plainly that while he trusted her as a person, his trust on a financial issue had eroded: “No, on money, you’ve completely lost my trust.” The moment underscored a core tension in the piece: love and partnership can withstand danger and betrayal, but money can threaten the foundation of a life together. Chapman writes about the psychological toll of the relapse—the sense that online algorithms and targeted advertising were turning the couple’s shared life into a stage for compulsive urges. In therapy, with a device to block certain apps and a stricter approach to digital marketing, she began a deliberate process of reframing self-care. She paused credit cards, lived with tighter budgets, and learned to buy less—and to buy more intentionally.

In the months that followed, Chapman’s commitment to change grew into a sustainable practice. She sold off old clothing, shopped her own closet, and shifted to debit to avoid the slide of credit. A daily check of her bank account became a ritual, a way to counter the impulse to spend. She used a $100-a-month “treat fund” to maintain a sense of reward without the danger of tipping back into debt. In a notable milestone, her credit cards were paid off, a moment she frames not merely as financial victory but as a restoration of self-worth and partnership. She notes an evolving mindset: the things she had bought to feel better about herself—even when they seemed to improve her life in small ways—were not essential to her happiness. The true currency, she suggests, lies in honesty, gratitude, and time spent with loved ones.

Chapman reflects on the privileges that enabled her to climb out of debt: a stable job, a partner with income sufficient to cover most of her needs, and access to support systems—including therapy and financial counseling—that helped her address the underlying issues behind compulsive shopping. She acknowledges that not all Americans are so fortunate. The essay draws attention to broader economic realities: rising housing costs, stagnant wage growth, and a health-care system where subsidies are set to expire this month, potentially increasing premiums for millions relying on the Affordable Care Act marketplace. For many, even as debt burdens persist, access to basic necessities becomes a major challenge. The piece also highlights systemic concerns, including predatory lending and uneven regulatory oversight that allows high-interest rates and junk fees to persist across state lines.

Despite the hardships described, Chapman closes with a message of resilience and practical steps. She emphasizes that recovery is not a one-time victory but an ongoing effort that requires vigilance, boundaries, and a recalibration of values. The narrative ends on a personal note about a recent date night spent at a bustling holiday market. She and her husband walked through stalls under string lights, but she reports no urge to charge purchases; instead, she reached for her husband’s hand. The concluding line reinforces a core theme: the most meaningful forms of “value” come from relationships, health, and the ability to live with honesty and integrity.

This holiday season, Chapman says she will set spending limits and favor experiential gifts that can be savored and shared. She plans to channel her energy toward time with loved ones and self-care practices that do not require material consumption. The broader takeaway from her story is not merely a cautionary tale about debt but a case study in confronting an addictive behavior with professional help, transparent communication, and sustainable budgeting. Her experience offers a window into how individuals can reorient their lives around what they truly value—honesty, gratitude, and the relationships that sustain them—while acknowledging the ongoing challenges faced by many Americans in a high-debt economy.

In a final reflection, Chapman underscores that her debt, while real, is also a lens on privilege and responsibility. Her journey from a pattern of compulsive spending to a disciplined, mindful approach to money is framed as a personal victory and a shared one with her husband. The piece closes with a sense of cautious optimism: by embracing delayed gratification and refocusing on non-material forms of well-being, she believes she can maintain financial health without sacrificing the things that truly matter.

Madison Chapman is a writer and cancer survivor based in Washington, D.C. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, TIME, Outside, and elsewhere.