Peacemaker: Thant Myint-U’s portrait of U Thant and the Cold War’s quiet broker

A brisk, human portrait of the Burmese diplomat who steered the United Nations through the 1960s and kept the world from tipping into nuclear catastrophe

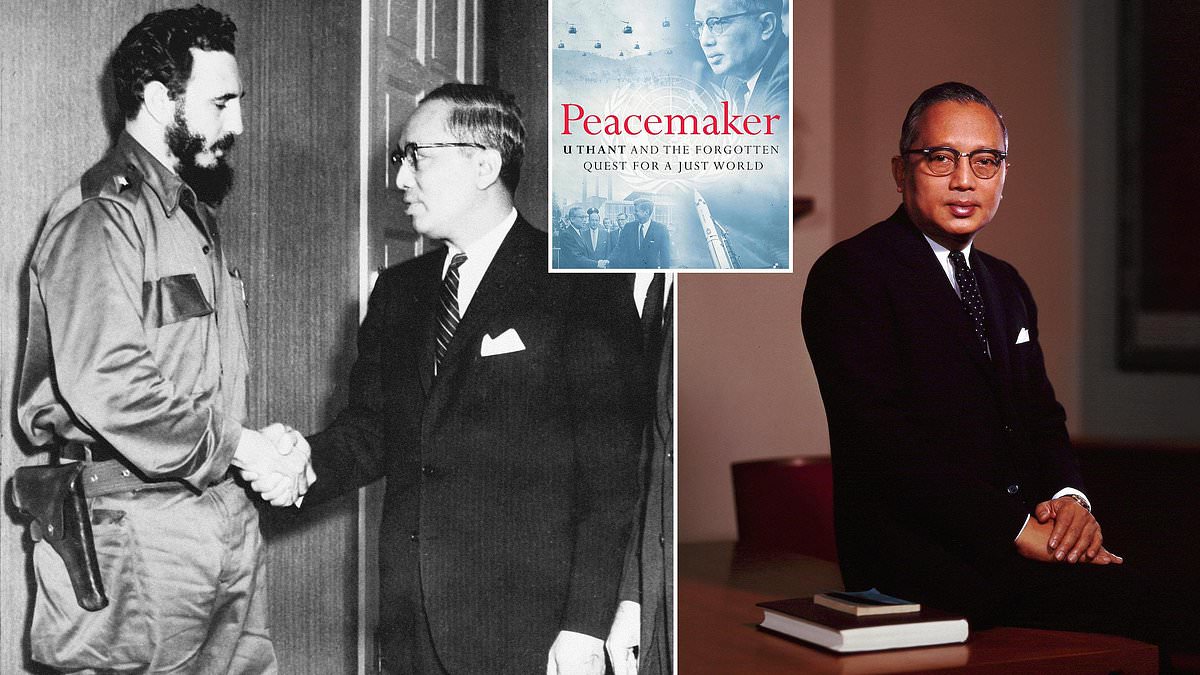

A brisk and accessible biography, Peacemaker: U Thant, the United Nations, and the Untold Story of the 1960s, by Thant Myint-U, looks beyond the headlines to chronicle the decade when U Thant, Burma’s soft-spoken secretary-general, became one of the era’s most influential global mediators. The book, published by Atlantic Books at £22 and running 384 pages, frames Thant as more than a crisis manager. He was a sober, pragmatic diplomat who helped steer the United Nations through some of the Cold War’s sharpest moments and, at times, managed to preserve the idea that the UN could still matter as a forum for calm in an angry world.

Thant’s tenure began in 1961 after the death of Dag Hammarskjöld, and he quickly emerged as the only candidate acceptable to both the Americans and the Soviets as well as to regional powers in the Middle East and beyond. The biography emphasizes the paradox at the heart of his leadership: a man who required quiet, patient diplomacy in a landscape defined by abrupt, high-stakes confrontations. The Cuban Missile Crisis becomes the book’s through-line, with Thant serving as a neutral intermediary who helped frame a path out of a potential catastrophe without either side losing face. His ability to convey a non-denominational message of restraint, while resisting simplistic solutions, is presented as his most consequential achievement.

The narrative also surveys his response to Vietnam, where Thant argued for negotiations with North Vietnam and pressed Washington to acknowledge the limits of what was publicly known about the war. He did not shy away from unpopular stances when he believed they served a larger aim of reducing harm, and his later advocacy for environmental protection signaled a broadening of the UN’s moral horizon as he neared the end of his tenure. The book notes that Thant’s approach was as much about style as substance: a gentle, conservative Buddhist who dressed impeccably, cultivated a measured public persona, and hosted convivial lunches that were almost ritual in their formality and generosity. A tailor’s magazine once declared him the most elegant world leader, a label he wore with quiet humor even as he faced relentless global crises.

The author draws on a brisk, accessible mix of archival material and personal recollections to sketch Thant’s private world. The anecdote-laden portrait includes episodes that humanize a figure often perceived through the lens of international diplomacy: his dry wit, his habit of mixing formal diplomacy with familial tragedy, and his capacity for persistence in the face of stubborn political obstacles. Thant and his wife endured personal losses—one child died in infancy and another died in 1962 after a fall from a moving bus—an arc that the biography presents to underscore the personal cost of public duty. The queen’s first audience with Thant in 1962, recounted with a sense of restrained emotion, is shown as a moment of private tenderness amid the public drama surrounding the UN’s leadership during a tumultuous era.

In addressing the geopolitical tapestry of the 1960s, the book places a pronounced emphasis on Thant’s push for de-escalation in crisis moments. The Cuban Missile Crisis episode is foregrounded as a point at which Thant’s quiet diplomacy translated into concrete steps that averted a nuclear exchange, and his problem-solving approach is shown to rely on a patient, data-informed insistence that the truth be faced by all sides. The biography also highlights his involvement in disputes such as the Congo and Kashmir, where he sought to broker cease-fires and open channels to dialogue even when those efforts exposed him to significant pressure from member states. The Six-Day War of 1967 further tests the limits of UN diplomacy as Thant advocated for a peace process grounded in a withdrawal to pre-war lines, a stance that did not always align with the prevailing momentum among powerful states.

The portrait of U Thant is complemented by a sense of the man’s humanity and the culture of the UN at the height of its early ambitions. The narrative captures his preference for calm, orderly routines—lunches that resembled small, convivial forums where ideas could be tested and tensions attenuated. It also reveals the friction that can accompany grand diplomacy: Thant’s insistence on transparency and negotiation often clashed with political agendas back in Washington and in Moscow, and he sometimes found himself at odds with colleagues who were more media-averse or who believed in a more forceful assertion of national interests.

A recurring thread in the book is the extent to which Thant’s personal philosophy—an emphasis on human dignity, restraint, and collective security—shaped his responses to crises. The biography situates his environmental advocacy toward the end of his tenure as part of a broader shift in the UN’s perception of its responsibilities to future generations. While the work is not hagiographic, it acknowledges Thant’s capacity to blend idealism with pragmatism, a combination that allowed him to navigate the era’s moral and strategic complexities without surrendering the core aim of reducing suffering and preventing escalation.

The book’s tone is brisk and clear, prioritizing the arc of diplomacy over exhaustive backstories, but it does not sugarcoat the limits of Thant’s influence. The review notes that Thant’s optimism about a more cooperative world gradually gave way to the sobering realities of great-power competition and regional conflicts that would continue to define the late 20th century. By the time Thant retired in 1971, the UN could point to a few concrete gains, but the broader wish that the organization would mature into a robust “world security system” remained unfulfilled. Thant died in 1974, and his funeral in Rangoon became a flashpoint amid political tensions at home, underscoring the paradox at the heart of his legacy: a life devoted to peaceful resolution ended against a backdrop of unrest and political upheaval.

Overall, Peacemaker is described as a compelling, if sometimes sobering, homage to a diplomat whose calm, methodical approach helped navigate an era defined by crisis. It offers readers a vivid sense of the man behind the title and of the moral seriousness with which he approached a world that often demanded more than it gave. For readers drawn to history that reads like a well-paced narrative and to portraits of public figures who influenced the course of international affairs, the book provides a nuanced reminder that the UN’s early years were as much about human temperament as geopolitical strategy.