Seymour Hersh on government secrecy in Netflix’s Cover-Up: a life told through investigative reporting

The Netflix documentary examines the Pulitzer-winning journalist’s career from My Lai to Abu Ghraib, highlighting his methods and the enduring value of investigative reporting.

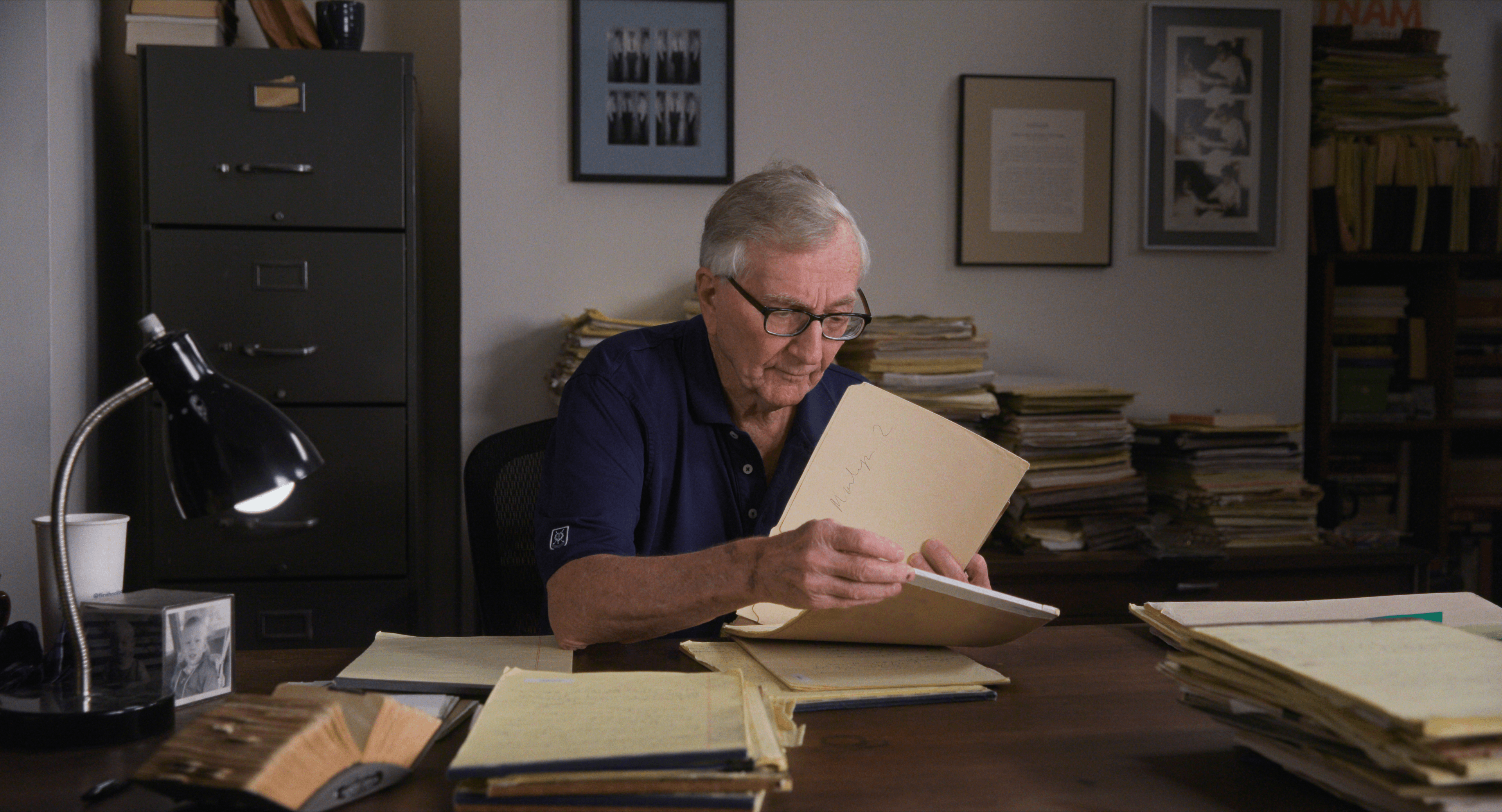

A Netflix documentary about Seymour Hersh, the Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist, centers on the 88-year-old as the subject of an interview in Cover-Up, which premieres Dec. 26. Directed by Mark Obenhaus and Laura Poitras, the film surveys Hersh’s decades of reporting for the Associated Press, the New York Times and The New Yorker, and the stories that exposed government cover-ups from the Vietnam War to the Iraq War. Hersh paused his Substack work to share years of reporting files with the filmmakers, who also feature his editors, co-writers and fact-checkers discussing his process.

A Chicago native, Hersh grew up helping his father run a laundry and dry cleaning business. An English teacher at a two-year college urged him to apply to the University of Chicago, where he learned about a now defunct local wire service, City News. After a stint in the paper’s mailroom and a spell as a police reporter, Hersh says he “fell in love with being a reporter,” a passion he says trained him to see tyranny up close and fueled a career built on dogged pursuit of untold details.

The film places Hersh’s reporting in the context of a broader history of American investigative journalism. It highlights his breakthrough in 1969 with a Dispatch News Service investigation that detailed the My Lai Massacre and the Army’s attempt to cover it up. A mother whose son was among those killed is quoted in the film, underscoring the emotional stakes of uncovering official missteps. The piece helped galvanize the anti-war movement and earned the 1970 Pulitzer Prize for international reporting. The film also traces his 1974 New York Times investigation into the CIA’s domestic spying program, which contributed to the Rockefeller Commission and the Church Committee’s exposure of illegal surveillance practices. Hersh’s work sits alongside the era’s other landmark investigations that reshaped public understanding of government power.

In the documentary, viewers see how Hersh obtained access to sensitive information through patient, sometimes nerve-racking sourcing. Many of his most influential reports began with cold calls and long walks through the Pentagon as a reporter for the AP. As a former Army reservist, he would engage young officers in casual conversations about football to earn their trust and encourage them to speak more openly. The film notes that his meticulous approach sometimes meant he grew tense when a source might be identified on a document, underscoring the fragile line between truth and exposure. Co-director Laura Poitras emphasizes that protecting sources was a central discipline in Hersh’s work and a core part of his reporting ethos.

A key moment in Cover-Up concerns one of Hersh’s sources, Camille Lo Sapio, who provided photographs from Abu Ghraib showing detainee abuse. Sapio describes showing Hersh the images in a restaurant booth on a laptop while her daughter was deployed. She recalls being reluctant at first but ultimately deciding to share the material because she believed the world needed to see the truth. “If there hadn’t been photographs, no story,” Hersh is heard saying in the documentary, highlighting the pivotal role images can play in investigative reporting.

The film also delves into Hersh’s personal life and the support system that sustained him through difficult assignments. He credits his wife, Elizabeth Klein, a psychoanalyst, with helping him navigate moments when reporting on brutal topics threatened to overwhelm him. Though she isn’t interviewed in the film, Hersh recalls a moment when he called from a payphone in distress while working on a harrowing assignment and she reassured him that the story did not reflect on his family. “I married the right person who can calm me down and keep me from going into total despair because I was writing such terrible stuff,” he says.

As Cover-Up concludes, Hersh reflects on why he remains relentlessly focused on exposing cover-ups at age 88. He explains that a country cannot endure without accountability, a conviction he continues to pursue with the help of an editor and a fact-checker on his Substack platform. The filmmakers frame the documentary as a broader appeal to the public and to funders of journalism: the value of investigative work, the necessity of a skeptical journalistic class, and the importance of digging beyond the official record to uncover truths that may be concealed.

Obenhaus describes the film’s aim as twofold: to remind audiences of the importance of investigative journalism and to illustrate how a disciplined, skeptical approach to reporting can reveal truths that institutions may wish to keep hidden. In an era when questions about “fake news” and media credibility dominate discourse, Cover-Up presents Hersh’s decades-long career as a case study in rigorous reporting and responsible journalism. The documentary invites viewers to consider the role of journalism in a functioning democracy and challenges a new generation of reporters to persevere in the pursuit of truth.

The film’s release underscores the continuing relevance of Hersh’s work and the broader vocation of investigative reporting. By weaving together his landmark scoops, the challenges of sourcing sensitive material, and the personal cost of pursuing truth, Cover-Up aims to illustrate not just a single journalist’s career, but the enduring need for questions to be asked, records to be scrutinized, and power to be held to account.