Supreme Court Leaves Llano County Book-Ban Case Behind, Prompting Fears of a New Era

Critics warn that the denial to hear the case could empower state and local authorities to remove books, expanding censorship beyond a few states.

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court’s decision not to hear Leila Green Little et al. v. Llano County leaves intact a Fifth Circuit ruling that could allow state and local governments in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas to decide which materials are accessible in public libraries and schools. Critics say the move signals a broader willingness to permit bans and questions the reach of First Amendment protections beyond those states. Advocates emphasize that the issue hinges on how communities determine access to literature and information.

By denying certiorari, the justices did not rule on the merits of the case; they simply declined to hear it, leaving the circuit-level ruling in place. The court’s action does not resolve the underlying legal questions about censorship, but it does foreclose a national review that could have set a broader precedent. Legal observers say the decision effectively preserves a framework that local authorities in parts of the country can use to remove or restrict books from public shelves and school libraries, potentially widening the scope of materials deemed inappropriate.

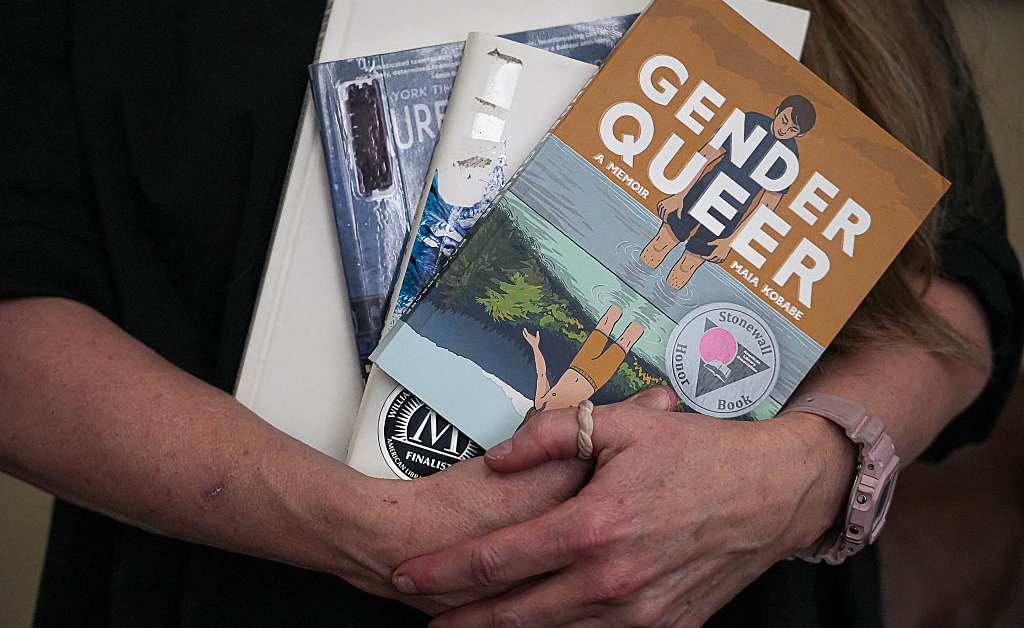

Advocacy groups cite stark nationwide data to illustrate the scale of the trend. PEN America counted 6,870 instances of book bans last school year and counted 156 challenges five years earlier, a surge that underscores the volume and persistence of attempts to remove materials tied to race, gender, and sexuality. The numbers reflect organized campaigns that reach across state lines and are propelled by coalitions that activists say operate in both red and blue states. Critics warn that while the battles may appear local, they are part of a coordinated effort to curb reading and shape what young people are allowed to learn.

Two librarians in Louisiana and Texas described the tension on the shelves and in the staff offices. They said librarians may be the last line of defense in many communities, and that some colleagues have lost their jobs for refusing to pull titles. They portray the fight as less about protecting children than about controlling what people can read and how history is presented. In their view, the approach to removing books is not a local quirk but a nationwide stress test of civil liberties, with zoning patterns in rural areas serving as testing grounds for more aggressive approaches elsewhere.

The ongoing push is connected to a broader national movement led in part by groups such as Moms for Liberty, which organizers say seeks to empower parents and communities to challenge what is taught in schools and what appears on library shelves. The effort has been documented in The Librarians, a documentary by Kim A. Snyder that follows librarians as they navigate calls to remove books from libraries and schools. The film weaves together multiple perspectives and presents the campaigns as part of a coordinated strategy, with screenings held in cities from Dallas to Des Moines, Shreveport, and Anchorage.

Audiences at many screenings have expressed concern about access to literature and the future of the right to read. Prominent messages from organizers and participants emphasize local action: speak up at community meetings, vote in local elections, and if no candidate reflects one’s values, consider running for a school or library board. The organizers say the fight over books is not a distant issue but one that can arrive at a district near readers’ doors, and they urge vigilance and participation to protect reading freedoms for all.

An editorial accompanying the film argues that the drive to remove titles dealing with race, racism, gender, and sexuality is about more than parental control; it is a broader attempt to erase experiences and reshape historical understanding. The piece cites a long arc of censorship in American history and calls for continued engagement to defend the First Amendment guarantees that underpin the right to read. The authors close by invoking President Eisenhower’s admonition against censorship and urging citizens to stay vigilant and engaged, reminding readers that libraries are core to democratic participation.

As debates over book access continue, observers say the immediate legal question remains unresolved, but the practical impact is already being felt in school and public libraries across the country. With the Supreme Court declining to intervene, advocates for reading freedom stress that the fight will persist at the local level, where community standards and elected officials shape what is available on library shelves. In this moment, librarians, educators, parents, and readers are urged to stay informed, participate in governance, and defend the principle that access to diverse books is fundamental to a healthy democracy.