Ten Books That Defined 2025: A Year of Charm, Risk, and Digital Reflection

A diverse year in culture and literature yielded reissues, bold new voices, and works that probe memory, technology, and society.

A year in books closes with a diverse slate of titles that blend intimate voice with bold experimentation, a mix of reissues and first-person narratives that push readers to see the world through new angles. Vox Culture’s annual roundup of the 10 best books of 2025 highlights works across fiction, memoir, graphic narrative, and critical writing, signaling a year when literary form kept expanding even as familiar themes persisted. At the top of the list is Raja the Gullible, a title that has already earned the National Book Award and has been praised for its warmth, humor, and human-scale storytelling as it threads personal memory into a broader regional history. The book follows Raja, a 63-year-old gay English teacher living in Beirut, who finds himself offered a writing residency in America on the strength of a single earlier book. The narrative voice moves with ease between domestic scenes and the larger shadows of Beirut’s history, from the civil war through the 2019 economic collapse, the Covid years, and the 2020 port explosion. The author’s prose is buoyant yet perceptive, managing to be both humane and slyly witty about the traumas that shape Raja’s life and his relationship with his overbearing mother, a figure who resists being relegated to mere parenthesis in his storytelling. This book is described as a treat from start to finish, a testament to how memory and place can coexist with humor and tenderness in a novel that feels deeply alive on every page.

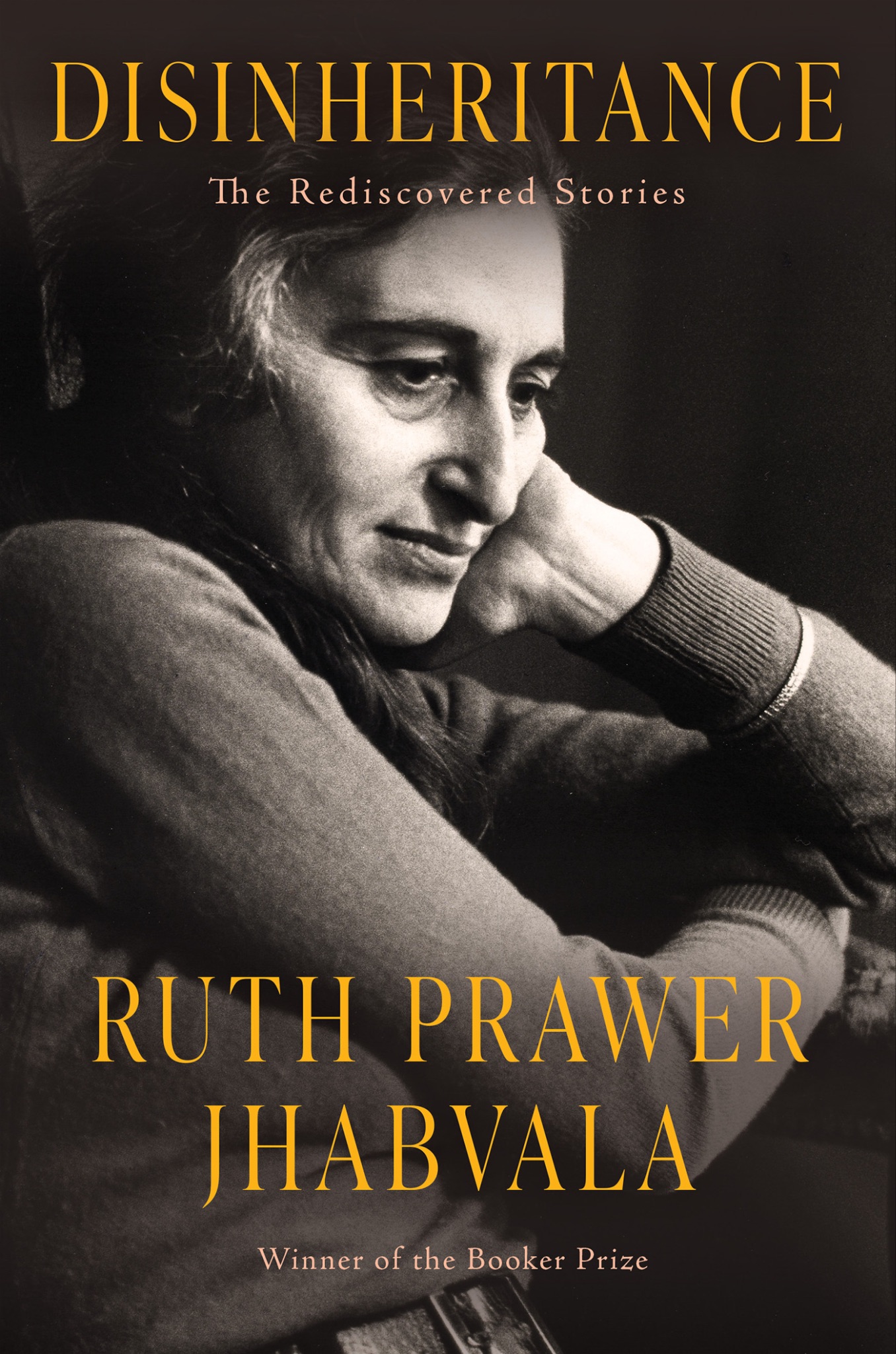

Disinheritance by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala collects stories that feel almost ceremonial in their measured, affectless surface, while beneath the polish there is a sharp, corrosive intelligence about marriage, class, and the strain of tradition. Jhabvala, who lived through upheaval across England, India, and New York, writes from a position of exile that remains intimate rather than aloof. In the collection, a suite of English and Indian lives unfolds with a quiet intensity: couples maneuver around the expectations of family, societal proprieties, and the stubborn pull of desire. The prose is compact, almost diagnostic in its clarity, yet the stories land with a strange beauty that can feel both cool and unsettled. The book invites readers to consider how cultural distances and miscommunications shape relationships across borders and generations, and it does so with a precise, sometimes biting, humor that never sacrifices humanity for critique.

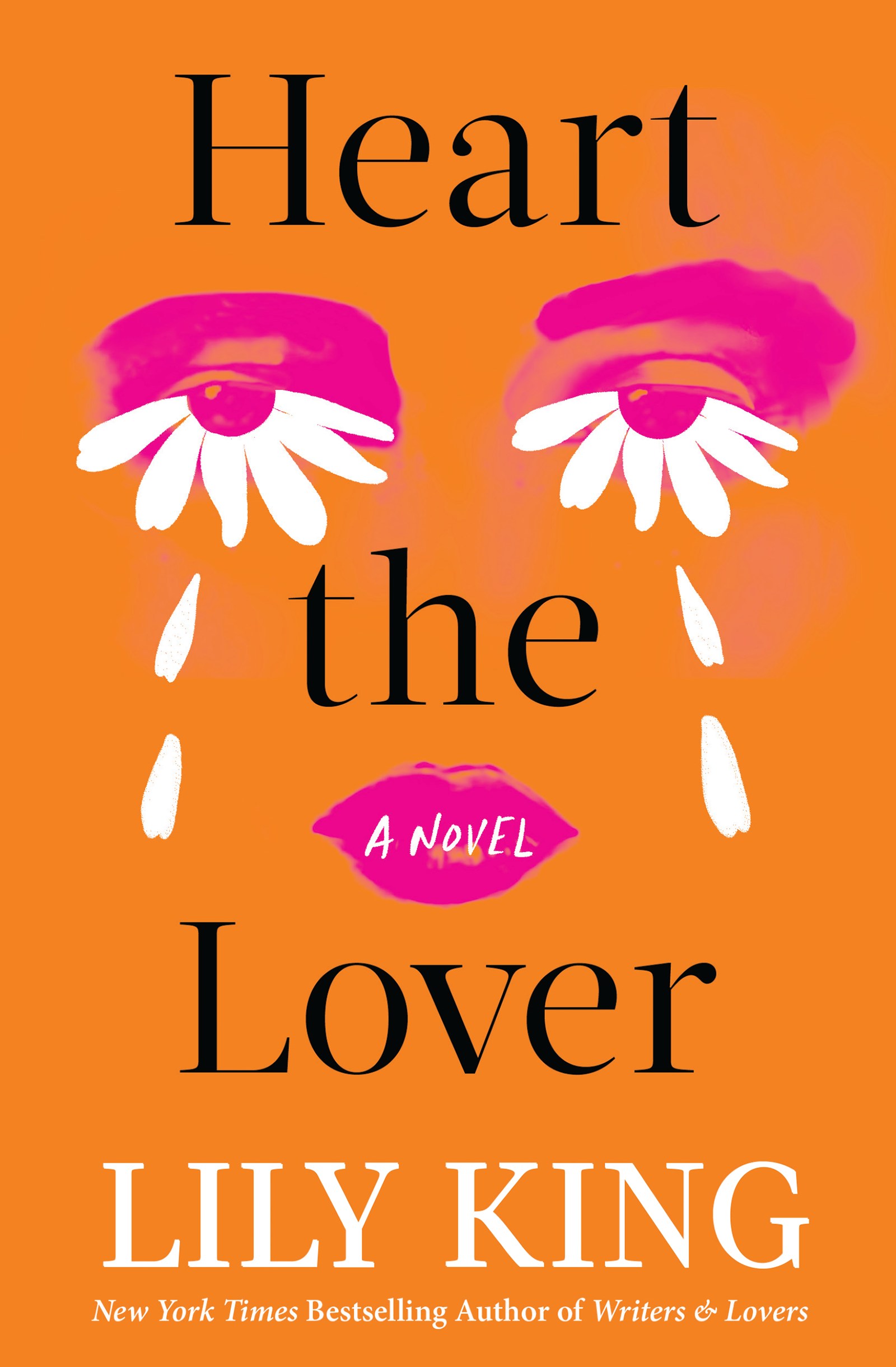

Heart the Lover, Lily King’s expansive new novel, is described as an immersive, sometimes overwhelming experience that can feel like living inside a story for days at a time. A companion to her earlier Writers and Lovers, this work stands on its own with two halves: a feverish 1980s college love triangle and, decades later, a hospital-room reunion that digs into longing and regret. King is lauded for her precise, intimate rendering of young love and the way memory refracts across time. The result is a novel that is both combustible and deeply human, anchored by characters whose stubbornness, tenderness, and stubborn hopes feel recognizably true. The book’s momentum comes from its concrete details—the classroom conspiracies, the shy glances, the found moments of intimacy—that suspend the reader in a world where love’s first bloom and later disillusionment sit side by side.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, long celebrated as a tonic of wit and mischief, has been reissued by Modern Library as a reminder of a certain era’s social frivolity and courage. The diary-style narration follows Lorelei Lee, a flapper who navigates Atlantic crossings and European sojourns on the strength of her own agency and charm. The novel’s charm comes from its deft mix of inevitability and clever self-awareness: Lorelei presents herself as a naive, endearing figure, even as the reader comes to recognize the strategic dexterity that keeps her steps ahead. The reissue is a timely reminder of how a text once deemed a frothy comedy can also function as a crisp commentary on gender, power, and performance—an observation that remains relevant in today’s cultural conversations about agency and consumer spectacle.

What We Can Know by Ian McEwan is a late-entry standout that revisits questions about memory, history, and complicity in a world transformed by climate disaster and pervasive digital life. The narrative unfolds in a 22nd century that has rebuilt civilization after floods, with a scholar named Thomas Metcalfe who becomes obsessed with reconstructing a lost poem from the early 21st century after its original author’s work vanished from public view. McEwan’s voice is characteristically precise, and his speculative setting becomes a vehicle for a meditation on privacy, testimony, and the ethics of historical reconstruction. The book’s third act pivots into a revelation drawn from a manuscript—an audacious tether between past and future that reframes what readers thought they knew about the central mystery and the fragility of memory in our era of data trails and social footprints.

Do Admit! by Mimi Pond takes a more playful tack with a graphic biography that’s both charming and razor-sharp. The Mitford sisters—precocious, audacious, and controversial—are rendered in blue ink with a brisk, cartoonish energy that makes their lives feel almost mythic while preserving the human warmth and sharp edge of their reputations. Pond’s approach blends whimsy with biographical rigor, offering a vivid, modern reading of a century-old story and a reminder that the Mitfords’ public personas still speak to how celebrity, politics, and moral ambiguity intersect. The biography’s humor never masks the historical weight; instead, it allows readers to approach a fraught period through art that is lively and accessible.

The Wild Boy of Aveyron, a 1800 encounter that has long fascinated scientists and philosophers, is revisited in a new light by Roger Shattuck in Victor, a humane, tender account that anchors the famous case to the people who cared for the boy. The book’s focus on relationships rather than spectacle offers a counterpoint to sensational descriptions of “nature versus nurture.” Shattuck’s treatment emphasizes how crucial social bonding is to human development, suggesting that a man’s humanity may be defined as much by his bonds as by his abilities or whether he speaks. The narrative invites readers to reflect on the era’s scientific ambitions and the intimate lives that shaped their interpretations, framing the wild boy’s story as a lens on how society treats vulnerability and difference.

Vera, or Faith by Gary Shteyngart continues the author’s tradition of blending dystopian critique with personal, intimate storytelling. Set in a post-democracy United States, the novel follows Vera, a precocious, anxious 10-year-old grappling with questions of identity, family, and belonging in a world where surveillance, social control, and propaganda have become quotidian. Shteyngart’s humor and sharp social observation illuminate the pressures on young people to perform in a political landscape that often leaves them exposed. Vera’s voice—fierce, funny, sometimes rueful—drives a story that feels both intimate and urgent, a reminder that even in bleak futures, human resilience and curiosity endure.

Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor centers a single Manhattan summer around Wyeth, a young Black painter whose work intersects with questions of representation, race, and artistic ambition in an era of social upheaval. The novel follows Wyeth as he navigates love, ambition, and the pressures of being seen in a city that rarely stops watching. Taylor’s sentences are described as elegant and precise, and the book balances a quiet emotional core with an exploration of art’s role in political life. It is a meditation on how art can both reflect and complicate the moment it inhabits, offering readers a portrait of making meaning through creative practice in a time of collective reckoning.

The final entry, Searches by Vauhini Vara, presents a hybrid inquiry into the rise of artificial intelligence and the tech-industrial complex that now informs daily life. Vara’s book blends memoir, reportage, and speculative inquiry as she navigates Google, Facebook, Amazon, and OpenAI, reflecting on what these platforms have given and what they have taken from us. The narrative also examines how memory, privacy, and human connection are reshaped by algorithms and corporate power. In a notable twist, Vara threads chapters through ChatGPT responses, asking the artificial intelligence to critique its own rhetorical strategies. The result is a thoughtful, lucid meditation on the terms of human-technology interaction and a timely reminder of the ethical considerations that will shape our digital future.

Taken together, these 10 titles map a year that felt both intimate and expansive: novels and memoirs that zoom in on personal relationships, as well as books that widen the lens to ask how technology, memory, and history shape collective life. The mix of reissued classics and bold new works reflects ongoing conversations about how literature can hold memory while probing upheaval, and how graphic narratives can sharpen perception just as prose can pierce to the heart of shared experience. Among the year’s most resonant themes are the fragility and resilience of human bonds, the power of art to illuminate or subvert social norms, and the way modern life—whether Beirut’s war-torn streets, a stalled democracy, or the algorithmic infrastructure of everyday life—continues to press in on individual lives in ways that demand new forms of storytelling.

In reviewing this year’s list, critics note that the best books of 2025 do not simply imitate past successes; instead they expand the vocabulary of what a novel, a memoir, or a graphic biography can do. They invite readers to dwell with complex characters whose lives illuminate larger forces, and to consider how memory and imagination can coexist with critical scrutiny of the present. From the intimate hilarity of Raja the Gullible to the speculative, morally charged wonder of What We Can Know, the collection signals a robust moment for culture and entertainment that rewards both rereading and discovery. The year’s best books ask hard questions about who we are, how we tell our stories, and what we owe to one another as readers, citizens, and fellow humans navigating a rapidly changing world. The reading public can look forward to revisiting these titles in libraries, on personal shelves, and in conversations that will carry their ideas well into 2026 and beyond.