Very cool: The 70s Afro-rock Zamrock genre enjoying a surprising rebirth

Zamrock’s psychedelic blend fuels a renewed global interest, led by Sampa the Great and a new generation of artists and collectors

Zamrock, the 1970s Afro-rock movement born in a newly independent Zambia, is making a global comeback as new artists, collectors, and audiences rediscover its bold fusion of psychedelia and traditional Zambian sounds.

In its heyday, Zamrock emerged amid Zambia’s post-colonial optimism and a government policy that prized local music. Radio stations were required to play mostly Zambian-origin tracks, creating a bustling, homegrown scene. Bands such as WITCH, Amanaz, and Ngozi Family built a reputation for high-energy live shows and fearless experimentation. The movement blended fuzzed guitars with pounding rhythms and traditional chants, producing a sound that felt both revolutionary and deeply African. Yet by the end of the 1970s, Zamrock faltered as copper prices fell, recording infrastructures faltered, and piracy and an HIV/AIDS crisis took a heavy toll on musicians. Five of WITCH’s founding members died from AIDS, and the scene largely faded from the global map.

The revival began in earnest in the 2010s, driven by Western record-curation labels and a renewed fascination with the genre’s exuberant energy. Now-Again Records, based in the United States, played a pivotal role, including compiling and reissuing Zamrock material and helping spur a broader rediscovery. Egon Alapatt, Now-Again’s founder, has said he wasn’t sure there would be a market for Zamrock, but believed there would be curiosity: “If I’m curious about this, there’s probably other people who are curious about this.” The buzz among vinyl collectors surged as original Zamrock discs—rare and pressed in small quantities—began fetching high prices on the resale market. In Lusaka, Time Machine proprietor Duncan Sodala recalls seeing original records selling for hundreds of dollars as interest grew globally.

In parallel, Zamrock’s original bands began re-emerging. WITCH, short for We Intend To Cause Havoc, reformed with Jagari Chanda, the band’s frontman, and Patrick Mwondela, alongside a rotating group of European musicians. The revived outfit has toured beyond Africa, releasing new material and drawing crowds at major stages such as Glastonbury. “It’s like a new lease on life I never expected at my advanced age,” 74-year-old Jagari said during a stop on the 2025 world tour, noting the Munich crowd surfing that he had never experienced before.

The Zamrock revival has also intersected with contemporary pop and hip-hop. Zambian-born, Botswanan-raised rapper Sampa the Great has explicitly referenced Zamrock as a source of “post-colonial” identity and a bold, liberated sound. While drafting her third studio album, she looked to Zamrock’s brief but potent flame as a blueprint for a fearless voice. “We were looking for a sound and a voice that was so post-colonial. And Zamrock was that sound — that sound of new freedom, that sound of boldness,” she told the BBC. Her single Can’t Hold Us features fuzz guitars and a defiant flow anchored in Zamrock’s spirit, signaling a shift toward what she describes as “nu Zamrock.” Tembo, who has performed at prestigious venues like Glastonbury and the Sydney Opera House, says the new project will run Zamrock across the album while blending hip-hop and other influences.

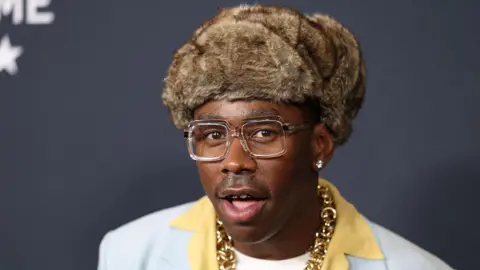

Beyond Sampa, a new generation of artists—both in Zambia and abroad—have mined Zamrock’s DNA. US artists such as Travis Scott, Yves Tumour, and Tyler, the Creator have sampled tracks from Ngozi Family, Amanaz, and WITCH, helping the genre reach new listeners who may never have encountered it from its original era. The cross-pollination isn’t limited to sampling; Zamrock tracks have appeared on popular television soundtracks, including HBO’s Watchmen and Apple TV+’s Ted Lasso, introducing the sound to audiences who might otherwise overlook it. Third Man Records, co-owned by Jack White, has released live WITCH material, further embedding Zamrock in the broader rock ecosystem.

There is broad consensus that Zamrock’s resurgence owes much to a sense of exuberance and authenticity. Egon Alapatt argues that the music’s English-language accessibility helped it circulate internationally, while Duncan Sodala emphasizes its perceived innocence and genuineness. “There was a tremendous bias amongst collectors of rock and roll music from around the world against music in the native language of the country that it was created,” Egon has observed, pointing to a curious early barrier that a new generation is now overcoming. Sodala adds that the music’s sincerity resonates with listeners: “I think people listen to it and feel how genuine it is.” Yet both men caution that Zamrock should not be reduced to a mere database of samples; the artists and their origins remain central to its ongoing story.

In Zambia, the revival has also taken root locally. Lusaka’s Bo’jangles venue hosts a Zamrock Festival annually, now in its third edition, while Modzi Arts—a cultural hub in the capital—hosts a small Zamrock museum that preserves posters, recordings, and instruments from the era. Sampa the Great has underscored that her forthcoming album, while deeply informed by Zamrock, will push forward with intents that honor the original musicians and ensure their stories remain visible in the newer music landscape. The broader Zambian scene—vivid with artists like Stasis Prey, Vivo, and Mag 44, a Sampa collaborator—continues to experiment with Zamrock’s language, blending it with hip-hop, R&B, and other genres to reflect contemporary life.

Glastonbury’s reception of WITCH and other Zamrock acts has helped propel the movement onto global stages. Jagari notes that the crowds, diverse in age and origin, embody the music’s universal appeal. “In Munich, there was crowd surfing, which I had never done before,” he recalled during a tour stop. For Sampa and others, the key is to ensure Zamrock’s roots are acknowledged. “There is a fear that if we are not loud about Zamrock’s origins, we may be taken out of the equation,” Sodala said. “Sampa is very important because she doesn’t want Zamrock to be known just for the samples.”

The Zamrock story is both a testament to resilience and a cautionary tale about cultural memory. While the original scene faced structural challenges—economic volatility, piracy, and health crises—the revival is buoyed by a new economy of streaming, cross-continental collaborations, and a renewed appetite for world music with a rock edge. The genre’s current wave is not merely nostalgia; it is about reimagining the past in a way that speaks to contemporary listeners while preserving the people and places that gave Zamrock its distinctive voice.

As Sampa the Great and Jagari continue to carry Zamrock into new arenas, the question becomes how best to balance innovation with origin. The consensus among fans and industry observers is cautiously optimistic: Zamrock’s energy, its fusion of African rhythm and Western rock, and its celebratory spirit offer a template for musical intercultural exchange that stays true to its Za mbian roots while expanding its global reach. The fire that Jagari sees lit in 2025 is not a spark to be contained; it is a flame meant to be fed by the next generation of musicians, listeners, and curators who will keep Zamrock burning for years to come.