Who Belongs Here? From Zoot Suits to MacArthur Park in the Belonging Debate

A Culture & Entertainment look at how history mirrors today’s enforcement tactics and the enduring question of who counts as American.

On July 7, 2025, armored vehicles rolled into MacArthur Park in Los Angeles as children attended summer camps. National Guard troops deployed alongside federal agents on horseback, a tableau described by many witnesses as a war zone. Community health workers providing routine medical services scattered in fear. Mayor Karen Bass, who confronted the agents at the scene, called it "a city under siege." Across the summer, ICE raids swept through Home Depot parking lots, car washes, bus stops, and farms across Los Angeles County, targeting people who looked like they could be undocumented. Appearance alone was used to warrant probable cause. In September, the Supreme Court formally cleared the way for agents to profile people based on their race. The fear forced people to stay home; businesses shuttered; parents kept their children home from buses or familiar streets. By October 14, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors declared a state of emergency.

Scholars and community organizers describe the events as a modern echo of a centuries‑old question about who belongs in America. The visible enforcement unfolded against a backdrop of a borderland history in which immigrant, Indigenous, and mixed‑heritage communities have repeatedly claimed space in American life even as they have been told to stay invisible. The Zoot Suit Riots of 1943 offered an early, brutal template: Mexican American youths wearing zoot suits—an exuberant symbol of identity—were assaulted in the streets as public panic framed them as outsiders. The riots occurred at a moment when the nation was at war and Japanese Americans were interned in camps nationwide; the era fused fashion, race, and policy into a blunt message: you don’t belong here.

Those attacked in 1943 were often not recent immigrants but families with roots in Los Angeles going back generations. The incident exposed how belonging could be contingent on who held power and who was seen as a threat, even as communities persisted and asserted their place in the city’s cultural fabric. The press and police dynamics of the era reinforced a message that was less about law and more about social control. The zoot suit, a garment born from a generation of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx youth blending styles and languages—caló and pachucos—became a symbol of urban American identity. It was also a target. In wartime Los Angeles, with Pearl Harbor still fresh in public memory and with 120,000 Japanese Americans banished to internment camps, paranoia ran deep. The riot was less about clothing than about who could claim American space and who could be treated as if that claim did not exist.

In that broader arc, the question of belonging has repeatedly hinged on who is asked to prove it and how that proof is interpreted. The notes tied to this report emphasize a recurrent pattern: communities with deep roots in the American landscape—many of them citizens by birth or long‑standing residents—are nonetheless treated as perpetual outsiders when political climates shift. The Zoot Suit Riots and the broader history of Mexican American labor and culture show how the country’s self‑image as a nation of immigrants can coexist with moments when belonging is earned through conformity rather than shared citizenship. The contemporary episodes in Los Angeles echo that tension, inviting a reckoning with what it means to be American when enforcement practices disproportionately target people who look like they belong in the country as much as they belong to it.

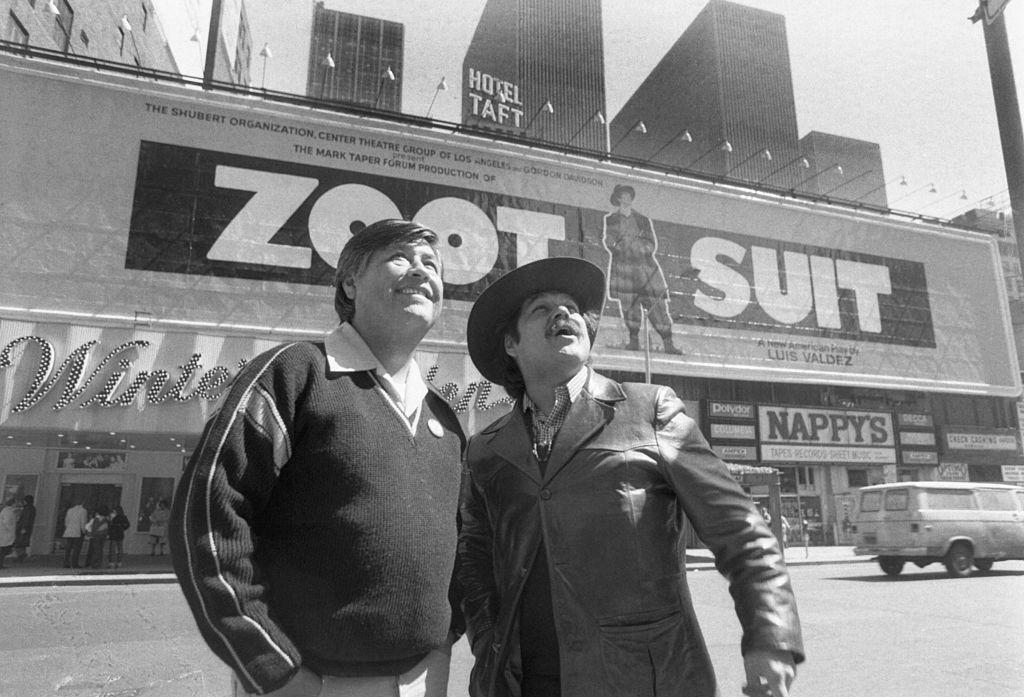

The narrative turns toward culture as a remedy and a record. A handful of passages recount the life and work of Luis Valdez, a pivotal figure who helped fuse theater, labor history, and Latino identity into a public assertion of belonging. Valdez, who rose from the picket lines in the 1960s with Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta to form El Teatro Campesino, used performance to argue that Mexican Americans were not outsiders but necessary narrators of the American story. In 1979 his production Zoot Suit became the first Chicano play to reach Broadway, dramatizing the very events that had once branded Pachuco identity as suspicious. Valdez would later write and direct La Bamba, the 1987 film that brought Latino stories to mainstream Hollywood. Those milestones solidified a counter‑narrative to the idea that heritage must be hidden to belong, insisting instead that culture can be a vehicle for inclusion.

The author’s personal arc intersects with Valdez’s legacy in a way that underscores the piece’s central question: how does a nation define belonging when its own stories are written at the margins? The notes recount growing up in suburban Texas in the 1980s and ’90s, where jokes and stereotypes about Mexican heritage often carried a sting. The writer describes a path back into a sense of identity through community college, filmmaking, and a Hispanic scholarship that introduced the encounter with Valdez. That meeting, and Valdez’s insistence that farmworkers and Mexican Americans were not foreign to America but essential to its character, helped shape a career in documentary storytelling and a broader project of exploring identity, memory, and film as tools of cultural memory.

Valdez’s trajectory—alongside the broader history of the Chicano movement—remains a touchstone for understanding how the culture‑and‑entertainment sector can grapple with the politics of belonging. The image of the Zoot Suit era and the contemporary scenes in Los Angeles converge on one central premise: the identity politics of appearance, language, and heritage have long influenced how Americans define who belongs. The theater, the film, and the streets together tell a story of resilience and protest, of communities refusing to disappear even when political winds push them to the margins. Valdez’s work and its reverberations in contemporary culture offer a template for how the public can reframe questions of belonging from a threat model to a narrative of contribution and rights.

The final reflection in the piece argues that the country’s most enduring question is not about documents or borders but about whether America will honor the promise of equal belonging to all its people. The Zoot Suit Riots showed a time when the social contract was breached; the events in 2025 in Los Angeles illustrate that breach is not merely historical. The author closes with the assertion that the Pachucos belonged in 1943, and the families in MacArthur Park belong in 2025. The country’s future, the piece implies, rests on translating that belonging from a claim into a lived, protected right for every community that has already helped build the United States.