Woody Allen says he never boards a flight without a copy of S. J. Perelman

In a recent interview, the filmmaker details his reading ritual, favorite authors, and a current book on the Third Reich.

Woody Allen has long maintained a personal preflight ritual: he never boards a plane without a copy of the writings of S. J. Perelman. In a recent interview, the director explained that Perelman’s humor and linguistic play keep him engaged and composed when a flight stretches and turbulence rattles the cabin. He also flagged his current reading, Erik Larson’s The Garden of Beasts, a nonfiction look at the rise of the Third Reich and the lead-up to World War II, saying the subject matter continues to fascinate him.

Allen described Perelman as an essential companion on the road, a writer whose wit informs his own approach to storytelling. “Whenever I take a flight, I’m never without a copy of the Perelman collection,” he said, noting that early pleasures included J. D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. He added that, in moments of turbulence, readers might reach for a Bible, but he reaches for Perelman to steady himself and stay mentally engaged.

In a desert-island scenario, Allen said he would want the Perelman collection above all else, a sentiment that underscores how central Perelman’s writing remains to his craft. He has also returned to his interest in prewar history, recounting a lifelong habit of reading widely on the era while acknowledging the mix of nonfiction and fiction that has shaped his own work. He cited favorite writers and titles that have influenced him, from Elie Wiesel and Hannah Arendt to Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying, along with early exposure to Catcher in the Rye. He also said he does not enjoy certain modern, more experimental works that lack a straightforward human narrative, such as some of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake and Ulysses.

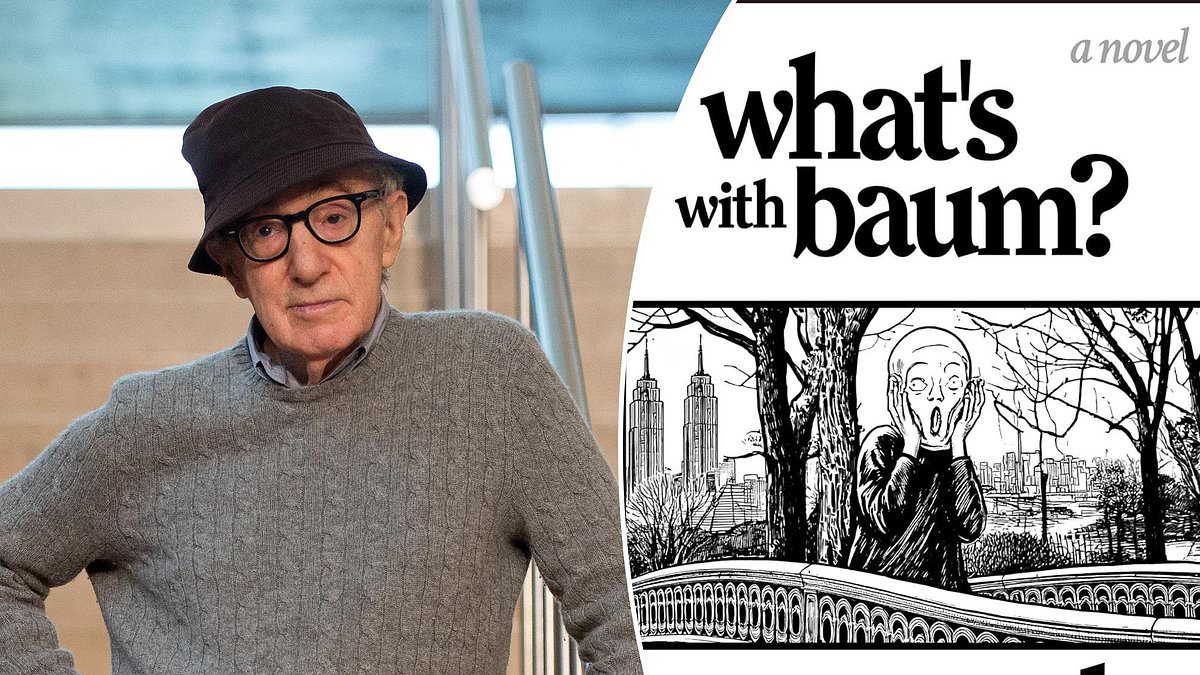

The interview also touched on his public-facing writing project, What’s With Baum? published by Swift Press (£18.99), which is available through outlets including the Mail Bookshop. The conversation paints a portrait of a filmmaker whose relationship with reading spans humor, memory, and a longstanding curiosity about the voices that shaped the modern literary landscape.

Allen’s remarks are part of a broader pattern in which he uses literature as both a shield and a spark—an ongoing preflight ritual and a reservoir for ideas that inform his prolific creative output. The mix of Perelman’s humor, Salinger’s early influence, and a fascination with historical nonfiction reveals a literary palate that travels as readily as his films do, echoing a career built on sharp, literate, and sometimes provocative storytelling.