BBC investigation finds children with cancer exploited by fraudulent crowdfunding campaigns

An international network used emotive videos of seriously ill children to raise donations for treatment, with many families reporting little or no access to the funds.

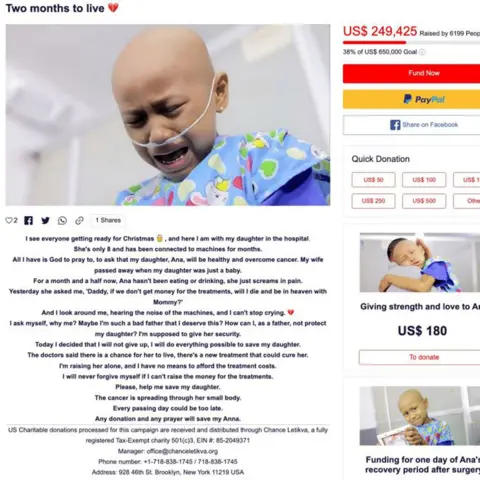

An investigation by BBC World Service has found that desperate families of ill children were exploited by online crowdfunding campaigns that claimed to fund life-saving cancer treatment. The BBC identified 15 families who say the campaigns raised millions in their children’s names, but they received little or no money, and in some cases were unaware the fundraisers existed. Nine families say the campaigns appear to have collected about $4 million (£3.3 million) in total, yet they never received any of the donations.

One of the most documented cases involves Khalil, a seven-year-old from Cebu, Philippines. His mother, Aljin Tabasa, says a local fixer arranged a fundraising video that showed Khalil crying and asked her to shave his head. She says she was paid a $700 filming fee on the day; the video helped raise about $27,000, but she says she received none of the donations and was told the campaign had failed. A year later, Khalil died. BBC findings indicate the video remained online and donations continued to accrue in Khalil’s name, while his family says they received no funds.

Across the world, desperate parents of sick children are being drawn into a pattern: campaigns marketed as charitable drives, run from multiple countries, that promise to cover costly medical care but yield little for the families themselves. Investigators traced campaigns under the banner Chance Letikva (Chance for Hope), registered in Israel and the United States, and linked to other groups such as Walls of Hope and Saint Raphael. The networks sought to identify children described as three to nine years old, with “beautiful” appearances and no hair, according to people involved in recruitment and production.

The BBC’s inquiry began in October 2023 after a distressing YouTube advert drew attention to a girl named Alexandra from Ghana, crying over the cost of her treatments and appearing in a campaign that appeared to raise nearly $700,000 (£523,000). Similar videos from around the world showed a consistent formula: urgent, emotive language, fast fundraising totals, and a sense of time running out. Investigators say the campaigns with the broadest international reach were tied to Chance Letikva, whose directors and intent were difficult to verify. To identify the families, BBC researchers used geolocation, social media signals and facial recognition tools to connect videos to real-life households from Colombia to the Philippines. They also donated small amounts to select campaigns to track how totals changed when donations appeared in the campaign pages.

The investigation describes a network of intermediaries who recruited families and filmed them in hospital settings, sometimes for long hours. In Khalil’s case, Aljin says a man named Rhoie Yncierto arranged the shoot and later denied telling families to shave their children's heads for filming. Yncierto said he had “no control” over how the money was used and did not receive payment for recruiting families. He offered apologies for the families’ feelings but provided no evidence of how funds were allocated. The BBC found no registration link between Rhoie Yncierto and Chance Letikva in the documents it reviewed.

The stories go beyond Khalil. In the Philippines, Aljin Tabasa described a lengthy shoot directed by an operator who traveled from Canada and promised more money if donations grew. The operator, who used the name “Erez,” arranged for a 12-hour shoot and repeatedly asked for retakes. Months later, the family says they were told the video had not performed well, even as the campaign page allegedly collected tens of thousands more. Aljin says she later learned the same campaign remained online and that substantial sums had been raised in Khalil’s name. When BBC researchers confronted Erez Hadari about his role, he argued the organization had never been active, and did not respond to follow-up questions. Documents and interviews linked Hadari to campaigns under Chance Letikva and related entities, including Walls of Hope and Saint Raphael, though none of these organizations acknowledged direct involvement with the specific cases described.

In Ukraine, BBC findings point to Tetiana Khaliavka, who coordinated a shoot with five-year-old Viktoriia, diagnosed with brain cancer, at the Angelholm Clinic in Chernivtsi. Viktoriia’s mother Olena Firsova says she never wrote or spoke the caption shown on a social post promoting the campaign, and she had no idea the video was uploaded. The clinic says it did not authorize filming for any fundraising efforts and subsequently terminated Tetiana’s employment. Nevertheless, Viktoriia’s campaign appears to have raised more than €280,000 (£244,000) online. Contract documents reviewed by the BBC showed an expected payout of $8,000 (£5,986) after fundraising goals were met, but the goal amount was left blank.

Isabel, a mother in Colombia who helped organize one such campaign, told BBC she was approached by someone who claimed to work for an NGO; she said only one campaign she helped publish was released and that it was not successful. Isabel later apologized, saying she would have refused the work had she known what was happening. Ana, who lives in a remote indigenous community in Sucre, told the BBC that the foundation disappeared after her daughter’s brain tumor diagnosis, and that she was told her video was not used and that nothing was done with it, even as records showed the video had been uploaded and fundraising totals continued to rise. In January, Isabel’s account was contradicted by a different set of documents and a separate narration about Ana’s case revealed a discrepancy between what was promised and what was delivered.

The spread of campaigns across borders has prompted scrutiny from regulators. The Israeli Corporations Authority says it could bar a founder from working in the nonprofit sector if there is evidence of illicit activity or use of entities as a cover for wrongdoing. In the United Kingdom, the Charity Commission advises potential donors to verify that the charity is registered and to contact the appropriate fundraising regulator if in doubt. The BBC asked Chance Letikva, Walls of Hope, Saint Raphael, Little Angels and Saint Teresa for responses; none replied.

Some families say the absence of funds has compounded the trauma of their child’s illness. Olena Firsova, Viktoriia’s mother, told BBC researchers she felt “sickened” by the findings and described the concept of money being raised in the name of her daughter as “blood money.” The BBC provided families with contact requests for the involved campaigns and organizations, and the participants were given opportunities to respond. Several said they preferred not to comment or could not be reached.

The BBC’s investigation underscores a troubling pattern in international fundraising where high-pressure, emotionally charged campaigns leveraging vulnerable families and their children can be difficult to monitor across borders. Experts caution that charitable giving requires due diligence: donors should verify charity registrations, review how funds are allocated, and be wary of campaigns that promise rapid, extraordinary results or ask for ongoing sponsorships without clear accountability. The report also highlights how quickly a video designed to elicit sympathy can be weaponized to raise money and how challenging it can be for families to track a share of funds once a campaign is published online.

For families confronted with a child’s illness, the emotional toll of such exploitation adds to the medical burden. Olena’s reflection in the Ukraine case, and Aljin’s account in the Philippines, illustrate the lasting impact when families discover that the money raised in their child’s name may not have been used for treatment as promised. The BBC’s reporting team continues to pursue additional information and seeks responses from the organizations and individuals named in this investigation. If you have information to add, they urged, contact simi@bbc.co.uk.