Resident doctors in England strike over pay and conditions as NHS winter pressures mount

England’s resident doctors walk out for five days this December amid a dispute over real-term pay, while the government says it has offered the largest public-sector pay rise in years and aims to expand specialist training posts.

England’s resident doctors are set to strike for five days, from 07:00 GMT on Wednesday, 17 December, to 07:00 GMT on Monday, 22 December, in a dispute over pay and working conditions that comes as NHS hospitals brace for the winter surge in flu and other infections.

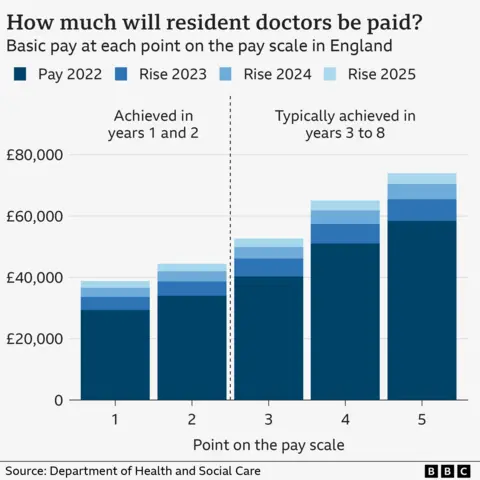

Resident doctors — the group formerly known as junior doctors — are qualified physicians who have completed a medical degree and are in post-graduate training that often leads to specialization. They make up roughly half of NHS doctors and work across the NHS from emergency departments to GP practices. In September 2024, the government announced a name change to reflect their growing level of expertise. Pay for those in the first post-degree foundation year starts at about £38,831, rising to about £44,439 in the second year, with extra payments for night shifts and other long or unsocial hours. After eight years or more, salaries can reach around £73,000. The past two years have seen substantial pay increases — 22% in 2023–24 and a further 5.4% in 2025 — though the strike continues to draw attention to the broader question of real‑term value.

The BMA says resident doctors’ pay is around 20% lower in real terms than it was in 2008, even after the 2025 rise. The government uses the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) to measure inflation for public sector pay, while doctors say student‑loan interest is calculated with the higher RPI measure. Analysis from the Nuffield Trust indicates pay has fallen about 5% since 2008 if CPI is used, but roughly 20% if RPI is used, underscoring the disputed basis for calculating earnings.

The government’s latest response frames the offer as a significant consolidation of gains. Health Secretary Wes Streeting has said resident doctors have received the largest pay rises of any public-sector group over the past three years and that the government will not offer further increases. Instead, the deal focuses on expanding the pipeline of specialist training posts, which resident doctors enter in their third year of training. In 2025, there were more than 30,000 applicants for about 10,000 posts — including many from abroad — and the government said it would add 4,000 more posts by 2028, with the first 1,000 available from 2026. The package also included emergency legislation to prioritise appointments for doctors who studied and trained in the UK and reaffirmed an offer to cover costs such as exam fees.

Responding to the offer, Dr. Jack Fletcher, chair of the BMA’s resident doctors committee, said it did not restore pay and amounted to little change in the broader remuneration framework. An online poll conducted in the days ahead of the strike showed 83% of respondents supported continuing industrial action, with a turnout of 65%. Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer said he was gutted by the result, calling it irresponsible given the NHS pressures from flu and other winter infections. The BMA’s current mandate for industrial action runs out in early January, and the union has begun asking members whether to extend the dispute.

The strike comes amid ongoing winter pressures. NHS leaders have urged patients not to delay seeking care and to attend appointments unless contacted, while stressing that those with life‑threatening conditions should call 999 or go to an emergency department if needed. For urgent, non‑life‑threatening issues, the NHS 111 online service or helpline remains available, and GP surgeries are expected to operate as usual. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are not affected by this walkout.

Public-sector pay has provided some context around the broader trend. In May 2025, the government announced pay rises for a range of public-sector workers, including 4% for other doctors and teachers in England and prison officers, 3.6% for some NHS staff in England (including nurses and midwives), and 3.25% for civil servants, illustrating a wider pattern of targeted uplift alongside departmental negotiations.

The BMA says the dispute is about more than headline numbers: resident doctors often have substantial student debt and limited control over where and when they work, and many must relocate for training, which can impose additional costs. The union has underscored the need for pay that reflects the length and cost of medical training and the broader financial commitments faced by graduates.

Looking ahead, the balance of negotiations rests on both the government’s willingness to adjust terms and the BMA’s decision on whether to extend industrial action beyond January if a satisfactory agreement is not reached. In the meantime, NHS trusts are preparing for continued disruption, even as they work to protect emergency services and essential care for those with urgent needs during a peak season for respiratory illness.

There is also context from broader public-sector pay rounds. May 2025 brought across-the-board rises for several worker groups, illustrating how policy makers balance public services’ winter demands with labor-market pressures. The evolving landscape means resident doctors’ pay remains a flashpoint in a wider conversation about NHS staffing, funding and the ability to deliver care during a period of high demand.

The dispute’s next steps will depend on forthcoming negotiations and how long the health system can absorb the disruption without compromising patient safety. As hospitals navigate the balance between keeping services running and honoring the strike, the ultimate outcome will hinge on whether new terms can satisfy the BMA without triggering further rounds of industrial action in the months ahead.