UK cold-weather health alerts: how the system works and what it means for health services

Amber and yellow warnings issued across much of England signal heightened risks as temperatures fall, guiding NHS and government responses.

Public health officials in the United Kingdom are issuing cold-weather health alerts as winter temperatures push health risks higher. Amber and yellow alerts have already been issued across much of England, signaling that the cold could threaten vulnerable people and place pressure on health services. The alert system is designed to combine weather forecasts with health risk assessments to guide preparations and responses at national and local levels.

The alerts are run jointly by the UK Health Security Agency and the Met Office, and they cover the cold season from November 1 to March 30. A separate heat-health alert runs from June 1 to September 30. The system issues warnings to the public and distributes guidance directly to NHS England, the government and healthcare professionals during periods of adverse weather. Alerts include a headline about expected conditions, details on regional impact, and links to further information and advice.

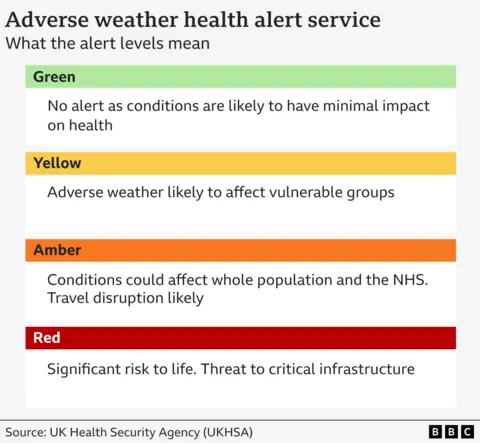

Alerts are categorized into four levels, from green to red, based on Met Office forecasts and data. Green is the baseline, with preparatory advice if temperatures rise or fall. Yellow signals that hot or cold weather could affect those who are most vulnerable, such as older adults or people with preexisting health conditions. Amber indicates a risk that could affect the whole population, with the NHS likely to see increased demand and travel disruption. Red is the most severe level, used when weather poses a life-threatening risk to healthy people and could trigger failures in critical national infrastructure.

Cold weather can worsen illnesses and increase the risk of certain conditions. Flu and other winter illnesses circulate more readily, and pneumonia risk rises after cold spells. A BBC Radio 4 Inside Health segment on the effects of cold on the body highlighted a controlled experiment in which a healthy participant’s body temperature and circulation changed as the air cooled from 21C to 10C. The expert, Prof Damian Bailey of the University of South Wales, described 18C as a tipping point: below that, the body must work harder to keep core temperature, which can strain the heart and circulatory system and raise the risk of heart attack and stroke. When indoor temperatures cannot be kept at 18C, experts advise wearing warm gloves, socks and a hat, adopting a higher-carbohydrate diet, and staying physically active to generate body heat.

Experts also emphasized practical steps for staying safe when heating is limited. Wearing extra layers, keeping bedrooms insulated, and ensuring people at risk have access to warmth and fluids remain central. The alerts are not only about staying warm but about reducing the health burden during colder periods by guiding communities, care services and hospitals in advance planning and response.

Officials say the weather alert service aims to reduce illness and deaths by providing timely information to the public and frontline services. The system coordinates actions across NHS networks and social care to prepare for spikes in demand and to deliver targeted guidance to vulnerable populations on precautions and where to seek help during periods of extreme cold.

As winter continues, authorities stress the importance of forecasts and guidance in safeguarding health, with the system updating alerts as conditions evolve to support health care capacity and community safety.