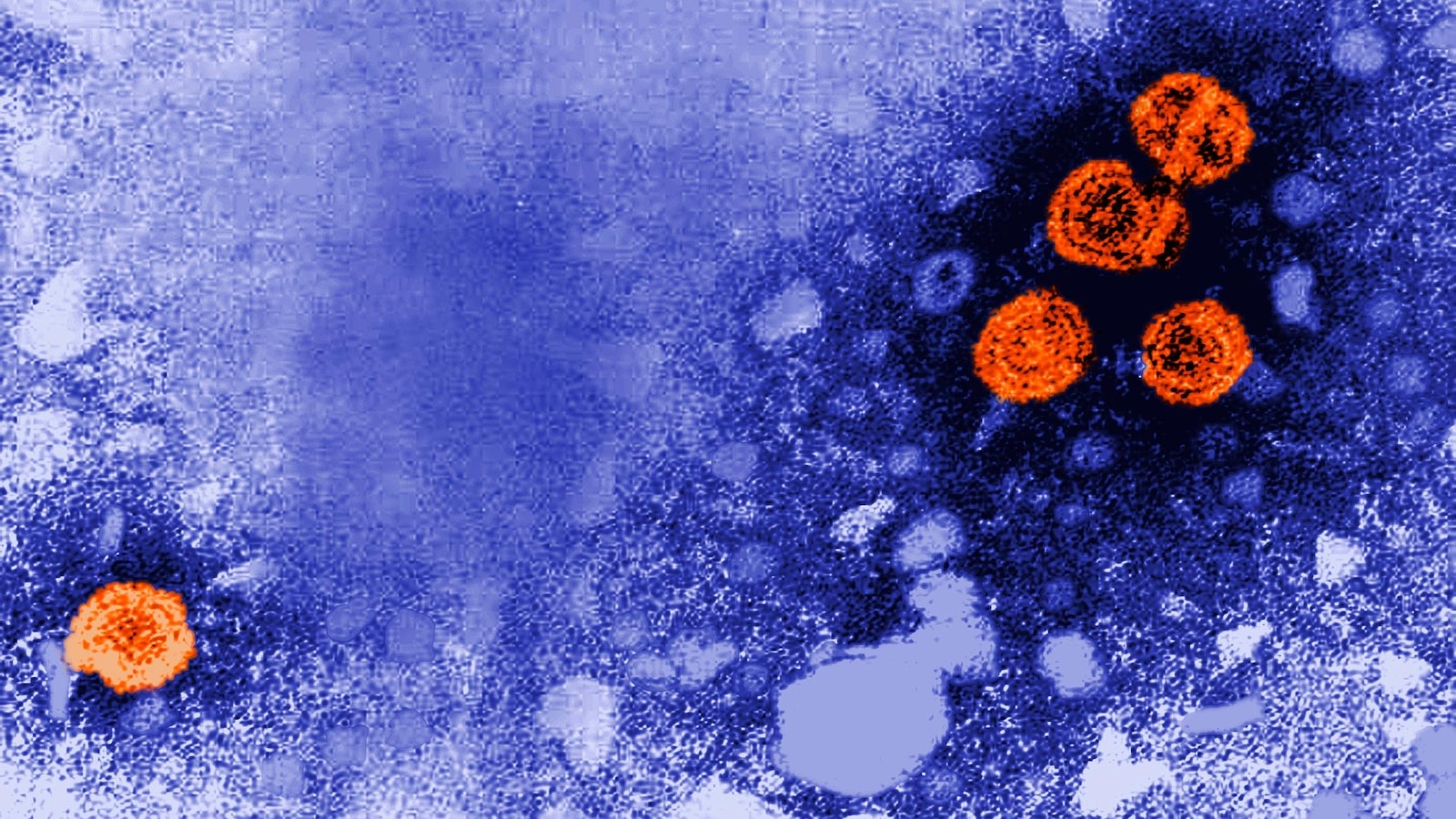

U.S. awards no-bid contract to Danish researchers to study hepatitis B vaccine in African newborns, raising ethical concerns

No-bid grant to a Danish university for a birth-dose hepatitis B study in Guinea-Bissau has sparked questions about ethics reviews, potential harm, and political influence.

The Trump administration has awarded a $1.6 million, no-bid contract to a Danish university to study hepatitis B vaccinations on newborns in Africa, a move that has ignited ethical concerns about withholding vaccines from infants at significant risk of infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention awarded the grant to a team at the University of Southern Denmark, a decision that has drawn scrutiny because the proposal was unsolicited and did not undergo a customary ethics review. Public-health researchers and others have questioned whether the design could put infants at risk and whether political considerations influenced the funding.

The project is set to begin early next year in Guinea-Bissau, an impoverished West African nation where hepatitis B infection is common. Researchers are funded for five years to study 14,000 newborns in what the plan describes as a randomized controlled trial: some infants would receive the birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine at birth, while others would not. Participants will be followed to track death, illness and long-term developmental outcomes. The protocol notes that there is no placebo involved, and the first 500 enrollees will be followed for five years to assess behavior and brain development, while the remainder will be observed for up to two years for shorter-term safety signals.

Advocates of birth-dose vaccination point to decades of evidence showing the vaccine protects newborns from severe liver disease and premature death, arguing that withholding a proven intervention from babies at risk is unethical. Critics, however, say the study’s design—particularly the deliberate withholding of a protective vaccine from some infants—raises concerns about whether the research is acceptable, especially given the vulnerability of the population and the history of consent issues in certain trials.

Dr. Boghuma K. Titanji, an infectious diseases physician at Emory University, described the plan as “unconscionable” and warned that it could fuel vaccine hesitancy in Africa and beyond. “There’s so much potential for this to be a harmful study,” Titanji said, noting the broader public health consequences if communities interpret the research as a statement about the safety or necessity of vaccination.

The research team has asserted that the study received approval from Guinea-Bissau’s national ethics committee, and they say the project represents a rare window of opportunity: Guinea-Bissau does not currently recommend a birth dose, but universal vaccination of newborns is slated to begin in 2027. The team contends that evaluating the birth-dose policy in the context of broader programmatic changes could yield insights for other countries considering similar policies. They emphasized that the trial is designed to measure safety and development over time, with no placebo and with careful monitoring for adverse outcomes.

Despite the team’s assurances, the award invites comparisons to controversial past research. Some public health experts have raised questions about the Bandim Health Project led by Benn and her husband, Peter Aaby, which has faced criticism from other Danish researchers and former public-health officials. Tom Frieden, the former CDC director, has criticized related work by Benn and Aaby as having fundamental methodological flaws in the past. In this latest case, critics say the absence of an external ethics review and the involvement of higher-level funding authorities beyond the CDC raise the stakes and intensify concerns about oversight and accountability.

The funding arrangement itself has drawn attention. A CDC official familiar with the decision described the grant as unsolicited and not routed through the agency’s typical research-funding process. The official said Department of Health and Human Services leadership directed the approval and indicated that special funding would accompany the project, though the exact rationale for bypassing standard reviews was not disclosed publicly. Some CDC staffers reportedly voiced concern in private communications about the award, underscoring a tension between expediency in funding innovative work and the fundamentals of ethical review and transparency.

Public-health advocates acknowledge that the case spotlights challenging questions about research involving disadvantaged populations. They emphasize that the hepatitis B vaccine has a long-standing safety record since its introduction for newborns in the United States in the early 1990s and that global vaccination programs have reduced chronic hepatitis B infections and related liver disease. Yet the debate persists over whether a trial that withholds a proven intervention—even temporarily and within a strictly controlled research setting—can be justified as a means to answer policy questions in another country.

The Guinea-Bissau setting adds another layer of complexity. While the country plans to implement universal birth-dose vaccination in 2027, the current policy does not require a birth dose. Proponents say the study could yield locally relevant data on vaccine impact and developmental outcomes, while opponents argue that the potential for harm to newborns—even if limited to a minority of participants—makes the research ethically questionable, especially given the historical context of medical mistrust in some communities and the risk of stigmatizing groups.

In the broader health community, the CDC has reiterated that it will uphold high scientific and ethical standards in any funded work. The agency’s statement emphasized that the project underwent review at the national ethics body of Guinea-Bissau and that measures are in place to monitor safety and ensure that participants’ welfare remains the priority. Critics say that independent, external ethics review and broader stakeholder engagement are essential when research could affect such a vulnerable population, and they argue that the lack of a formal CDC procurement pathway for unsolicited proposals undermines transparency and governance.

The question of how to balance urgent public-health needs with rigorous safeguards is not new, but the particulars of this case have jolted a sector that is accustomed to long-standing consensus about the value of vaccines. If the study proceeds, researchers will need to demonstrate that the potential benefits—informing policy on birth-dose vaccination and understanding long-term developmental outcomes—outweigh the risks and that any findings will be translated into ethical, policy-laden recommendations that respect the rights and well-being of African babies and their families.

For now, the debate continues among public-health scientists, ethicists, and policymakers about whether this no-bid contract should have been awarded and how oversight should be structured for high-stakes studies conducted across borders. As Guinea-Bissau prepares to update its vaccination policies, the outcome of this inquiry could influence future funding decisions and the way researchers design similar trials in settings with pressing infectious-disease burdens.