America’s most famous unsolved cipher: the Beale papers and a $60 million buried mystery

Only one of three Beale ciphers—decoded using the Declaration of Independence—has been read; two remain unbroken more than 180 years after the alleged burial.

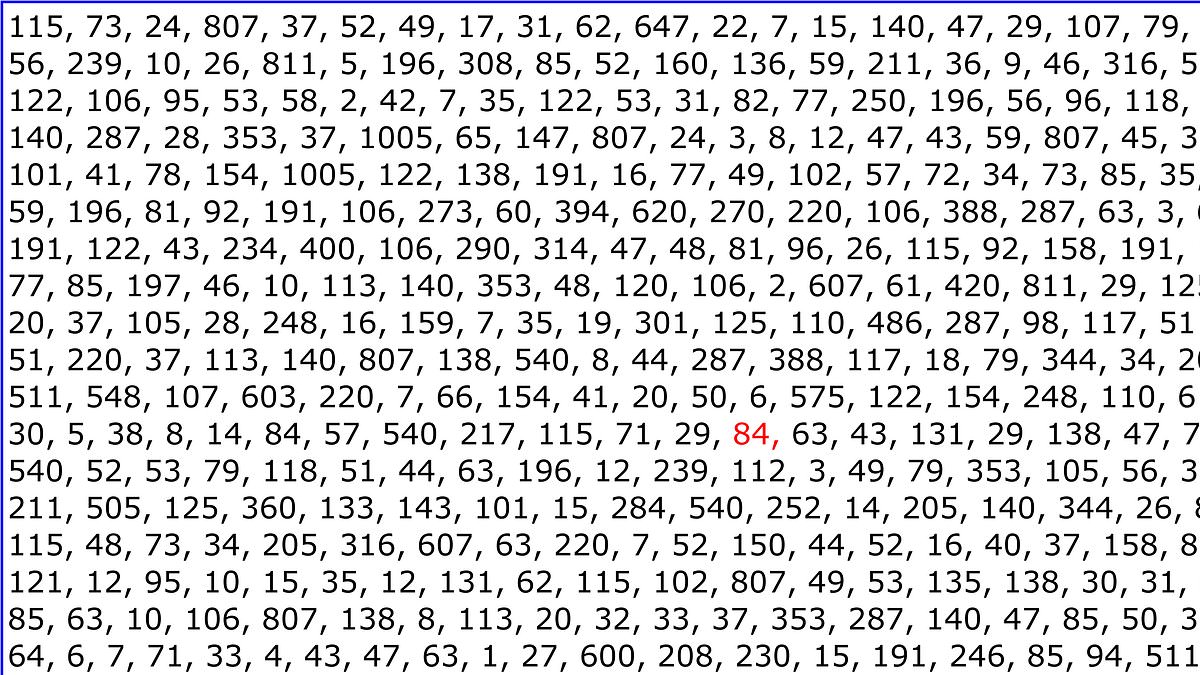

A set of three 19th-century ciphertexts that claim to point to buried treasure worth as much as $60 million remains largely unsolved more than 180 years after the events they describe, cryptology enthusiasts say. The so-called Beale ciphers have attracted amateur and professional attention since a pamphlet containing the three numeric texts was published in 1885; only the second of the three has been credibly deciphered.

The story as presented in the pamphlet begins in the spring of 1822, when a Virginia man identified as Thomas J. Beale left a locked iron box containing "papers of value and importance" with an innkeeper, Robert Morriss. Beale instructed Morriss to hold the box until he returned; according to the account, Beale never did, and Morriss later opened the box 23 years after receiving it. Inside were three pages of numbers that Morriss, and later a friend who devoted decades to the task, could not initially interpret.

The pamphlet, published by James B. Ward as the Beale Papers, records that Morriss’s friend succeeded in cracking the second cipher in the late 19th century by using a textual key: he numbered every word in the Declaration of Independence and mapped each number in the cipher to the first letter of the corresponding word. That decoded text, often called B2, lists the contents of two deposits made in 1819 and 1821, stating quantities of gold and silver and jewels obtained in St. Louis. The solved passage reads in part that the first deposit consisted of "one thousand and fourteen pounds of gold, and three thousand eight hundred and twelve pounds of silver, deposited November, 1819," and that the second deposit included "nineteen hundred and seven pounds of gold, and twelve hundred and eighty-eight pounds of silver; also jewels... valued at $13,000." The pamphlet adds that the treasure was buried in Bedford County, Virginia, "about four miles from Buford's," a reference commonly taken to mean the site of a long-vanished tavern whose chimney remains.

The other two ciphers—known as B1 and B3—are said to contain, respectively, precise burial coordinates and the names and residences of the joint owners who supposedly shared the treasure. Morriss’s friend stopped the search before solving those texts and published his findings and copies of the papers in the Beale Papers, inviting public help in resolving what he called "all that is dark in them." That publication, and the tantalizing values it declared, have spurred recurring waves of interest from hobbyists and professional codebreakers alike.

Cryptanalyst Nick Pelling, who has studied historic ciphers for roughly three decades, told the Daily Mail that at least one of the remaining two ciphers could be solvable. Pelling said sequences produced when applying the same Declaration-of-Independence key to B1 are "too improbable to be random," suggesting a more subtle encryption method may be in play. He warned, however, that the narrative surrounding the papers has been layered over the ciphers by later commentators and promoters, making it hard to separate provenance from folklore.

John Piper, a hobbyist who discovered the Beale papers while traveling, said he became engrossed in the texts and has pursued decoding efforts for years. Piper told the Daily Mail he believes he cracked aspects of the ciphers in 2014 and described the Beale materials as a "layered cipher," with the first two texts potentially read in the same fashion and the third exhibiting additional quirks. He added that such work can consume one’s life and that any claimed solutions would benefit from validation by trained cryptologists.

Scholars and skeptics have long questioned the authenticity of the pamphlet and the veracity of its claims. Modern analyses note inconsistencies in language and provenance, and some researchers consider the Beale Papers a likely hoax or literary fabrication of the late 19th century. The printer and publisher, James B. Ward, presented the typed copies as accurate transcriptions of papers found in the box; his introductory notes framed the material as complete and urged readers to help make light of its mysteries.

Despite skepticism, the Beale ciphers continue to draw attention because the solved second text appears coherent and because the numeric form invites algorithmic and human analysis. Pelling told the Daily Mail that the single practical question is whether the remaining ciphertexts can be broken. "The only question anyone should have is one and only one: can we break the ciphers?" he said, adding that reliance on the surrounding narrative is unwise when attempting decryption.

The Beale story occupies an unusual place at the intersection of cryptography, local history and treasure lore. The combination of a partially solved cipher, a plausible Virginia burial locale, and precise material tallies has encouraged periodic searches and new decoding attempts, even as the authorship and chain of custody of the pamphlet remain contested. The case also illustrates classic cryptanalytic techniques from the 19th century—using a literary text as a key—and the limits of such systems when keys or additional layers of encryption are unknown.

Public fascination shows no sign of abating. Amateur sleuths post theories and proposed solutions online, while a handful of researchers continue to test alternate keys and layered approaches. Until and unless B1 and B3 yield to verifiable decryption or historical documentation proves or disproves the pamphlet’s claims, the Beale ciphers will persist as one of America’s most enduring cryptographic mysteries.