Archaeologists uncover 1,600‑year‑old Christian care facility for the elderly at Hippos

Mosaic inscription reading “Peace be with the elders” and funerary imagery suggest a designated institution for older residents in the Byzantine city near the Sea of Galilee

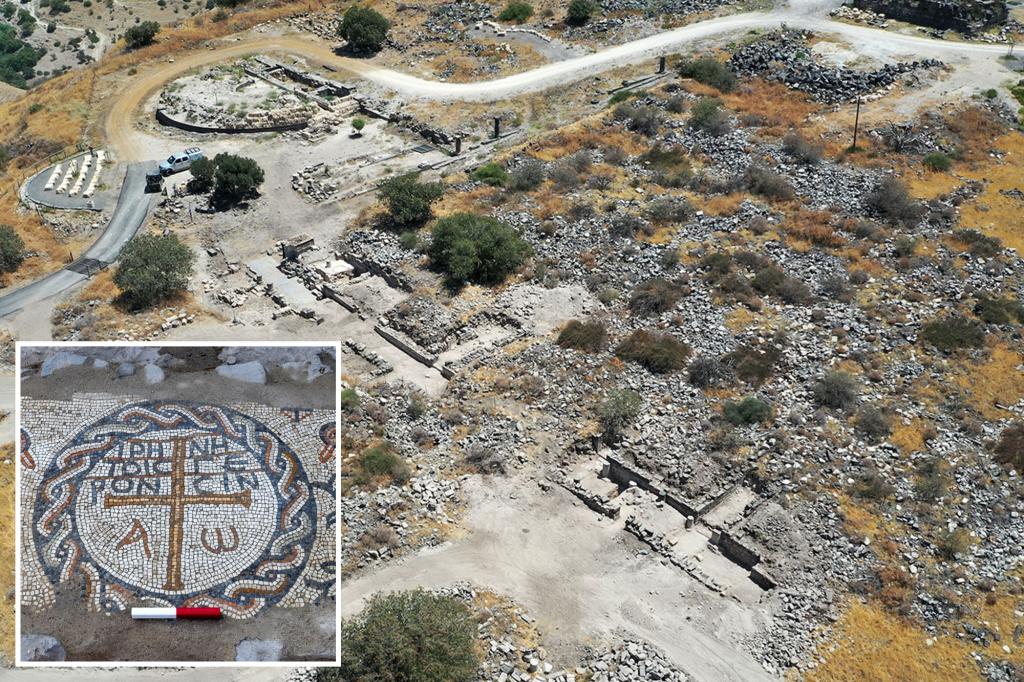

Archaeologists from the University of Haifa’s Zinman Institute of Archaeology have uncovered a 1,600‑year‑old building in the ruins of the ancient city of Hippos that they say was a Christian care facility for the elderly. A mosaic at the building’s entrance bears a Koine Greek inscription translating to “Peace be with the elders,” a message researchers say intentionally designated the structure’s purpose.

The building, located about 320 feet from Hippos’ central plaza and within a residential block, dates to the fourth or fifth century A.D., according to the team. Excavators were struck by the floor design at the entrance and by iconography incorporated into the mosaic—cypress trees, fruit and Egyptian geese—which researchers interpret as symbols of everlasting life, abundance and blessed souls.

The University of Haifa announced the discovery Aug. 18 and the research team published its findings in the Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy. In statements reported by Israel’s TPS‑IL news agency, lead investigators described the find as possible material evidence for organized elderly care in Byzantine society. "It shows that Byzantine society established not only religious centers but also places dedicated to dignity and care for its seniors," said Michael Eisenberg, Ph.D., of the Zinman Institute.

Textual sources from the fifth and sixth centuries have previously recorded the existence of institutions for older people, but physical evidence has been sparse. The researchers called the Hippos mosaic "a tangible, dated, and clear indication of an institution designed for the elderly," and said it may provide one of the earliest material testimonies in the Holy Land showing Christian communities taking on responsibilities once managed within family networks.

Archaeologists emphasize the communal and spiritual character of the facility. The building’s proximity to the city center and its formal entrance mosaic suggest it was integrated into urban life rather than being an isolated household space. The placement of the inscription at the doorway, the team said, was likely intended to communicate the building’s purpose directly to residents and visitors.

The decorative program of the mosaic aligns with known symbolic vocabularies from the period. Cypress trees were commonly associated with notions of everlasting life; fruits frequently signified abundance and eternal life; and Egyptian geese appeared in late antique iconography as markers of blessed souls. Researchers interpret the combination of text and imagery as an explicit, public statement about the building’s role.

Scholars noted that while references to care for the elderly appear in late antique literature, archaeological corroboration has been limited. The Hippos discovery therefore offers a rare glimpse into how social values and communal responsibilities were enacted in a Byzantine urban setting. The research team said the find illuminates daily life for older people in antiquity and reflects a broader shift in which Christian institutions assumed social functions beyond strictly religious duties.

The excavations at Hippos are part of ongoing archaeological work at the site near the Sea of Galilee, long known as a bishop’s seat during the Byzantine era. The team’s report underscores the potential for urban archaeological remains to alter understandings of social organization in late antiquity. Further study of the site, including publication of detailed architectural and epigraphic analyses, will be necessary to clarify the building’s full program and to compare it with other civic and communal institutions from the period.

The University of Haifa team framed the discovery as evidence that practices of organized elder care were present in late antique society, saying the mosaic "is living proof that care and concern for the elderly are not just a modern idea, but were part of social institutions and concepts as far back as about 1,600 years ago." The find adds a material dimension to textual references and may reshape discussions about the origins and spread of communal care practices in the Byzantine world.