Archaeologists Unearth 2,800-Year-Old Dam Near Jerusalem’s Pool of Siloam

Massive First Temple–period structure, dated to 805–795 B.C., suggests large-scale water engineering in response to drought and flash floods

Archaeologists have uncovered a massive stone dam in Jerusalem’s City of David, a short distance from the Pool of Siloam, officials said, in a find that sheds new light on water management in the First Temple period.

The structure, discovered during excavations within the Jerusalem Walls National Park, has been dated to between 805 and 795 B.C., a span of about 10 years, making it the oldest dam found in Jerusalem and the largest known in Israel from antiquity. The joint study by the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Weizmann Institute of Science was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Aug. 25, and the Antiquities Authority released further details on Aug. 30.

The stone-built dam measures roughly 39 feet (12 meters) high, 69 feet (21 meters) long and about 26 feet (8 meters) wide. Researchers determined its age through radiocarbon analysis of twigs and branches incorporated in the dam’s mortar, yielding an unusually narrow margin for an ancient structure.

Excavation directors said the dam was designed to collect water from the Gihon Spring and to capture episodic floodwaters flowing down the main valley of ancient Jerusalem. The team wrote that the engineering likely responded to a period of prolonged low rainfall punctuated by short, intense storms that could cause flash flooding.

"All the data pointed to a period of low rainfall in the Land of Israel, interspersed with short and intense storms that could cause flooding," the excavation directors said in a statement. "It follows that the establishment of such large-scale water systems was a direct response to climate change and arid conditions."

IAA Director Eli Escusido called the find "one of the most impressive and significant First Temple-period remains in Jerusalem" and said the discovery underlines the city's complex archaeological record. "In recent years, Jerusalem has been revealed more than ever before, with all its periods, layers and cultures — and many surprises still await us," he said.

The dam lies near the Pool of Siloam, a water basin fed by the Gihon Spring that was rediscovered in 2004 and is known in Christian tradition as the site where, according to the Gospel of John, Jesus told a man blinded from birth to wash and regain his sight. The Gospel recounts that the healed man "went and washed, and then I could see," a passage often cited in descriptions of the pool's historical and religious significance.

The newly reported dam adds to a growing body of evidence that inhabitants of ancient Jerusalem engaged in large-scale hydraulic works to secure water supplies and protect the city from floods. The research team suggested the structure could have been built under the reign of either King Joash or King Amaziah, rulers associated with the 9th century B.C., but they stopped short of asserting a definitive royal patronage.

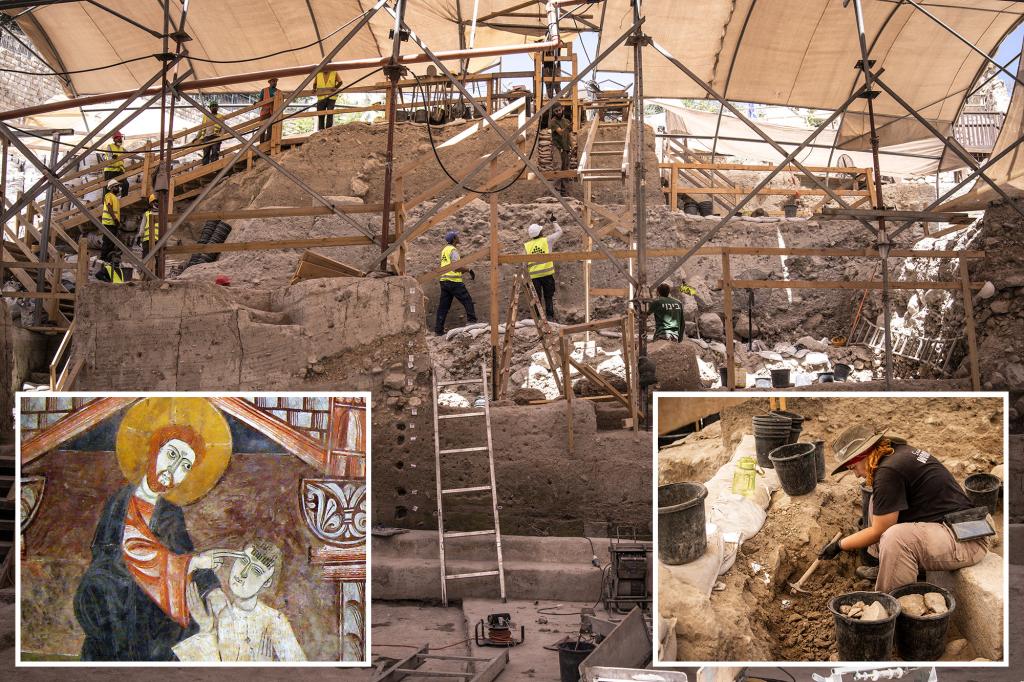

Archaeological photographs released with the study show laborers and researchers working around the massive stone structure, which required coordinated construction and planning. The team emphasized that the dam’s size and sophisticated design point to organized communal or state-level efforts to manage scarce water resources in a marginal climate.

The discovery comes amid several recent finds in Jerusalem that illuminate different periods of the city's long history. Earlier this year, researchers reported evidence of an ancient garden at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the recovery of a coin minted shortly before the destruction of the Second Temple.

The authors of the PNAS paper and the Antiquities Authority said further study of the dam and surrounding deposits could clarify how water systems were integrated into the urban fabric of ancient Jerusalem and how inhabitants adapted to environmental stressors. Publication of the research makes the detailed data available to other scholars and opens avenues for comparative study of ancient hydraulic engineering in the region.