Artemis II looms as NASA presses ahead with lunar tests amid renewed moon-landing skepticism

NASA outlines the crewed, 10-day Artemis II mission around the Moon, while online debates about space and the Moon landings intensify on social media.

NASA is moving forward with Artemis II, a crewed lunar test flight planned for February 2026 that will carry four astronauts on a 10-day voyage around the Moon. The mission aims to validate the performance of the Orion spacecraft and the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket under flight conditions expected in the lead-up to a future crewed lunar landing. Although Artemis II will not land on the Moon, NASA officials say the mission is a critical step in verifying life-support, navigation, communications, and spacecraft systems before any crewed surface mission.

The crew for Artemis II consists of four astronauts: Christina Koch, Victor Glover, Reid Wiseman, and Jeremy Hansen. They will pilot Orion on a path that will loop around the Moon and return to Earth, marking the first crewed lunar trajectory in more than half a century. The mission underscores NASA’s emphasis on testing the spacecraft and its operations rather than achieving a lunar touchdown during this flight. As NASA outlined the plan, observers noted that Artemis III is still targeted to include a lunar landing, with mid-2027 as the current window for a first surface landing.

Over the course of roughly 10 days, the crew will travel about 5,700 miles (9,200 kilometers) beyond the Moon, pushing the spacecraft’s life-support systems to their limits and gathering data on how human bodies react to extended deep-space exposure. The mission will set the record for the furthest point from Earth ever travelled by a human, a milestone in preparation for future lunar operations. The goal of Artemis II is to demonstrate operational readiness for the Artemis program’s next phase, including the crewed landing envisioned under Artemis III, which NASA has tied to mid-2027 as a target.

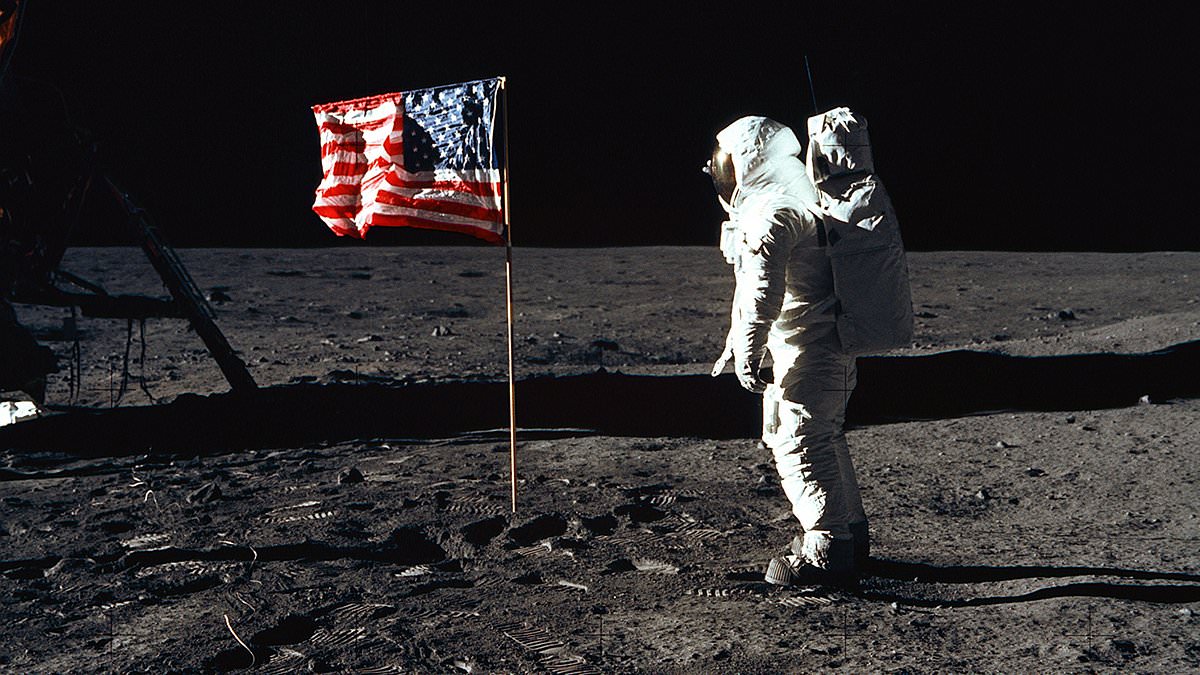

The renewed focus on Artemis II has coincided with a surge of online discussion and, in many cases, conspiracy theories about space exploration. On social media platforms, some commenters questioned why a mission would loop around the Moon without a landing, arguing that it implies NASA never went to the Moon at all. One post captured the sentiment by suggesting that modern missions are a test of funding and infrastructure rather than a genuine lunar return, while others mocked the idea with quips about CGI and stagecraft. A recurring refrain across threads is the claim that lunar achievements of the past were faked or fabricated, a notion that has persisted in various forms for decades.

Among the more pointed online reactions, a number of posters dismissed Artemis II as evidence that the Moon landings were never real. One user wrote, “I believe that the American missions of the 1950s are fake unless modern humans land on the Moon. It’s been over 70 years and we still can’t go to the Moon?” Another commented, “So NASA are going to the Moon again but they are not actually landing—what a load of fake BS.” Others used the moment to argue that space itself is an illusion, and that governments spend lavishly to maintain a cover story.

Public attitudes toward NASA conspiracies have been studied in recent years. A University of Miami survey reported that roughly 10 to 12 percent of Americans believed the Moon landings were faked, a share that had risen modestly since the early 2020s. Researchers noted that while interest in some conspiracy theories fluctuates, NASA-related theories have grown more prominent during periods of mission-focused publicity. Proponents of these theories often point to perceived inconsistencies or gaps in historical accounts, even as independent analyses and physical evidence have repeatedly corroborated the lunar landings.

Experts emphasize that the strongest proof of the Moon landings comes from physical artifacts and contemporaneous observations. The Apollo program delivered a retroreflector array to the lunar surface, enabling Earth-based lasers to measure the Earth–Moon distance with high precision. The missions also returned about 382 kilograms (842 pounds) of lunar rocks, whose unique chemical signatures have been studied extensively by scientists worldwide. In addition, observers at facilities such as the Jodrell Bank Observatory in England captured data showing the moment the lunar lander touched down, including the pilot’s manual control inputs during the final approach. Critics who question shadows or flag behavior point to explanations grounded in physics: shadows on the Moon can diverge in uneven terrain and low gravity, and the flag’s apparent movement was the result of a lack of atmosphere and the flag’s supports rather than wind.

NASA’s official timeline places Artemis I as an uncrewed test flight conducted in 2022, followed by Artemis II’s crewed flyby in the mid-2020s. Artemis III, still framed as the first crewed lunar landing, remains targeted for mid-2027, with Artemis IV proposing the construction of a lunar space station by 2028. The agency has stressed that Artemis II is not a landing mission; rather, its purpose is to validate spacecraft operations, crew interfaces, and mission-planning in deep-space conditions before attempting a landing on the lunar surface.

As the Artemis program advances, public interest and skepticism appear to be intertwined with broader discussions about space exploration, science funding, and the role of government-backed programs in pushing technological boundaries. NASA officials say that the data gathered on Artemis II will inform future missions, including the systems that will eventually enable sustained human presence on the Moon and, potentially, future crewed expeditions to Mars. In a climate of intense online chatter, the agency has urged the public to focus on verifiable evidence and the incremental steps that precede any ambitious leap into deep space.

In summary, Artemis II represents a pivotal, real-world test for NASA’s lunar ambitions: a focused, non-landing mission designed to prove core systems ahead of a historic crewed lunar landing. While online discourse continues to feature skepticism and even calls for alternative explanations, scientists and mission engineers point to decades of corroborated data—from rock samples to laser ranging—that affirm the reality of human spaceflight and the ongoing pursuit of lunar exploration.

Sources

- Daily Mail - Latest News - Moon landing conspiracy theories are reignited online as NASA reveals details for the Artemis II mission - as one sceptic jokes 'I hope they have better CGI this time'

- Daily Mail - Science & Tech - Moon landing conspiracy theories are reignited online as NASA reveals details for the Artemis II mission - as one sceptic jokes 'I hope they have better CGI this time'