Astronomers find 'forbidden' pulsar Calvera fleeing supernova far above Milky Way disk

The discovery of a pulsar roughly 6,500 light‑years above the galactic plane challenges expectations about where massive stars can form and explode

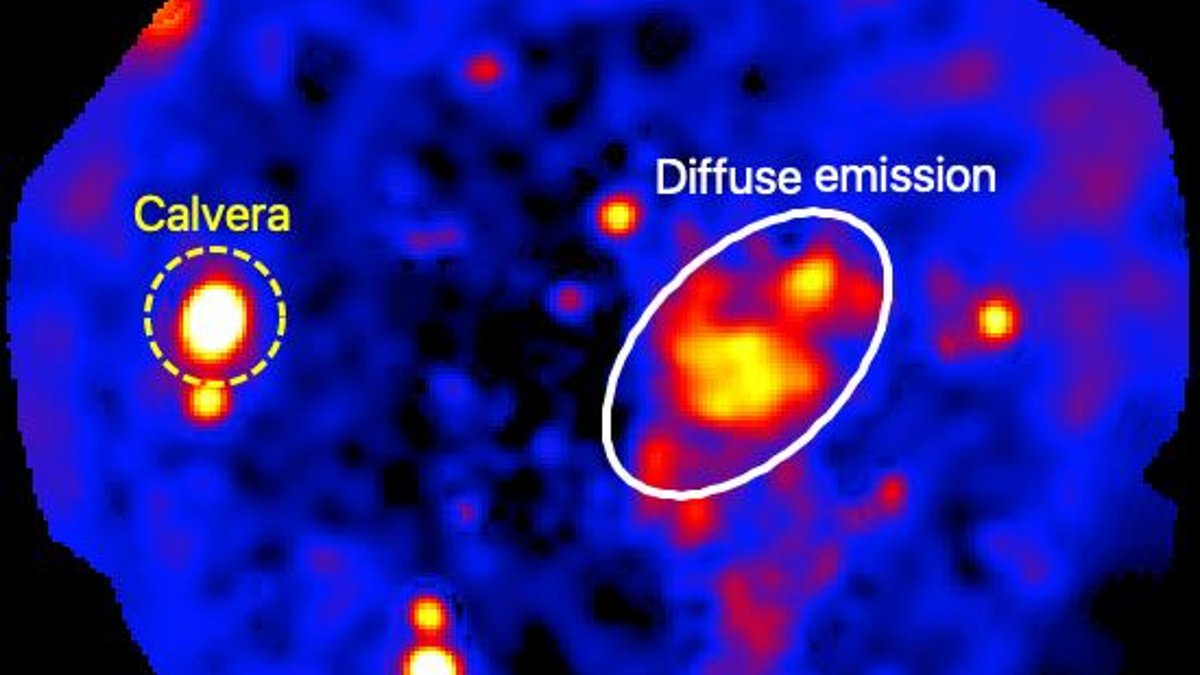

Astronomers have identified a runaway pulsar, known as Calvera, moving away from the site of a recent supernova roughly 6,500 light‑years above the plane of the Milky Way — a location where the progenitor star should not have been able to form. The finding, described by researchers from Italy's National Institute for Astrophysics, has been called “forbidden” because massive stars that end their lives as pulsars normally form in the dense gas and dust concentrated near the galactic disk.

Pulsars are rapidly rotating, ultra‑dense neutron stars left behind after massive stars collapse and explode as supernovae. Calvera was observed as a compact, high‑velocity object consistent with a neutron star escaping the aftermath of a massive stellar explosion at an unusually large distance from the Milky Way’s midplane. "Since a pulsar is the compact leftover of the explosion of a massive star, it is surprising to see it very far away from the galactic disk," said lead researcher Dr. Emanuele Greco of the National Institute for Astrophysics. "It means that during its normal life as a star, it ran away from the disk and then exploded."

The discovery raises questions about the origins and life histories of massive stars that produce neutron stars. Massive stars are expected to form and be retained in the thin disk of the galaxy, where molecular clouds and star‑forming regions are concentrated. Finding a neutron star originating from a massive progenitor at the observed height implies either an uncommon evolutionary path for the progenitor or a strong dynamical event that propelled the star far from its birthplace before it exploded.

One plausible explanation, noted by the team, is that the progenitor was a runaway star that left the disk during its main‑sequence lifetime and subsequently underwent core collapse in its elevated location. Runaway stars can be ejected from birth clusters by dynamical interactions with other stars or by the explosion of a binary companion; if such a star lived long enough, it could travel several kiloparsecs from its formation site before becoming a supernova. The current observations of Calvera are consistent with that scenario, according to the researchers.

The discovery also underscores the importance of mapping neutron star positions and motions to reconstruct the birth sites and evolutionary histories of massive stars. Precise measurements of Calvera’s velocity and trajectory, together with deeper observations of its surrounding environment, are needed to determine whether it was born in the disk and later migrated, or whether alternative explanations are required.

Calvera’s location and motion will likely prompt follow‑up observations across multiple wavelengths to constrain its age, speed and the characteristics of any faint supernova remnant. Such data can test models of stellar ejection, binary evolution and supernova kicks that can impart large velocities to newborn neutron stars. The system adds to a growing catalogue of neutron stars found in surprising environments and offers a nearby laboratory for studying how massive stars move and die in the galaxy.

The research was reported by the team led by Dr. Greco and colleagues at the National Institute for Astrophysics. Further peer‑reviewed publications and additional observational results are expected as astronomers pursue higher‑precision astrometry and multiwavelength follow‑up to clarify Calvera’s origins and implications for stellar population models.