Bacteria turn waste plastic into painkillers marks biotech breakthrough

Engineered E. coli converts a plastic-derived molecule into paracetamol, highlighting both the promise and limits of microbial manufacturing.

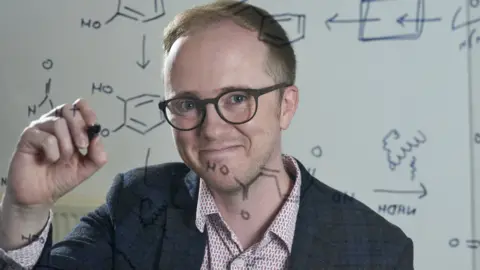

A genetically engineered strain of Escherichia coli has been used to convert a plastic-derived molecule into paracetamol, the common painkiller, in a development researchers describe as a potential milestone for turning waste into medicines. The work from the University of Edinburgh, led by chemical biotechnologist Stephen Wallace, demonstrates that a familiar laboratory microbe can be steered to produce a widely used drug from plastic-derived feedstocks.

E. coli remains the field’s main workhorse because of its fast growth, ease of handling and a long track record of genetic tools. It is a rod-shaped bacterium found in the guts of humans and animals, and non-pathogenic strains are routinely used in biotech labs. Wallace and colleagues have also shown that when given the right genetic tweaks the same microbe can transform waste plastic into other value-added products, such as the vanilla flavour and even perfume derived from fatberg waste. In industry, large vats of engineered E. coli churn out pharmaceuticals like insulin and a range of platform chemicals used to make fuels and solvents.

The broad success of E. coli as a model organism stems from its role in understanding basic biology. It grows quickly, is predictable in the lab and readily accepts foreign DNA. The organism was first identified in 1885 by Theodor Escherich, a German pediatrician studying infant gut microbes. In the 1940s scientists demonstrated that non-pathogenic strains could exchange genes, a discovery that advanced the concept of bacterial sex. The 1970s saw the first instance of genetic engineering using E. coli when foreign DNA was inserted, laying the groundwork for modern biotechnology. The 1978 production of synthetic human insulin in E. coli marked a turning point in medicine, and the organism’s complete genome sequence in the 1990s opened doors to deeper genetic manipulation.

Adam Feist, a professor at the University of California, San Diego who evolves microbes for industrial applications, emphasizes that E. coli’s practical appeal goes beyond theory. It grows rapidly, is robust across substrates, and tolerates a wide range of conditions. It freezes and revives well and hosts foreign DNA with relative ease, making it a dependable starting point for engineering new pathways. Cynthia Collins of Ginkgo Bioworks notes that while the portfolio of usable microbes has expanded, E. coli remains a cost-effective option in many manufacturing contexts, provided the product is not toxic to the cells or that tolerance can be engineered.

Yet some researchers worry that focusing on E. coli could limit innovation. Paul Jensen, a microbiologist at the University of Michigan, argues that many other microbes exist that could perform the same tasks more efficiently but are underexplored. He advocates bioprospecting in places such as landfills to discover organisms that already deal with plastics or other waste, suggesting that there may be bacteria better suited to certain jobs than E. coli. He points to mouth bacteria that show high acid tolerance and other microbes with surprising capabilities as examples of why breadth matters.

There are signs of fresh competition. Vibrio natriegens, a seawater-loving bacterium identified in the 1960s and revived in labs in recent years, has drawn attention for its ultra-fast growth rate—reported to be faster than E. coli—and its efficiency at taking up foreign DNA. Proponents say V. natriegens could speed up engineering programs aimed at big sustainability challenges, such as converting carbon dioxide and electricity into fuels or materializing microbes that mine metals. But the genetic tool kit needed for broad use is still being developed and the organism has yet to prove itself at industrial scale. In response, researchers have launched start-ups such as Forage Evolution to commercialize tools that make engineering this organism easier, though its practical use remains largely experimental.

Despite the challenges, the Edinburgh project demonstrates the potential of turning waste streams into medicines, a theme that sits at the intersection of science and industry. It also underscores the challenges of moving from laboratory demonstrations to scalable, real-world manufacturing, including safety, regulatory oversight and supply chain considerations. As the field advances, E. coli is likely to remain a central platform for foundational research even as other microbes emerge as possible co-stars in the biology of sustainability and drug production.