DNA genealogy helped solve Idaho murders in record time, researchers say

Forensic genetic genealogy linked to Bryan Kohberger in days after DNA on a knife sheath was tested, highlighting a method prosecutors say can accelerate solving cases

A DNA sample found on the clasp of a brown leather Ka-Bar knife sheath left at the Moscow, Idaho home where four University of Idaho students were killed in November 2022 was flown about 2,000 miles to a Texas laboratory for testing. The sample, recovered from the crime scene, did not match anyone in existing police databases when it arrived. Investigators then turned to forensic genetic genealogy, a process that uses a high-quality DNA profile built from crime-scene material to search distant family connections in public databases. Within 48 hours of starting analysis at Othram, the team had built a unique DNA profile and uploaded it to genetic genealogical databases, where matches quickly emerged and narrowed the field to a single suspect.

The timeline was all the more notable because the Thanksgiving period in 2022 had passed without an arrest and more than 19,000 tips had flooded in from the public. The DNA profile built from the knife-sheath sample proved unusually detailed, with hundreds of thousands of markers that allowed investigators to trace ancestry and homed in on a specific family with deep roots in the United States. From there, investigators cross-referenced the family’s location and heritage with other scannable clues from the case to limit the pool to a small number of drivers and vehicles associated with the suspect.

Security footage near the victims’ home showed a white Hyundai Elantra with Pennsylvania plates circling the residence around the time of the murders, then speeding away moments later. Investigators focused on the Elantra’s owner in Idaho and found a critical clue: the driver had changed his license plates from Pennsylvania to Washington only days after the killings, a detail that helped refine the suspect pool. A surviving roommate had given a description that included bushy eyebrows consistent with the man later identified by the genetic genealogy work.

With the prime suspect narrowed to a single family and then to a specific individual within that lineage, investigators traced Kohberger to his parents’ home in the Poconos for a trash pull conducted under disguise. A Q-tip found in the garbage contained DNA that matched the person whose DNA had been found on the knife sheath, providing a pivotal corroboration of the genetic profile. Late on December 29, 2022, Moscow police officers informed Stacy Chapin, mother of one of the victims’ friends, that they had identified the man who killed her son, Ethan Chapin. The lab’s analysis had begun yielding results within hours of starting and, after a brief verification process, Kohberger’s name was the focus of the investigation for the first time.

The rapid identification marked a turning point in the case. Kohberger was later tracked to his graduate studies and arrests followed. The pattern of evidence also allowed investigators to contextualize other pieces of the case, such as the murder weapon and additional traces found at the scene. Kohberger was ultimately charged with the murders of Ethan Chapin, Xana Kernodle, Madison Mogen and Kaylee Goncalves and later pleaded guilty in July 2024, receiving a life sentence without the possibility of parole.

Mittelman and other Othram scientists emphasized that forensic genetic genealogy is most powerful when the evidence from a crime scene is of high quality and can be translated into a genome-wide profile. They note that DNA can be transferred in various ways, but the method’s value lies in identifying probative DNA—the DNA that directly ties a person to the crime scene rather than incidental contact. In this case, the DNA found on the murder weapon and its connection to a suspect through distant relatives provided a robust link that supported the authorities’ case. The defense, which challenged certain aspects of the genetic genealogy evidence, faced a range of legal arguments about the technique’s admissibility, but Ada County Judge Steven Hippler ultimately allowed the evidence to stand and Kohberger’s defense did not prevail in those challenges.

The case has been cited by supporters of expanding access to forensic genealogy. Othram’s method, which relies on sequencing a large panel of genetic markers and then querying genealogical databases, has helped solve other cold cases, including cases involving missing or unidentified victims. Advocates say broader adoption could help families obtain answers more quickly, but funding remains uneven—federal support for this work is limited, and many law enforcement agencies must rely on local budgets.

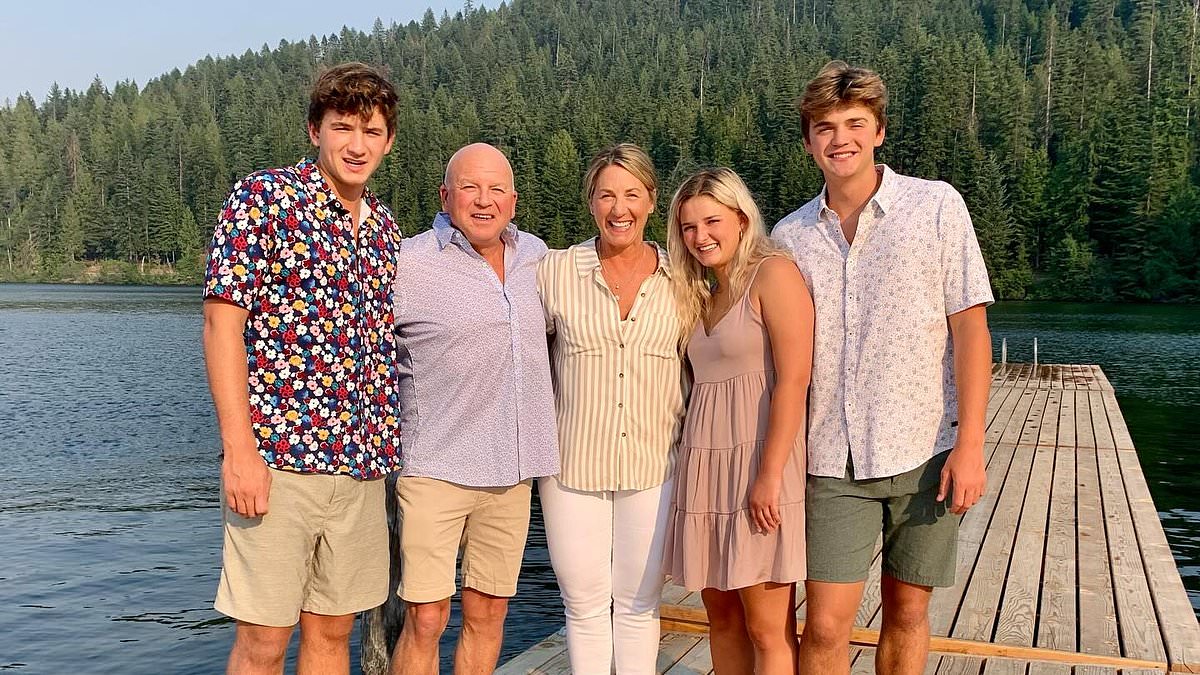

For the Chapin family, the ability to learn who killed Ethan—and to see that suspect brought to justice—has brought a measure of closure after years of uncertainty. They have since become advocates for expanding access to this technology, saying it could spare other families the long and painful search that followed their son’s death. As they note, Thanksgiving 2022 was the hardest holiday they endured; in 2024, with the case resolved, they describe a fundamentally different sense of gratitude, rooted in the work of scientists who pursued the truth in real time. In the broader landscape of criminal investigations, supporters say the Idaho quadruple murder demonstrates how rapidly evolving genetic science can intersect with traditional investigative work to solve even the most devastating crimes.