Gut bacterial molecule drives liver sugar and fat production; biodegradable ‘trap’ reduces damage in mice

Study in Cell Metabolism identifies D‑lactate from gut microbes as a trigger for metabolic dysfunction‑associated steatotic liver disease and reports improved glucose control and reduced liver fibrosis in mice given an oral substrate trap.

Canadian researchers report that a molecule produced by gut bacteria can push the liver to make excess sugar and fat, a finding they say helps explain rising rates of fatty liver disease and offers a potential new therapeutic approach.

In experiments reported in the journal Cell Metabolism, investigators identified the microbial metabolite D‑lactate as a driver of increased blood glucose and liver fat. The team designed a biodegradable "gut substrate trap" intended to bind D‑lactate in the intestine and prevent its absorption; mice fed the trap showed lower blood glucose, improved insulin resistance and reduced liver inflammation and fibrosis compared with control animals, despite no change in diet or body weight.

"This is a completely new way to think about treating metabolic diseases like fatty liver disease," said study lead author Jonathan Schetzer, a professor of biomedical sciences at McMaster University. "Instead of targeting hormones or the liver directly, we're intercepting a microbial fuel source before it can do harm."

The work builds on the nearly century‑old Cori cycle, described by Carl and Gerty Cori in 1974, in which L‑lactate produced by muscle is transported to the liver and converted to glucose to fuel muscle activity. The Canadian team focused on the lesser‑studied D‑lactate, showing that obese individuals have higher circulating levels of the molecule and that much of it is produced by gut microbes. In experimental comparisons, D‑lactate raised blood sugar and liver fat more dramatically than L‑lactate.

To test whether blocking intestinal uptake of D‑lactate could blunt its metabolic effects, researchers created the gut substrate trap and administered it orally to mice on a high‑fat diet. Treated animals exhibited improved markers of glucose metabolism and fewer signs of liver injury, including lower markers of inflammation and reduced fibrosis — the accumulation of fibrous connective tissue that occurs in response to chronic liver damage.

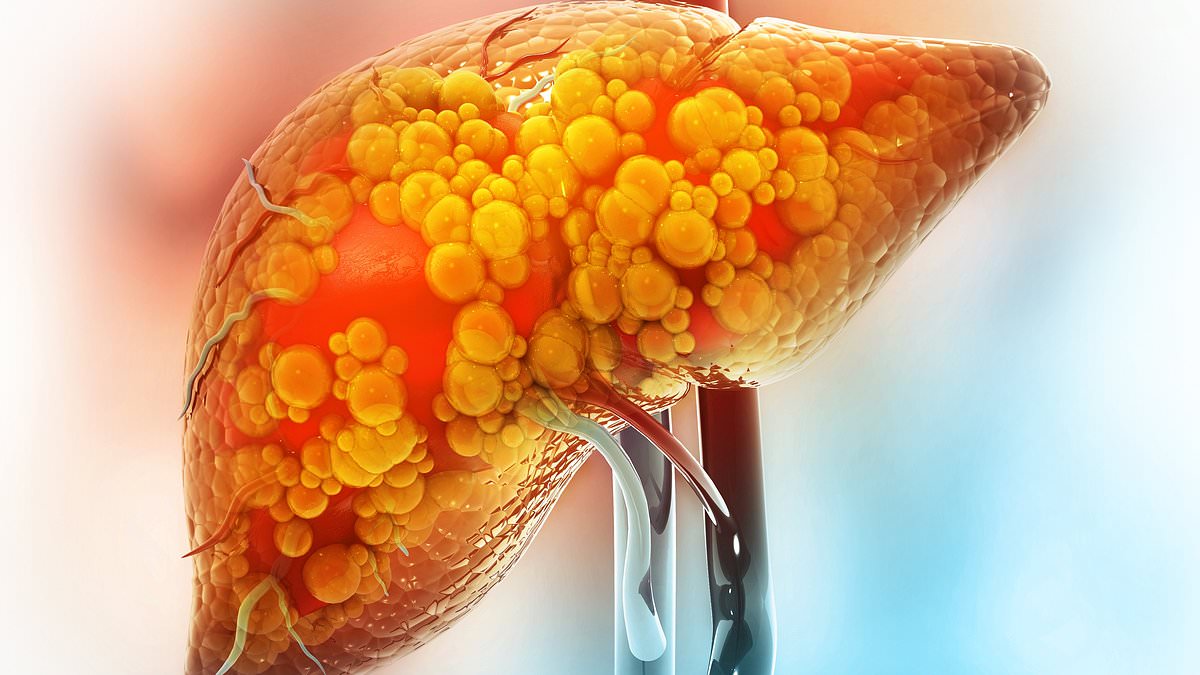

Metabolic dysfunction‑associated steatotic liver disease, formerly known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, is caused by a build‑up of fat in the liver that can lead to inflammation and scarring. Clinicians say the condition is increasingly common as rates of overweight and obesity rise. The British Liver Trust has reported that liver disease is the only major disease with continually rising death rates and that mortality has increased roughly fourfold over the past five decades. The organization recorded about 11,000 deaths from liver disease last year.

"People who develop MASLD are often overweight or have diabetes," said Philip Newsome, director of the Roger Williams Institute of Liver Studies at King's College London. "We're seeing an increase in liver disease in the U.K., and the challenge is that symptoms are often unnoticeable until it's too late." Newsome added that it is a "common and dangerous misconception" that alcohol is the only cause of liver scarring, noting that excess fat and uncontrolled blood sugar can produce the same outcome.

Public health data underline the scale of the problem: recent figures indicate nearly two‑thirds of adults in England are overweight, and about 26.5 percent — roughly 14 million people — are classified as obese. Policymakers and clinicians have moved to expand treatment options for obesity, including allowing general practitioners to prescribe glucagon‑like peptide‑1 receptor agonists, known as GLP‑1s, and tens of thousands of patients are receiving such therapies through the National Health Service and private clinics.

The authors of the Cell Metabolism study say their findings point to a new class of interventions that act in the gut to reduce a microbial contribution to metabolic disease. The experiments reported were conducted in mice, and the researchers note that further work is needed to test safety and effectiveness in humans and to define which patients might benefit most.

If subsequent studies confirm similar effects in people, gut‑targeted approaches such as substrate traps could complement existing lifestyle and pharmacologic strategies for preventing progression of fatty liver disease, particularly in high‑risk obese and diabetic populations. For now, clinicians emphasize early detection and management of metabolic risk factors, including weight control, blood‑pressure management and glucose regulation, to reduce the likelihood of progression to cirrhosis or liver cancer.