James Webb finds candidate primordial black hole from the universe's infancy

A 50-million-solar-mass, 'nearly naked' object observed 600–700 million years after the Big Bang raises questions about early black hole formation

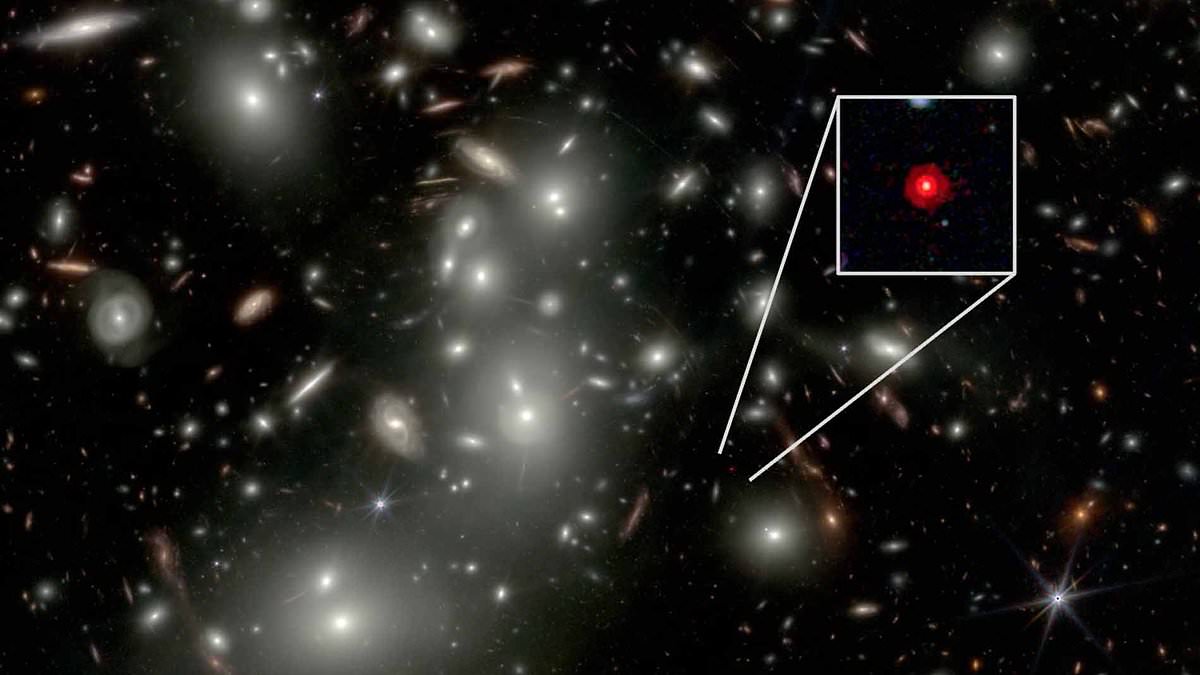

Researchers using the James Webb Space Telescope have identified an unusually massive and sparsely surrounded black hole at the edge of the observable universe that may have formed in the first moments after the Big Bang.

The object, seen at an epoch roughly 600 to 700 million years after the Big Bang, appears to contain about 50 million times the mass of the Sun. That combination of extreme mass and very early cosmic age led investigators to describe it as a candidate "primordial black hole," an entity that would have formed directly from conditions in the infant universe rather than from the collapse of a dying star.

The object has been called "nearly naked" by the team because it lacks the bright, extended host galaxy that typically surrounds supermassive black holes. Traditional models hold that massive black holes grow over time by accreting gas and merging with other black holes inside galaxies. Finding a 50-million-solar-mass object so early challenges those growth scenarios, which struggle to assemble such mass in only a few hundred million years.

Standard black hole formation occurs when massive stars exhaust their nuclear fuel and collapse, a process that requires multiple generations of stars and substantial time to build up the supermassive objects seen in the nearby universe. By contrast, primordial black holes are a theoretical class of objects that could have formed directly from extreme density fluctuations in the first fractions of a second after the Big Bang, before the first stars and galaxies existed.

"In this scenario, black holes would be the first entities formed in the universe, well before the formation of the first stars and first galaxies," said co-author Professor Roberto Maiolino of the University of Cambridge in comments to the Daily Mail. Researchers caution that the primordial interpretation remains a hypothesis that requires additional evidence.

The discovery relied on Webb's infrared sensitivity to detect faint, redshifted light from the early universe. The telescope has already revealed a number of unexpectedly massive or luminous objects at high redshift, reigniting debate among cosmologists and astronomers about how quickly structure could grow after the Big Bang.

Several alternative explanations remain under consideration. One is that the object is a rapidly growing black hole that gained mass through unusually efficient accretion or multiple early mergers, possibly aided by a dense local environment. Another is that the observation could be of a black hole whose host galaxy is unusually faint or has been disrupted, making the surrounding starlight difficult to detect with current data.

Confirming a primordial origin would have profound implications for cosmology and fundamental physics. Primordial black holes have been proposed in some theoretical frameworks as contributors to dark matter or as probes of conditions in the very early universe. A confirmed detection would require revisions to models of early-universe particle physics, the statistics of primordial density fluctuations, and scenarios for cosmic structure formation.

Researchers emphasize that more data are needed to test competing interpretations. Planned follow-up observations with Webb and other facilities will aim to measure the object's spectrum, to search for faint host starlight or signs of a surrounding galaxy, and to better constrain its redshift and environment. Additional theoretical work will also be required to determine whether known astrophysical growth mechanisms could produce such a mass so early.

The identification of this candidate adds to a growing set of surprising early-universe findings from Webb, underscoring both the telescope's capability to probe cosmic dawn and the remaining uncertainties about how the first black holes and galaxies emerged. If the primordial hypothesis is borne out by future observations, it would reshape understanding of the universe's first moments and the physical processes that followed.