Leopard‑spot rocks on Mars yield strongest evidence yet of potential past life, study says

Perseverance found 3.5‑billion‑year‑old mudstones dotted with mineral 'spots' that meet NASA criteria for potential biosignatures; confirming biological origin would require a sample return.

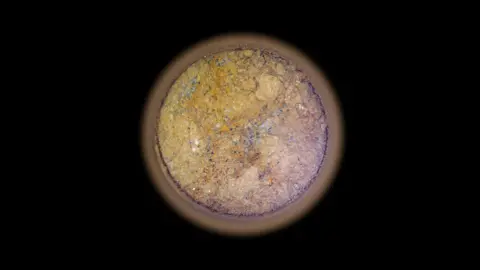

Unusual "leopard‑spot" and "poppy seed" markings discovered on Mars by NASA's Perseverance rover contain minerals that scientists say are the most compelling potential biosignatures identified on the planet to date.

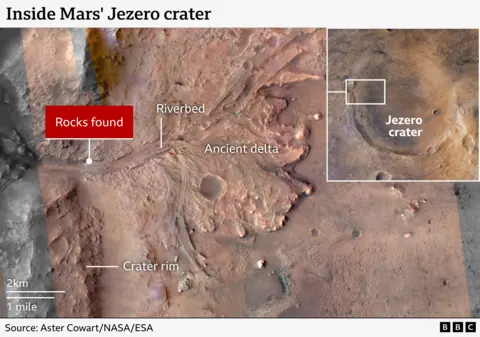

The features were found in fine‑grained mudstones at the base of a river‑carved canyon within the Bright Angel Formation in Jezero Crater. The rocks, about 3.5 billion years old, were formed from clays deposited in the lake that once occupied the crater, and the rover's onboard instruments detected mineral assemblages that suggest chemical reactions between the mud and organic matter.

The findings, reported in the journal Nature by a team led by Joel Hurowitz of Stony Brook University, stop short of a claim that life existed on Mars but meet NASA's definition of a "potential biosignature"—features that warrant further investigation because they could have formed by biological processes. The study authors and other mission scientists say the materials are worth returning to Earth for laboratory analysis that could confirm or refute a biological origin.

"We've not had something like this before," said Sanjeev Gupta, a planetary scientist at Imperial College London and a co‑author of the paper. "We have found features in the rocks that if you saw them on Earth could be explained by biology — by microbial process. So we're not saying that we found life, but we're saying that it really gives us something to chase."

Perseverance, which landed inside Jezero Crater in February 2021, examined the rocks using its suite of instruments that include cameras, spectrometers and an onboard sample‑handling system. Those data were transmitted to Earth for detailed study. The team interprets the spotted patterns as concentrations of newly formed minerals created when organic matter and the lake mud reacted; on Earth, analogous mineralization commonly results from microbially mediated chemistry.

"We think what we've found is evidence for a set of chemical reactions that took place in the mud that was deposited at the bottom of a lake — and those chemical reactions seem to have taken place between the mud itself and organic matter — and those two ingredients reacted to form new minerals," Hurowitz said.

The paper evaluates alternative, non‑biological pathways for producing the mineral patterns. The authors found that abiotic scenarios could explain the observations only under conditions that would have required high temperatures or other heat‑driven processes that are not supported by the appearance and context of the rocks. While the non‑biological routes could not be completely ruled out, the investigators say they face inconsistencies with the field evidence returned by Perseverance.

Perseverance has already collected samples from the Bright Angel Formation and stored them in sealed metal canisters. Those caches were placed on the Martian surface to await a future sample‑return campaign that would transport the material to Earth for comprehensive laboratory tests that are impossible with rover equipment alone. Many scientists say such analyses are the only definitive way to determine whether the mineral features preserve signs of ancient microbial activity.

The prospect of bringing these samples home is, however, uncertain. A joint NASA‑European Space Agency (ESA) architecture for a Mars sample return has been under development for several years. Recent budget proposals from the U.S. administration have placed severe cuts to NASA's science budget, and officials have identified the sample‑return effort as one of the programs at risk. Separately, China's space agency has announced plans for its own Mars sample‑return mission that could launch in the late 2020s.

"We need to see these samples back on Earth," Gupta said. "I think for true confidence, most scientists would want to see and examine these rocks on Earth — this is one of our high‑priority samples to return."

The discovery adds to a growing body of evidence that early Mars hosted environments capable of sustaining complex aqueous chemistry. Geological and orbital data have long indicated that Jezero Crater once contained a lake fed by an inflowing river; fine sediments and clay minerals in the Bright Angel Formation corroborate a long‑lived, sedimentary setting that is favourable for preserving organic matter and biosignatures.

Mission scientists emphasize caution. The Nature paper presents detailed mineralogical and chemical analyses and discusses both biological and abiotic formation paths. Authors draw attention to the need for more exhaustive laboratory measurements on returned samples to test isotopic signatures, organic molecular complexity and microstructural relationships that can distinguish life‑related processes from purely chemical ones.

Perseverance will continue its exploration of Jezero and its sampled caches remain a potential bridge to definitive answers. Until those samples can be examined in terrestrial laboratories, the leopard‑spot mudstones will remain among the most tantalising, but not conclusive, evidence that life may once have existed on Mars.