New study questions Titan’s buried ocean, suggesting ice, slush and pockets of water instead

Researchers reexamine Cassini data and propose Titan’s interior may lack a global ocean, though pockets of liquid water could exist within slushy layers.

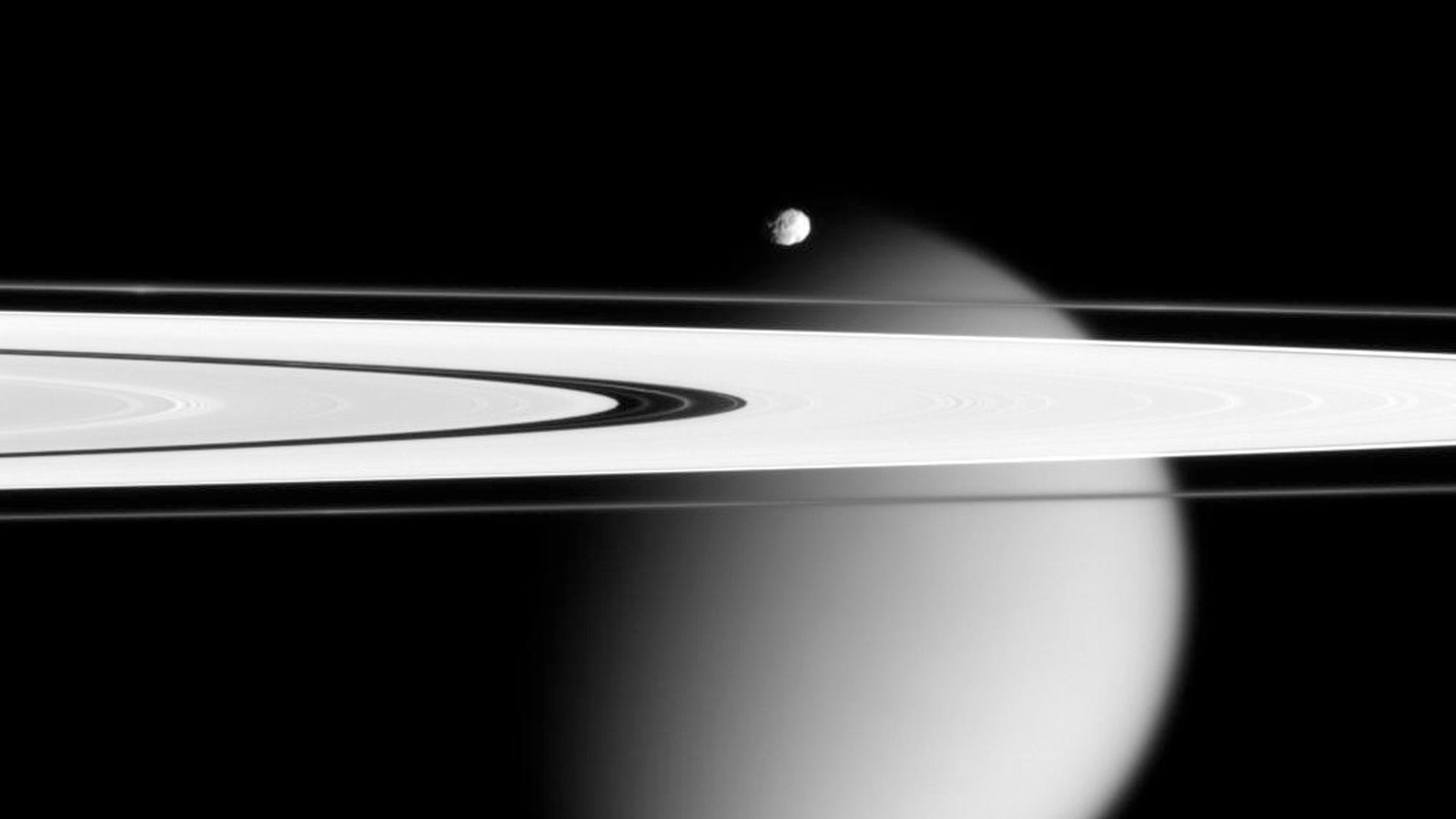

Saturn’s moon Titan may not have a vast underground ocean after all, a new study suggests. Instead, Titan could host deep layers of ice and slush with pockets of melted water that might, in theory, support microbial life. The analysis, published in Nature, reexamines observations from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft and challenges the decade‑long assumption of a buried global ocean beneath Titan’s crust. While Titan’s surface hosts lakes of liquid methane, no signs of life have been detected there or on Titan to date.

Led by Flavio Petricca of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the research team applied improved data processing to measurements of Titan’s response to Saturn’s gravity. If Titan had an ocean beneath its crust, the surface would respond almost immediately to tidal forces; the researchers detected a roughly 15‑hour lag, a finding that aligns with a thick, slushy interior rather than a uniform underground ocean. Computer models indicate Titan’s interior may be layered, with an outer ice shell about 100 miles (170 kilometers) thick, beneath which lie strata of ice, slush, and pockets of liquid water extending more than 340 miles (550 kilometers) deep. The warmer water pockets could reach temperatures near 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius), raising the plausibility of habitable niches within Titan’s interior.

The findings add a new layer of complexity to Titan’s interior, complicating earlier projections of a global ocean riding beneath an icy crust. Proponents of a buried ocean had argued that Titan’s gravity and orbital dynamics supported a sizable global reservoir of liquid water; the new interpretation relies on refined processing of Cassini’s gravity data and an updated understanding of how Titan’s interior responds to Saturn’s tides. Baptiste Journaux of the University of Washington, a co‑author on the study, stressed that the possibility for life remains an open question. “There is strong justification for continued optimism regarding the potential for extraterrestrial life,” he wrote in an email, noting that even if life were limited to microscopic forms, Titan could still host it within temperate pockets of liquid water shielded by ice.

Luciano Iess of Sapienza University of Rome, whose earlier work with Cassini data pointed to a hidden ocean, remained cautious. “Certainly intriguing and will stimulate renewed discussion ... at present, the available evidence looks certainly not sufficient to exclude Titan from the family of ocean worlds,” Iess said via email. The evolving view underscores how Cassini’s legacy continues to shape hypotheses about Titan, even as new analyses offer alternative explanations for the moon’s interior structure.

NASA’s Dragonfly mission, a rotorcraft‑style lander planned to reach Titan later this decade, could provide critical constraints on Titan’s interior by examining its surface chemistry, atmosphere and potential subsurface processes. Journaux is part of the Dragonfly science team, and the mission aims to illuminate how Titan’s chemistry evolved and whether habitable environments may persist there today.

Titan’s size makes it a major waypoint in the solar system’s inventory of potential watery worlds. At about 3,200 miles (5,150 kilometers) across, Titan is the second‑largest moon in the solar system, after Ganymede, and it already reveals a world of methane lakes on a frigid surface. Its interior, shaped by Saturn’s strong gravity, is an ongoing source of scientific debate about how such bodies store energy, produce heat and potentially harbor life.

The Cassini‑Huygens mission, launched in 1997, delivered a flood of data about Titan and Saturn’s system before ending with a controlled plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere in 2017. The data set remains a touchstone for contemporary investigations into Titan’s interior, not least because it provides the long temporal baseline needed to study Titan’s gravity and rotation. In the broader view, Titan sits alongside other suspected water worlds such as Saturn’s Enceladus and Jupiter’s Europa, where geysers or plumes indicate subsurface activity, though Titan’s surface and interior conditions appear distinct.

If Titan’s interior is indeed a labyrinth of ice, slush and pockets of liquid water, the implications extend beyond academic debate. The prospect of habitable niches within icy worlds continues to motivate missions and instruments designed to detect chemical energy sources and microbial potential. Scientists emphasize that any life, if present, would most likely be microscopic and adapted to extreme environments, underscoring the need for targeted measurements and in‑situ analyses.

Titan’s evolving story illustrates the iterative nature of planetary science: new data processing methods, refined models and fresh perspectives can reshape long‑standing theories about how the solar system’s worlds are built—and what they might still hide beneath their surfaces.