Replaceable You: Regenerative medicine advances toward bio-printed organs and personal pig implants

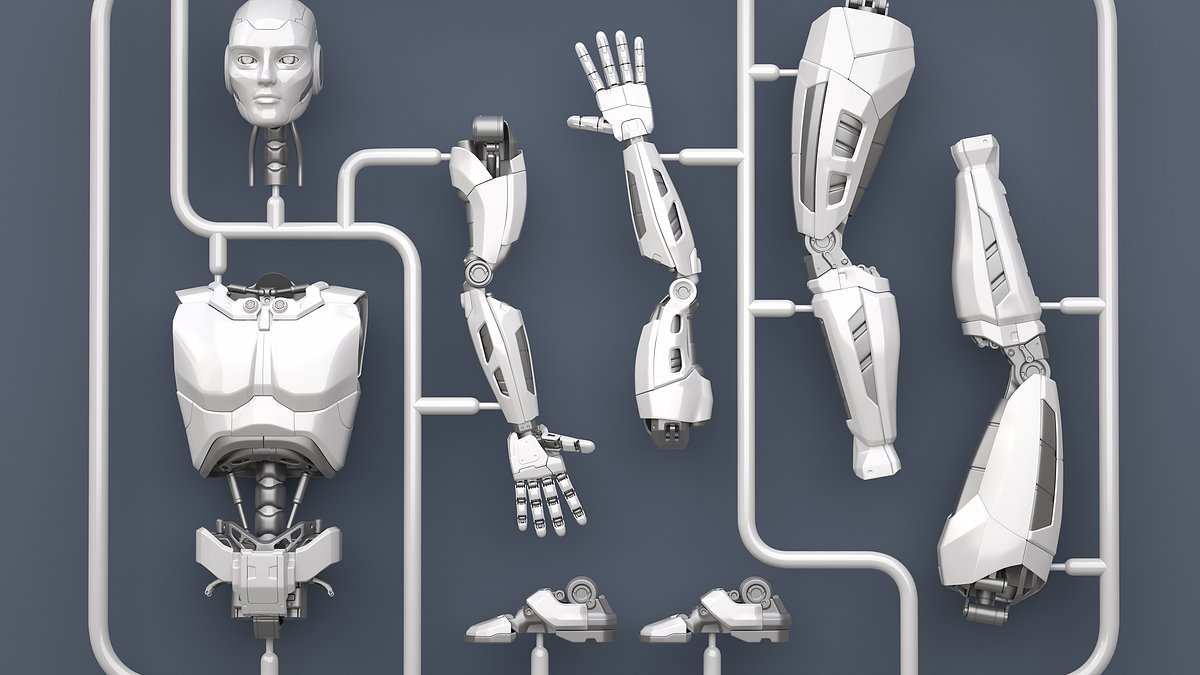

Researchers outline a future in which organs and body parts could be grown, swapped, or enhanced with gene editing, bioprinting, and advanced prosthetics.

Regenerative medicine is edging toward a future in which large parts of the human body could be replaceable. Researchers are pursuing xenotransplantation, bioprinting, and stem-cell therapies that could ultimately yield organs and tissues grown from a patient’s own cells or from gene-edited animal hosts. Experts say the pace of discovery has accelerated to the point where the line between science fiction and medicine is increasingly blurred, with predictions that fully replaceable body parts may be within reach in a decade or so. The conversation spans everything from pig organs to finger-derived penile reconstruction, and from high-tech prosthetics to 3D bioprinted tissues that could one day function like native organs. The discussions appear in the context of a broader shift toward personalized, lab-grown biology that could redefine what it means to be replaceable.

Personal pigs for parts are no longer confined to the lab’s edge cases. In xenotransplantation, scientists are working toward pigs whose genes have been edited to resemble human biology closely enough that their organs could be grown to meet a patient’s needs. In practice, the goal is a pig embryo in which specific pig genes are deactivated, creating a developmental window into which a patient's human pluripotent stem cells could be introduced. The hope is that the human cells would grow into a human organ inside the pig, while the pig’s immune environment would reduce rejection since the organ would be seen, in part, as part of the pig’s biology from which it originated. This concept—often described as a “personal pig”—is described by researchers as chimerism, using the pig to grow human organs while trying to avoid immune mismatch once transplanted. The approach relies on precise gene-editing techniques, notably CRISPR, to knock out target pig genes and create space for human tissue.

The practical steps, as outlined by researchers in Chengdu, involve starting with a pig blastocyst, editing out certain genes so the pig cannot form a kidney or other organ, and then introducing human pluripotent stem cells. Those cells would ideally derive an organ that carries the patient’s genetic signature, reducing the risk of rejection. In theory, the organ could be grafted into the patient with fewer compatibility issues. Yet experts caution that this work remains in the laboratory phase and faces technical and regulatory hurdles before it could become routine medical practice. One founder of a gene-editing company notes that the field is still several steps from clinical reality, even as the concept advances rapidly.

In parallel, surgeons in the field have begun to document more unusual but increasingly feasible procedures that hint at a broader future of replacements. In Georgia, a Georgian plastic surgeon reported a finger-to-penis reconstruction in which a patient’s middle finger was used to recreate penile structure after cancer-related amputation. The operation, which involved transferring tissue from the finger and reinforcing it with skin grafts from the underarm, aimed to reestablish both form and function. The patient was 60 at the time of the procedure, and his wife reportedly welcomed the outcome. While doctors noted that the absence of the glans may affect sensation or orgasm, some studies have suggested that erotic zones can develop on a reconstructed penis over time, with the potential for increasingly normal sensation. The procedure underscores a broader interest in using available body parts to restore function when traditional prosthetics or implants are insufficient.

Advances in prosthetics are expanding the capabilities of artificial limbs and other attachments for daily living and sport. One patient, a writer who underwent a leg amputation after a long struggle with a twisted limb, describes how modern prosthetics have evolved to support activities from rock climbing to surfing. The range of devices includes specialized attachments for gripping tools or sports equipment, blades designed for running, and modular setups that let wearers adapt their limbs for archery, table tennis, fishing, and even weightlifting. Musicians, too, can find prosthetic solutions that hold drumsticks or bows. The development of adaptive devices for tasks as precise as origami folding illustrates how broad the field’s ambitions have become, moving beyond mere walking to enabling a wide spectrum of skilled activities.

The quest to print organs and tissues—literally building them from a patient’s cells—continues to advance. At Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania, researchers are refining 3D bioprinting techniques that place living cells and extracellular matrix proteins in precise architectures. The goal is to replicate the structure and function of tissues, from patches that promote wound healing to entire organs. Of particular interest is the heart, where researchers are working to align cardiomyocytes in a helically organized arrangement that mimics the heart’s natural architecture. Early results have shown beating heart constructs that synchronize enough to pump in a coordinated fashion, representing a major milestone in tissue engineering. When a practical path to implanting fully functional bioprinted organs becomes possible remains a matter of timing and testing, but leading researchers project a decade-plus horizon for whole-organ implantation.

Temporary and durable skin substitutes are already reshaping burn care. At Massachusetts General Hospital’s burns unit, clinicians have employed xenografts—skin from another species—as temporary coverings to protect wounds and reduce infection while human skin regenerates. Icelandic cod skin grafts, in particular, have been used to decrease inflammation in burn patients, though doctors note that results vary with burn severity. The distinction between second- and third-degree burns remains consequential for outcomes, highlighting the careful clinical judgment required as new materials enter standard care.

Another frontier is hair generation from stem cells. Advances in induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells have opened the possibility of creating patient-specific cell types for a range of therapies, including hair follicle components. Since Shinya Yamanaka’s discovery in 2006 that adult cells can be reprogrammed to a pluripotent state, researchers have explored differentiating iPS cells into dermal papilla cells and keratinocytes—the building blocks of hair follicles. While experts stress that this is not about growing whole scalps or replacing entire heads, it could enable future therapies for baldness and perhaps broader regenerative strategies. Companies working in cell engineering envision a future in which a patient’s own iPS cells could be banked, providing a ready supply of cells for personalized therapies, much as people currently store genetic material or reproductive cells.

The range of work summarized here reflects a broader narrative in regenerative medicine: the body could become increasingly replaceable, not solely through transplantation of donor organs but through grown, engineered tissues, and even reimagined forms of bodily autonomy. The notes that guide this overview draw on research and reporting surrounding the book Replaceable You, which surveys the field and tracks multiple lines of inquiry—from xenotransplantation and organ bioprinting to advanced prosthetics and stem-cell therapy. The pace of development suggests that the coming years will bring clearer demonstrations of feasibility, regulatory pathways, and, ultimately, clinical protocols that could redefine the limits of what a patient can replace, reconstitute, or reimagine. Image:

Sources

- Daily Mail - Latest News - Organs grown inside your 'personal pig', and even a new penis made from a finger... How every part of your body could soon be REPLACEABLE

- Daily Mail - Home - Organs grown inside your 'personal pig', and even a new penis made from a finger... How every part of your body could soon be REPLACEABLE