Titan could harbor alien life in slushy tunnels, study finds

New analysis suggests Titan’s interior may be a mix of ice and meltwater, expanding possible habitats beyond a global ocean.

A reanalysis of data from NASA’s Cassini mission suggests Titan may host a slushy, partially melted interior rather than a global ocean beneath its frozen crust, according to a Nature study by researchers from NASA and the University of Washington. The team says a high‑pressure ice layer hosts meltwater pockets near a rocky core, a configuration that could provide nutrients and energy for simple life forms. The finding challenges the long‑standing view of a liquid, ocean‑world beneath Titan's surface and points instead to a more Arctic‑like regime.

Using updated data‑processing techniques, the researchers reassessed Cassini’s measurements of Titan's gravitational response to Saturn. They found that Titan’s shape‑shifting—its flexing in the planet's gravity—peaks about 15 hours after Saturn's strongest gravitational pull, a timing that helps quantify internal energy dissipation. The resulting dissipation would be much higher if Titan hosted a global ocean, supporting a layered interior with extensive slush.

The proposed model keeps most of Titan's exterior frozen but allows pockets of meltwater near the core. The authors say the slushy interior could supply concentrated nutrients and maintain warmth in localized regions, with some pockets reaching about 20°C (68°F)—a temperature range more compatible with known life processes on Earth. "Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we're probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers," said Baptiste Journaux of the University of Washington.

The study, published in Nature, broadens the range of environments scientists consider potentially habitable beyond Earth‑like oceans, and it could affect how researchers search for life on Titan and other icy worlds. The interior model implies that energy sources and nutrients might be accessible in localized zones rather than across a global ocean, which could influence how life, if present, might be distributed on Titan.

These findings come as NASA plans the Dragonfly mission to Titan, scheduled to launch in July 2028 and arrive in 2034. Dragonfly will be a rotorcraft lander designed to assess Titan’s surface composition, chemical processes, and habitability, building on decades of Cassini data. By examining diverse terrains and organic chemistry, Dragonfly aims to help scientists determine whether Titan’s environments could support life or prebiotic chemistry.

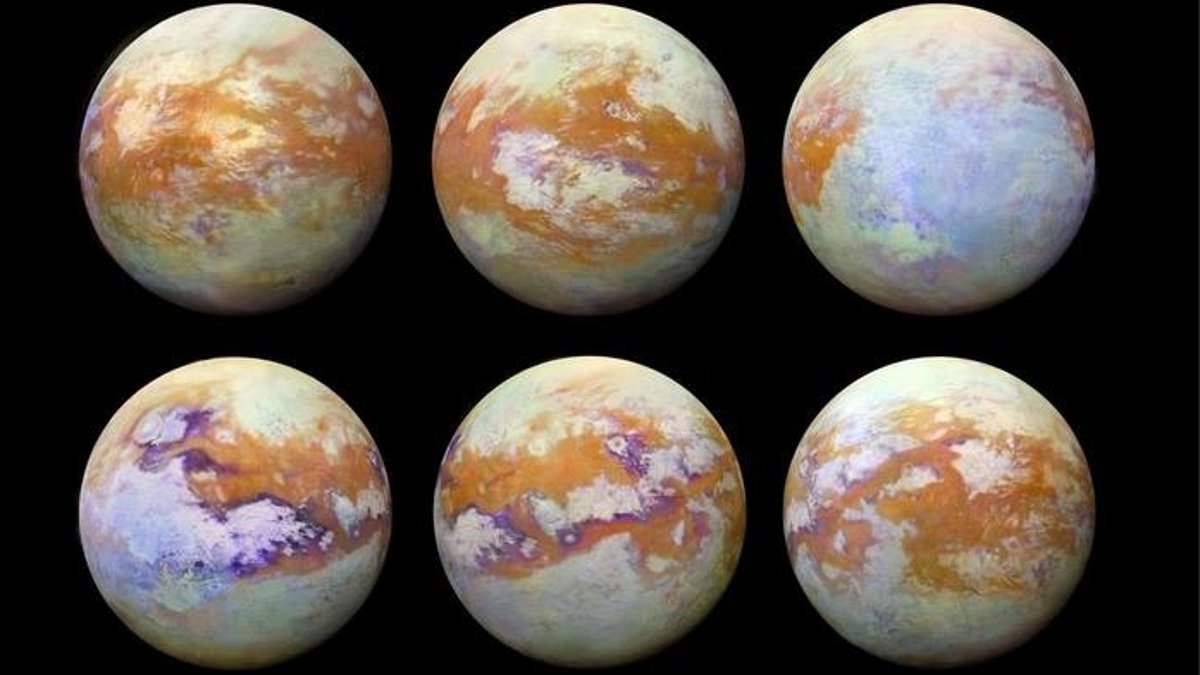

Cassini, launched in 1997, spent seven years en route to Saturn and more than 13 years studying the Saturnian system before its mission ended in 2017. The orbiter delivered the Huygens probe to Titan in 2004, uncovering methane and ethane lakes and a complex, hazy atmosphere. In the years since Cassini’s end, researchers have continued to mine its data for clues about Titan’s interior and surface processes, with the slushy‑layer hypothesis representing one of the most significant revisions to the moon’s potential habitability.

Several scientists say Titan remains a top target for astrobiology among icy worlds, alongside moons such as Enceladus and Europa. The new results are likely to shape the dialogue about where life might arise beyond Earth and which missions are best suited to test those ideas in the coming decades.