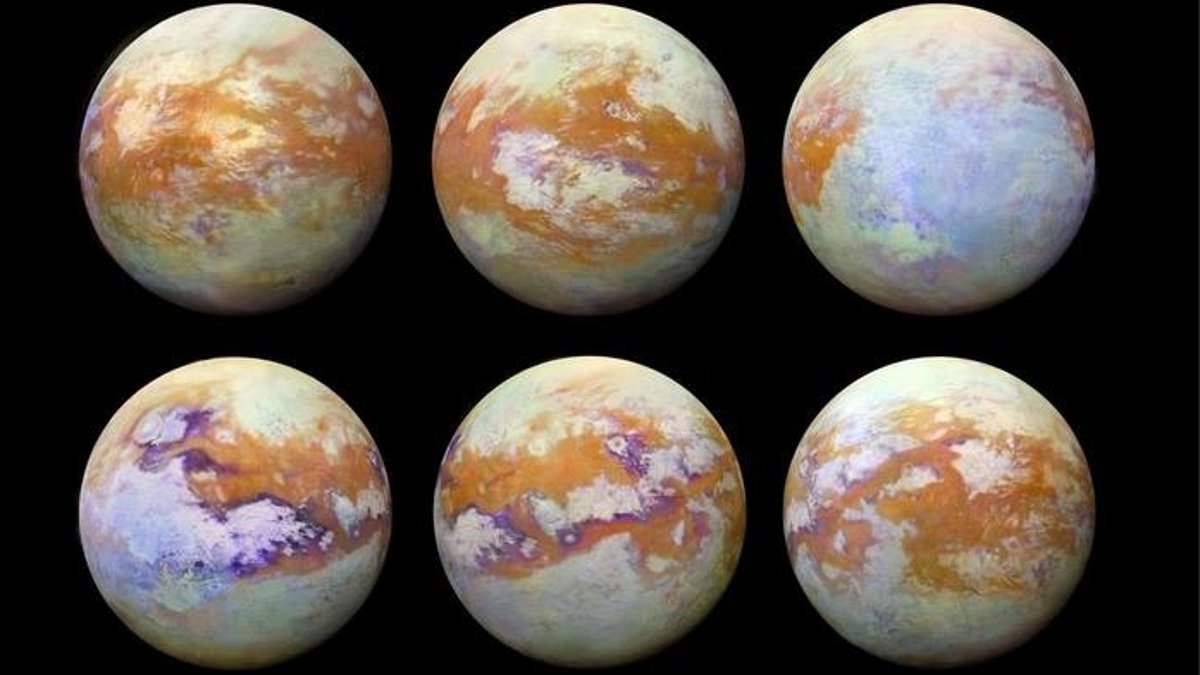

Titan's slushy interior could host life, study finds

Reanalysis of Cassini data suggests a high‑pressure ice layer beneath Titan's crust, not a global ocean, with implications for habitability and future missions.

A reanalysis of data from NASA’s Cassini mission suggests Saturn’s moon Titan harbors a slushy high‑pressure ice layer beneath its frozen crust that could support life in pockets rather than an open ocean. The finding, based on data from Cassini and analysis by researchers at NASA and the University of Washington, challenges the long‑standing view that Titan hides a global subsurface ocean. “Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we’re probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers,” said study author Baptiste Journaux of the University of Washington. “This has implications for what type of life we might find, the availability of nutrients, energy and so on.”

Titan, about 3,200 miles in diameter, is Saturn’s largest moon and, NASA notes, an icy world whose surface is hidden by a thick, hazy atmosphere. The team analyzed how Titan’s shape deformed as it orbited Saturn, using more than 15 hours of lag between Saturn’s gravitational pull and Titan’s flexing. The results indicate that the energy dissipated inside Titan is far stronger than would be expected if the moon had a global ocean, a “smoking gun” that the interior is different from previous inferences. The new model envisions more slush and less liquid water, with pockets of meltwater near a rocky core. In this scenario, Titan could host meltwater near the core at temperatures around 20°C (68°F), in confined pockets rather than an open sea. The lead author Flavio Petricca of NASA called the finding a significant shift from earlier analyses.

The discovery builds on Cassini’s decades of work at Saturn, including the Huygens probe’s 2005 landing on Titan and later observations of methane‑ethane lakes that hint at a methane‑water cycle on the surface. Researchers say the slushy interior would still expose a habitable niche if nutrients and energy sources are concentrated in small volumes of water near the rocky core. The possibility of life in subsurface brine or slushy pockets expands the range of environments considered potentially habitable beyond a planetary ocean.

The study, published in Nature, underscores Titan’s continuing value for astrobiology. It suggests that future missions could target both surface and near‑surface processes to understand how life could thrive in slushy environments. NASA’s Dragonfly rotorcraft lander, planned to launch in July 2028 and reach Titan around 2034, is designed to study Titan’s chemistry and habitability up close, potentially testing how nutrients and energy might behave in a slushy interior. Scientists say Dragonfly’s findings, combined with Cassini data, could sharpen our understanding of how life might arise on worlds with icy crusts and subsurface ice layers.

“Titan’s deformation pattern is a crucial clue to what lies beneath,” said Journaux. “The data support a more complex interior than a single ocean, which opens new possibilities for habitability.” The study’s authors note that while a global ocean remains a potential explanation in some contexts, the presence of slushy high‑pressure ice and meltwater pockets would still provide energy gradients and nutrient pathways that life as we know it could exploit. The discovery is part of a broader shift in planetary science toward recognizing diverse, layered interiors on icy moons.

Cassini launched in 1997 and spent nearly two decades studying Saturn and its moons before concluding its mission in 2017 with a controlled plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere. Its data archive continues to yield insights as researchers apply new techniques to older measurements. In 2019, Cassini data confirmed methane lakes on Titan are hundreds of feet deep, underscoring the moon’s exotic chemistry and the potential for life‑friendly niches beneath its surface. With Dragonfly approaching, scientists anticipate new discoveries that could either bolster or refine the slushy‑interior hypothesis.